A monumental difference: More reflections on W. Eugene Smith

One morning last week I sat down at the breakfast table and Judith greeted me with: “Wait till you hear this!” She proceeded to read me the first sentence from a blog posting she’d just come across. The author Daniel Milnor a documentary photographer living in the Southwest bemoaned

“I somehow managed to graduate from photojournalism school without ever hearing of one W. Eugene Smith.”

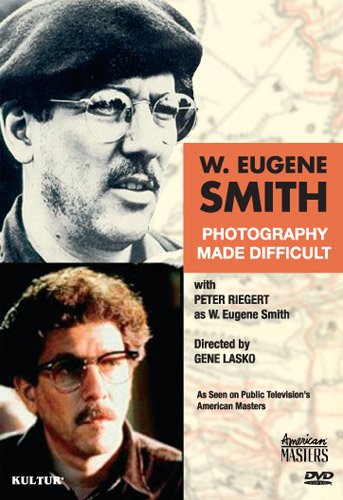

Milnor is a great story-teller and he proceeds to describe how he came across a DVD on Smith’s life in a box holding up his TV while he was sick in bed from a malady his doctor had just warned was life threatening. He claimed the DVD changed his life. Of course my first thought was: “How is it possible that someone could get through photojournalism school without hearing about Gene Smith, one of the great geniuses of the form?” And then I thought again. How appropriate that the man who was frequently ridiculed and derided by editors and even some photographers was once again overlooked by a field that he did so much to define. This is something like wandering in the foothills of photography and never noticing the mountain.

Milnor is a great story-teller and he proceeds to describe how he came across a DVD on Smith’s life in a box holding up his TV while he was sick in bed from a malady his doctor had just warned was life threatening. He claimed the DVD changed his life. Of course my first thought was: “How is it possible that someone could get through photojournalism school without hearing about Gene Smith, one of the great geniuses of the form?” And then I thought again. How appropriate that the man who was frequently ridiculed and derided by editors and even some photographers was once again overlooked by a field that he did so much to define. This is something like wandering in the foothills of photography and never noticing the mountain.

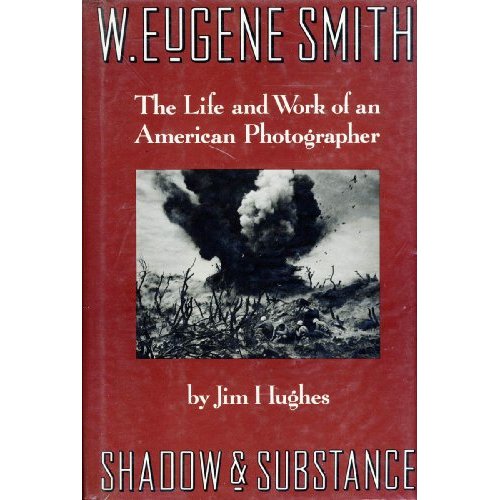

I wrote a comment on Milnor’s blog (called Smogranch) and it sparked a conversation between us that will continue next summer when he and his wife come for a visit. I’m looking forward to that. He titles his blogpost W. Eugene Smith:Photography Made Difficult taken from the PBS American Masters film of the same name produced in 1989, the same year McGraw Hill released Jim Hughes’ definitive biography W. Eugene Smith:Shadow and Substance.

I knew Hughes through my own work with the now defunct Camera Arts magazine. To refresh my memory on some of my own conversations with Hughes for the book (which weighs in at an impressive 606 pages!) I pulled it off my shelf and purused it. It’s a good read for those interested in a very in-depth biography of a great man. Here are a few threads of my own story of knowing and loving the man.

Gene and I met in 1949 when I was just 18 and he was 30. I had already generated a large and pretty impressive portfolio of my home turf Coney Island, which I began photographing in 1946 when I was 15. I had been going around to various photographers showing my work and it was Arnold Newman the great portrait photographer who I knew from the Photo League who suggested I pay Gene a visit. I went up to see him at his apartment on 74th Street. As Hughes put it: “Gene took an immediate liking to the pudgy, bespectacled youngster with the straight-on style; not only did Harold know how to make good black-and-white prints, but he had already mastered the fine art of ferricyanide bleaching.” (I shared about this in another post “Reminiscences of W. Eugene Smith, 1955)

Gene and I met in 1949 when I was just 18 and he was 30. I had already generated a large and pretty impressive portfolio of my home turf Coney Island, which I began photographing in 1946 when I was 15. I had been going around to various photographers showing my work and it was Arnold Newman the great portrait photographer who I knew from the Photo League who suggested I pay Gene a visit. I went up to see him at his apartment on 74th Street. As Hughes put it: “Gene took an immediate liking to the pudgy, bespectacled youngster with the straight-on style; not only did Harold know how to make good black-and-white prints, but he had already mastered the fine art of ferricyanide bleaching.” (I shared about this in another post “Reminiscences of W. Eugene Smith, 1955)

Gene was heading off to Spain when we met to begin his Spanish Village project, but we picked up our friendship when he returned several months later. During the ensuing years I was witness to the many derogatory comments about Gene from editors and other photographers because of his driven, passionate approach to his work, which admittedly did result in some chaos around him and a proclivity to extend deadlines and produce much more that anticipated. He was known as “crazy” Gene. Great but crazy. From my perspective it was the small minded editors and standard bearers of photography protocol who simply couldn’t appreciate Gene’s greatness. Thus his foibles became the stuff of gossip mills and his real greatness often got lost in the endless critique of his personality and idiosyncracies.

In spite of his ornery manner with editors, he was a generous and kind friend. I remember when I was switching cameras from a Rollieflex to 35mm and my camera had broken. I was using a borrowed Contax. One day we were driving down Seventh Ave and he made a stop at Minifilm, his camera store at the time, and brought me inside. He had me pick out a Leica and put it on his charge account. At the time new Leica’s were hard to get and most people used second-hand ones. On the spur of the moment he bought me a brand new $300 Leica.

Another time he came to Brooklyn to meet my fiancé and when we married he gave us one of his best prints of the Spinner from Spain. Decades later I would lose that print when my girlfriend at the time couldn’t remember where she parked my car somewhere in Manhattan – with many valuable posessions in it, including cameras. But that print was the greatest casualty. The car was never found and I certainly hope whoever got it in the end could appreciate what they got!

I liked to joke that Gene always followed in my footsteps! Such as the time he moved into my loft at 821 6th Ave. As one of the original four loft dwellers at the time, I shared a floor with jazz composer Hall Overton, who did arrangements for the great jazz musicians of the time, including Thelonius Monk. David Young, a painter and filmmaker had rented three floors of the loft – formerly a brothel – for $120 and then sub-leased two floors at $40 a piece, something I was just able to afford. Dick Carey, the jazz trumpeter lived below me and over time many jazz giants made their way to the loft for all night jam sessions. I lived at the jazz loft from 1954 – 1957, up until the birth of my first child Robin, when it became clear that the necessities of a baby would not be well served in the loft. So Gene moved in to my place. Between 1957 and 1965 he would take 40,000 photographs and 4,000 hours of audio tape documenting the jazz scene inside the loft – a feat memorialized in Sam Stephenson’s book and exhibition “The Jazz Loft Project”.

Now, I had enjoyed taking occasional photographs from the windows of the loft, but Gene made the spot famous with his own series called From my Window. So as he was getting ready to make his next move – this time to take over my space on 747 6th Avenue, I wrote on the window in large lettering “copyright Harold Feinstein”! The fun wasn’t lost on him.

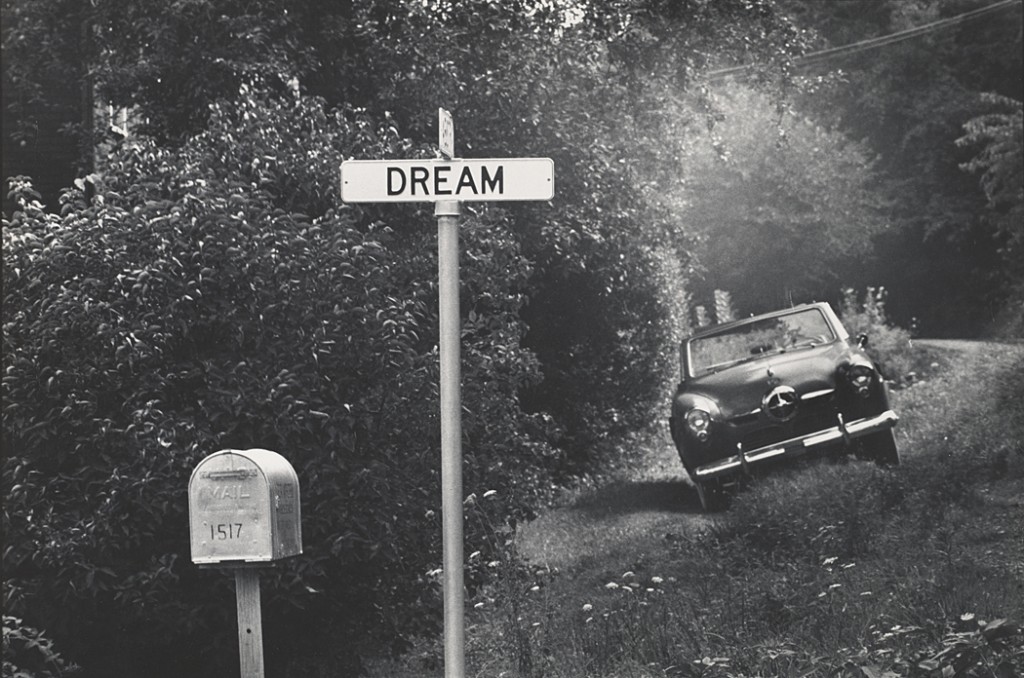

In 1958 Gene asked me to help him organize, edit and lay-out photographs from his Pittsburgh Project photo essay. A three week assignment that turned into 3 years and 17,000 photographs. Gene considered it his masterwork and was always disappointed that more of it was not published. Origianlly commissioned by photojournalist Stefan Lorant to accompany a book on Pittsburgh’s bicentennial, Gene would move there and become completely absorbed in the dynamism of America’s most industrial city. His dedication — some might say obsession — resulted in a massive body of work. In the process he missed a number of publishing opportunities as the time passed. Finally a 37 page spread was published in the 1959 Popular Photography Annual. For a film about the Pittsburgh Project see Brilliant Fever produced by Kenneth Love, Barbara McNulty, Henry Shapiro, and Sam Stephenson. For more see the book by Alan Trachtenberg Dream Street published in 2003.

As much as Gene cared deeply about a great photograph, his ultimate desire was to change the world, and he did that in many ways. In 2007 I had a visit from Sam Stephenson while he was researching the Jazz Loft book. He asked me to share my memories of Gene and you can hear more of them here.

“He was a great photographer totally devoted to his art and a ground-breaker in the realm of photojournalism. As a photographer he was highly evolved, highly principled. [Many people who ridiculed him] just couldn’t relate to the essence of greatness. Without any question in my mind he is a monumental figure. Not only as a photographer — but he did projects in order to make changes in the world. He got involved in things to make a change in the lives of people. He wanted to make a difference. And he did – a monumental difference.”

Another fascinating glimpse into the world of photography that you had the privilege of being immersed in! Thanks, Harold, for continuing to improve my photographic eye through this blog! Looking forward to seeing you and Judith when we come back in May!

Best, Allan (& Barbara)

Can’t wait to see both of you! At 82, there is so much to reflect on. I’m glad you’re enjoying my ramblings!