A love affair with teaching: “It’s like seeing the summer again after a long winter”

At long last, and with the help of my good friend and renaissance man, Jason Novak, I am making a small dent in reviewing, editing and packaging the huge volume of audio-visual materials that provide an inspiring record of Harold’s 56 years of teaching. I have over 20 hours of video and 100 hours of audio, plus boxes of written materials. Enough to keep us busy for a very long time! The initial offerings consist of clips between 1-3 minutes for social media postings, and the roll-out on those has been underway for about a month. You can check them out on YouTube or on our Facebook, Instagram or Twitter feeds (@haroldfeinstein).

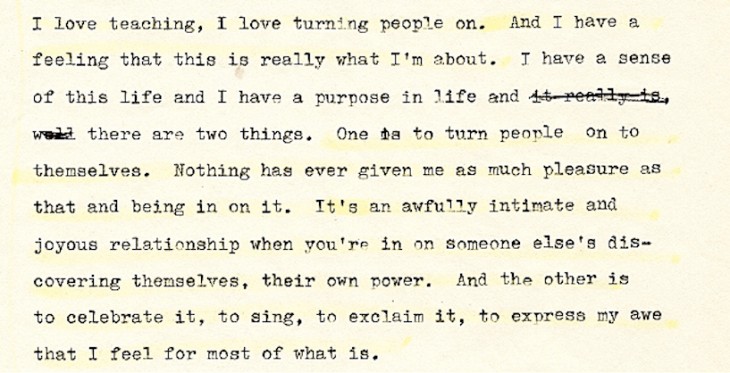

Teaching was a passion for Harold. He considered it as important as his art and it would be impossible to get a true picture of the man and his legacy without looking deeply at his role and influence as a teacher.

As someone who never graduated from high school yet received teaching fellowships for graduate level courses, he provided a level of inspiration for his students that has stayed with most of them to this day. And it was his dedication and love of teaching that drew his attention away from the more linear path toward personal recognition for his art, which was really beginning to blossom by the time he began teaching.

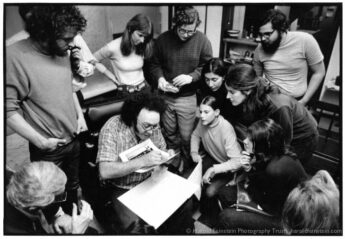

Feinstein became one of a small handful of master teachers whose legendary private workshops and art-institute classes — which he taught regularly for more than forty years — proved instrumental in shaping the vision of hundreds of aspiring photographers. Like many who teach, both inside and outside the academic setting, he often set career concerns aside to concentrate his attention on his students’ needs.

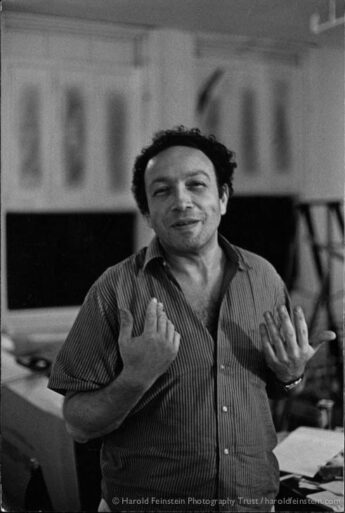

Harold began teaching in New York in 1957 at the age of 26 and his workshops soon became legendary. In those early years his students included Ken Heyman and also Lou Draper and Herb Randall, two founders of the Kamoigne Workshop, a collective of African American photographers centered in Harlem.

Over the course of five decades, he had stints at numerous other institutions including the Maryland Art Institute, the School for Visual Arts, UMass Amherst, Windham College, and Holy Cross College, but it was his private workshops run from his own studio that were the most consistent offerings over the years. Others who credit their foundational direction to Harold include Wendy Watriss (co-founder of Houston FotoFest), Bob Shamis (formerly curator at the Museum of the City of New York), and photographers Carole Gallagher and Lori Grinker, among others.

And even as he kept a low profile personally, his workshops were being promoted by others in the art establishment. In an earlier blog post, he shared the shock and pleasure he felt upon hearing from a former student that John Szarkowski, the head of the photography department at MOMA, was recommending Harold’s classes to students eager to learn street photography. (While Harold had had a friendly relationship with Edward Steichen, he had not really gotten to know Szarkowski who took over from Steichen in 1962 when Harold was living in Philadelphia. See the post: Belated thanks to John Szarkowski: Reflections on the joy of teaching).

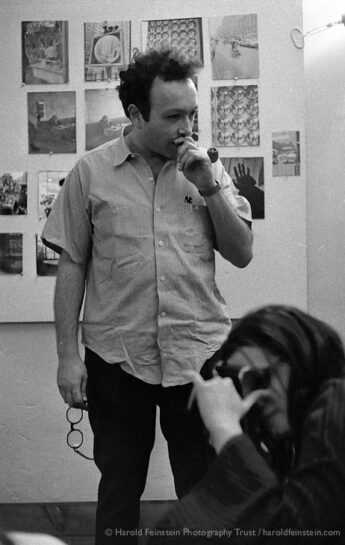

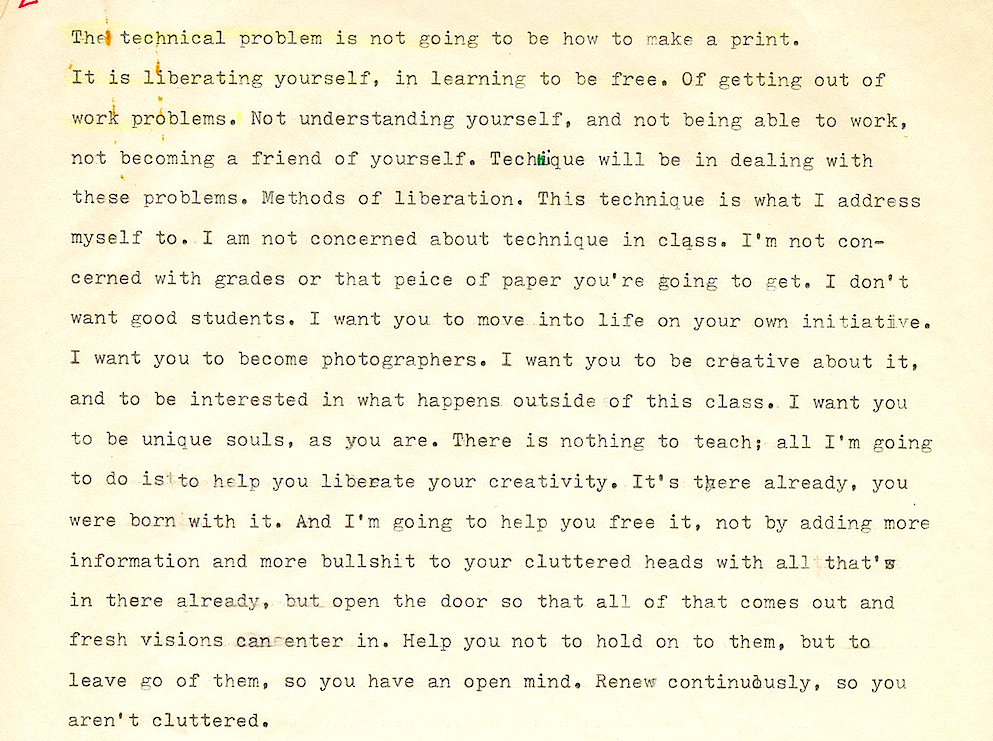

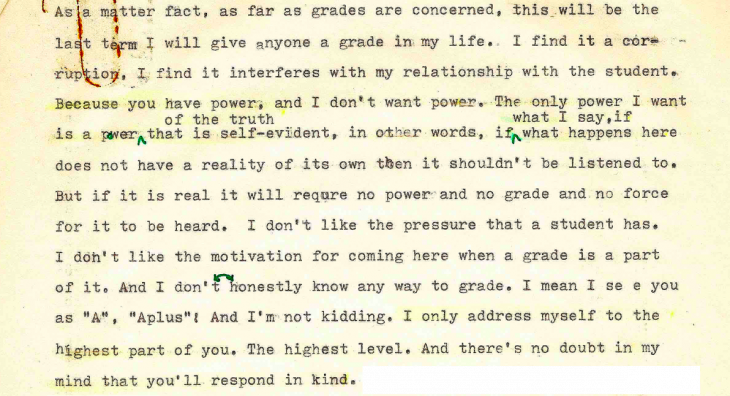

Harold’s teaching style was untraditional–focusing less on technique and more on the liberation of personal vision. To that end he was an enthusiastic appreciator and encourager of each student’s innate creativity.

When working in institutions he fought against the grading system believing that students should come freely to learn out of joy and not out of competition or pressure.

The impact of his teaching can be heard in these words from a few of his former students.

It was a workshop with Harold in the early 1970s that put me on the path to a life in photography, and I am sure that this is true for many other students of his. Harold taught about photography not as a career path, but as an integral part of one’s life that called for commitment, dedication, and a love of the medium. And he always spoke about the joy of it. Without that joy, photography simply wasn’t worth pursuing. Bob Shamis, former curator of prints and photographs, Museum of the City of New York

Harold’s workshops were a kind of baptism for most of us. I have never had a teacher who was more alive, more capable of keeping his dream of creation potent and viable. It was in his class that I realized the fallacy of “the rules” of the art world which had been beaten into me by the relatively unsophisticated and clearly cynical teachers who proceeded him. As I went through the motions of success in the quarter century afterward, I can measure my own failures only by keeping in mind all those times when the memory of his instruction may have been forgotten in the pursuit of what is less valuable in an artistic life: the connections, the self-promotion, the ruthlessly self-serving nature of careerism, all of which have nothing to do with the power and authority of one’s own intuitive aesthetics. If one listens attentively to Harold and remembers even a part of his wisdom, the reward is the courage to create and be fulfilled by that creation. It is, after all, our work and our gratitude for the gift of creativity which truly gives us life. Carole Gallagher, American Ground Zero.

Studying with Harold was the foundation for me. Everything grew from that. He encouraged me to find my own voice in photography. I put people in certain categories. In my humble opinion, I’ve met a lot of people and I thought I knew a lot of stuff. But Harold was from somewhere else. If anybody asked me if I ever meet anyone who I didn’t believe to be human — my first thought would be of Harold. I mean that in a positive sense — a very wonderful way. In fact, he may have been the only human and the rest of us weren’t. But he was from somewhere else. Herbert Randall, co-founder, The Kamoinge Workshop, photographer for Freedom Summer

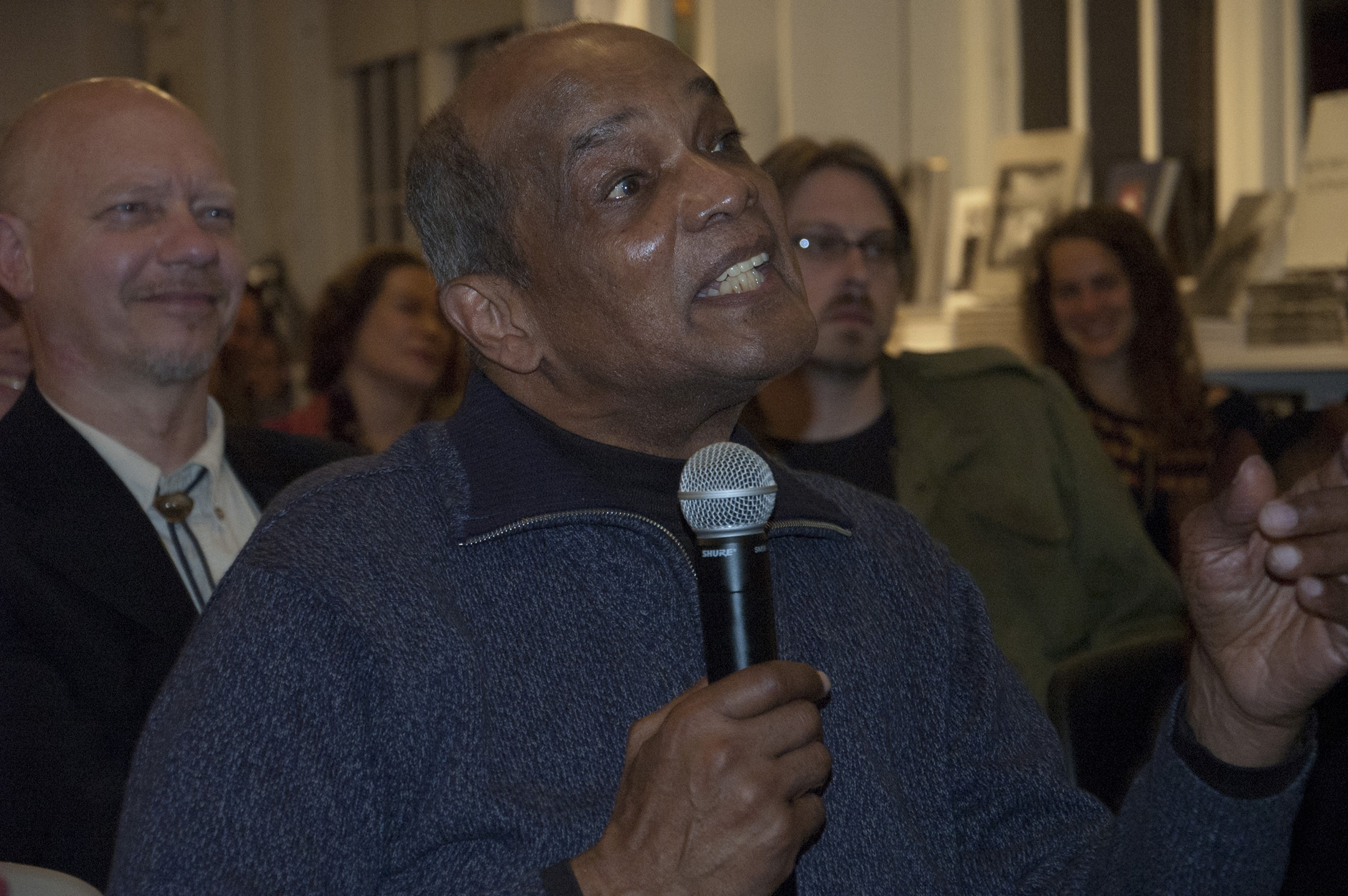

For Harold, each class was an opportunity to probe not just photography, but all aspects of the creative process as it intersects with our daily lives. His own deep gratitude for beauty and for life itself came through in his classes…as it does in this brief video clip below. Enjoy.