The Jazz Loft, The Limelight, The friendship: Harold Feinstein and W. Eugene Smith

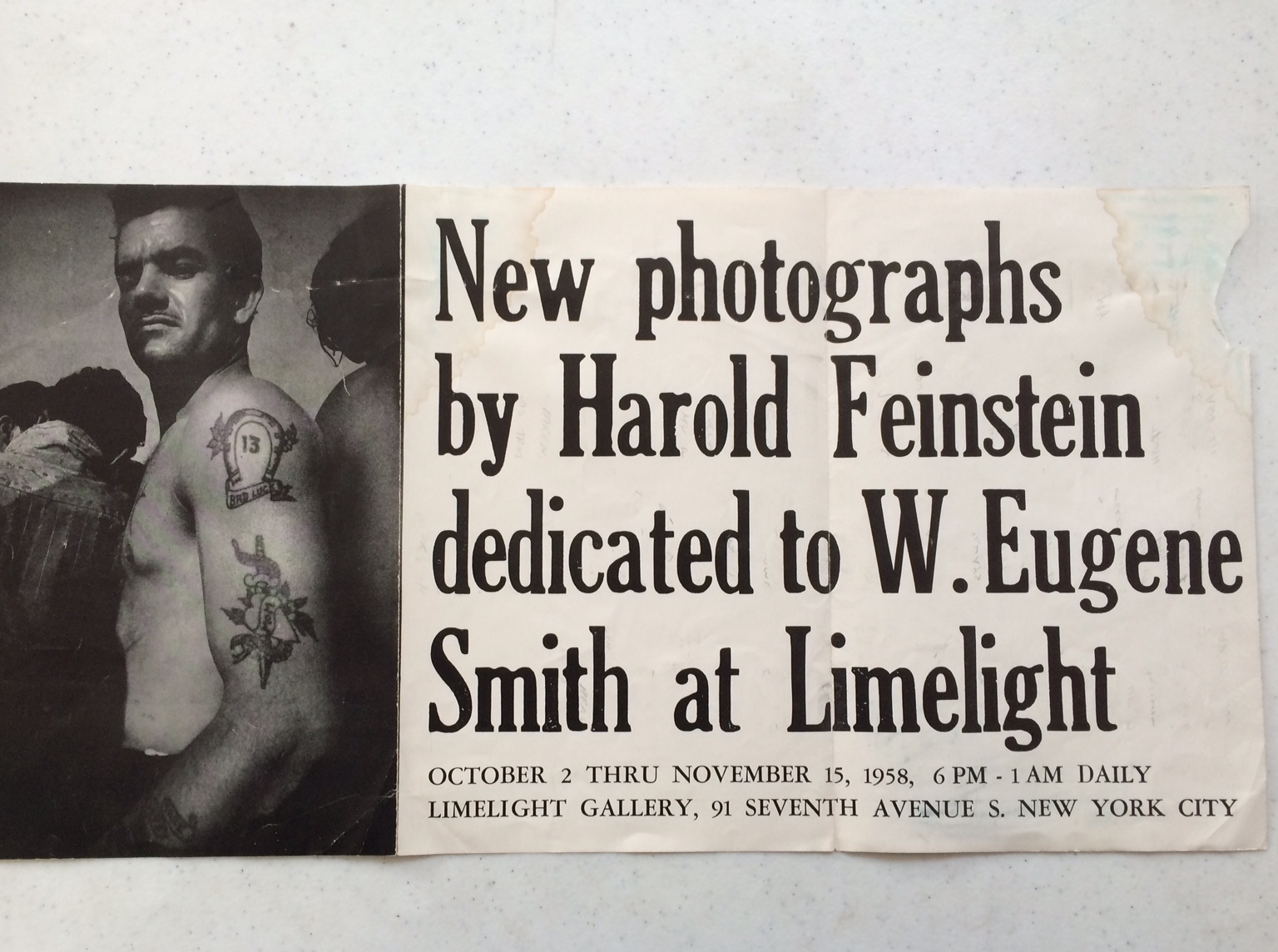

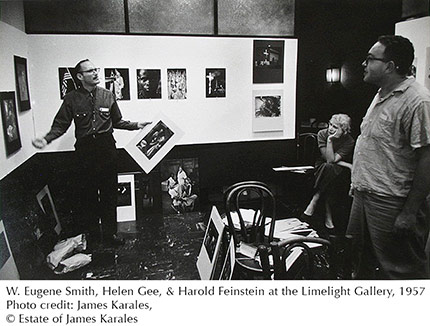

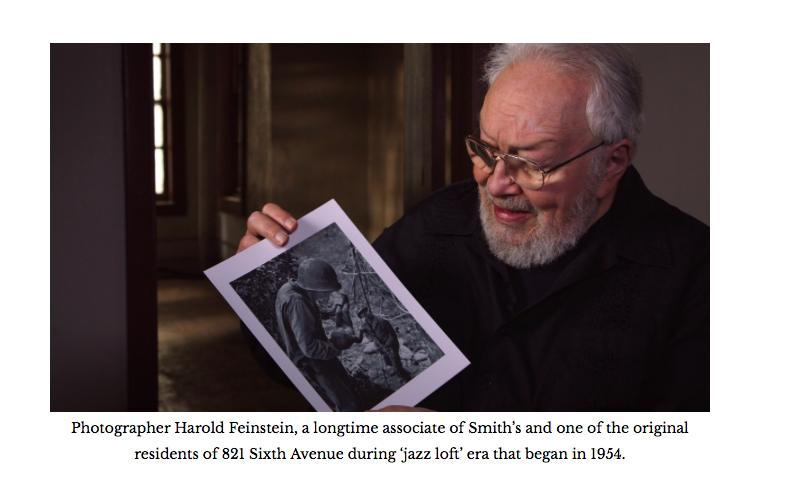

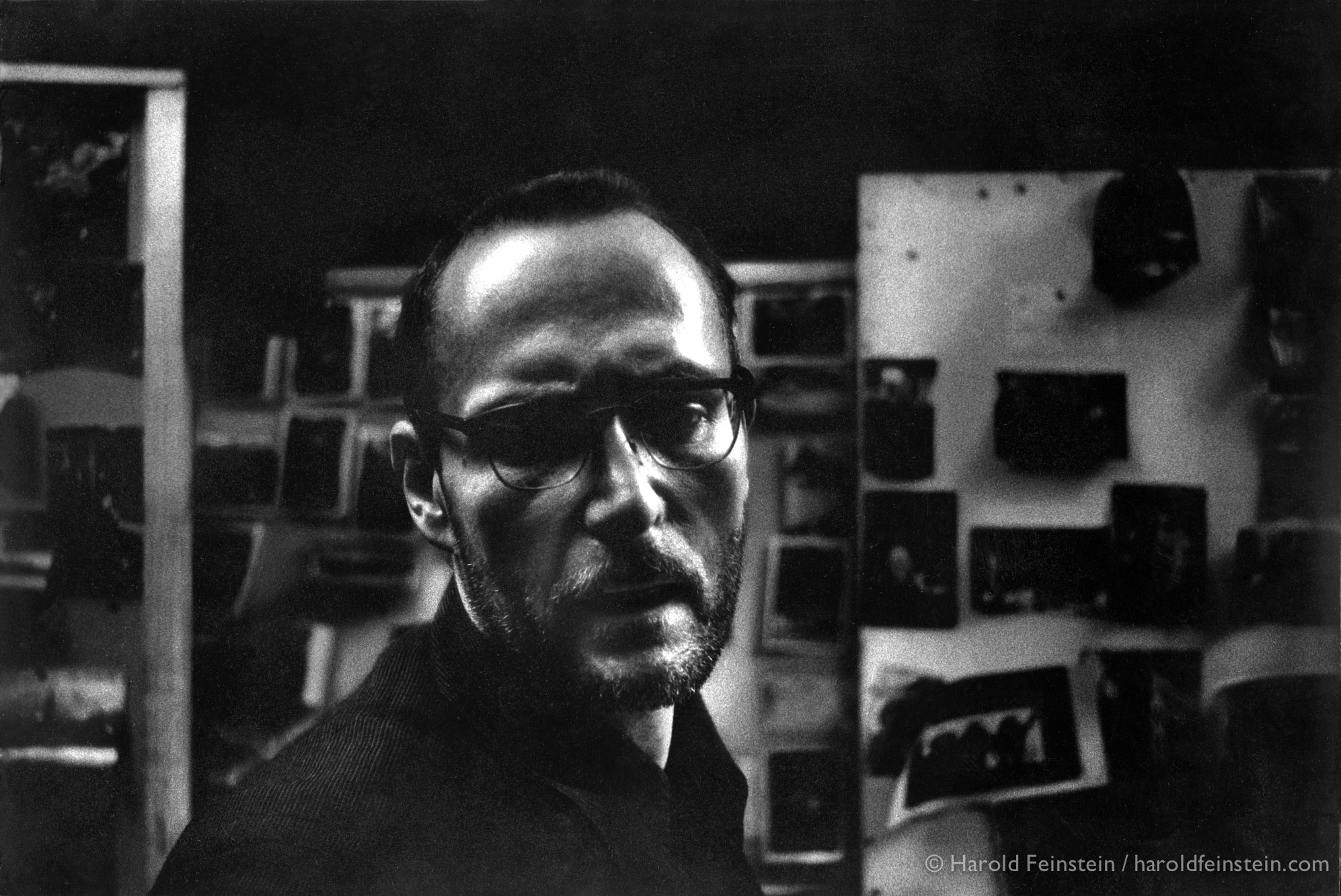

It would be a year later that Harold’s Limelight show went up dedicated to Smith. In the intervening time between those two shows, Harold, who had been living at the Jazz Loft at 821 Sixth Avenue for three years, moved out with his partner, jazz pianist Dorrie Glenn, who was pregnant with their first child. Smith, whose own marriage was crumbling, moved into Harold’s space in the loft and proceeded to wire it up for sound and photograph jazz sessions. The result was over 40,000 negatives and 4,000 hours of audio recording, which were only discovered in the 1990s.

Spring 1957: Last night dinner at Harold Feinstein’s. A long loft room, all across one floor, floor uneven and with holes. Harold tall and roundfaced, showing his work. His wife pale and blond, pregnant. In the front of the room all his photographic equipment. In the middle of the room, a double bed. In the back a stove, a table, an icebox. The dispossessed life of the bohemians I knew in Paris. The talk was rich. On the floor above him, live jazz musicians.

In 1998 David X Young told Jazz Loft Project director Sam Stephenson his own recollections of the early days of the loft scene. His description points to why Harold and Dorrie decided they had to move with the birth of their daughter, Robin. Having plumbing and a toilet would be a necessity!

The place was desolate, really awful. The buildings on both sides were vacant. There were mice, rats, and cockroaches all over the place. You had to keep cats around to fend them off. Conditions were beyond miserable. No plumbing, no heat, no toilet, no nothing. My grandfather loaned me three hundred dollars and showed me how to wire and pipe the place.

Harold wrote several blog posts about his friendship with Smith over the years and links are below. He was introduced to Smith in 1949 by Arnold Newman who Harold had come to know through the Photo League. The relationship would become one of the most important in his life. From the Stephenson interview:

“I met Gene when I was looking for a job as an assistant, and I’d gone to see Arnold Newman. And he was very interested in my work, but he said ‘You know, this is not the place for you. You should go see Gene. He’s crazy, but he’s great.’ And I went to see Gene and he really loved the work a lot and he said: ‘You don’t want to be an assistant’. And we just became friends. I was 18 or 19 when I met him and he was in his early 30’s.”

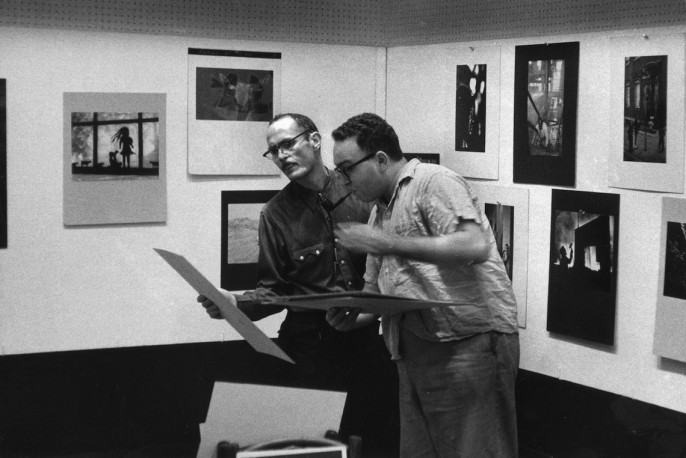

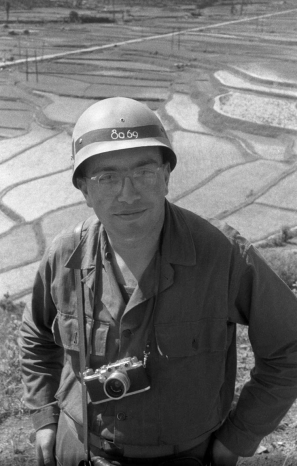

Shortly after they met Harold began to help Smith to edit and do lay-outs for publications. In 1951, right before Harold was drafted, Smith bought him a Leica which he took with him to Korea and used for all his photographing during that time. Harold told the story this way:

“[H]e was a generous and kind friend. I remember when I was switching cameras from a Rollieflex to 35mm and my camera had broken. I was using a borrowed Contax. One day we were driving down Seventh Ave and he made a stop at Minifilm, his camera store at the time, and brought me inside. He had me pick out a Leica and put it on his charge account. At the time new Leica’s were hard to get and most people used second-hand ones. On the spur of the moment he bought me a brand new $300 Leica.

In 1960, several years after moving out of the Jazz Loft, Harold moved to Philadelphia with a teaching fellowship at the Annenberg School for Communications. He stayed there for several years. He and Smith stayed in close touch until Smith death in 1978. Smith’s personal and professional life were the frequent subject of ridicule. He burned many bridges and had a reputation for being obsessive and imperious. But Harold’s admiration for him as a friend and photographer can be found in his interview with Sam Stephenson:

“He was a great photographer totally devoted to his art and a ground-breaker in the realm of photojournalism. As a photographer he was highly evolved, highly principled. [Many people who ridiculed him] just couldn’t relate to the essence of greatness. Without any question in my mind he is a monumental figure. Not only as a photographer — but he did projects in order to make changes in the world. He got involved in things to make a change in the lives of people. He wanted to make a difference. And he did – a monumental difference.”

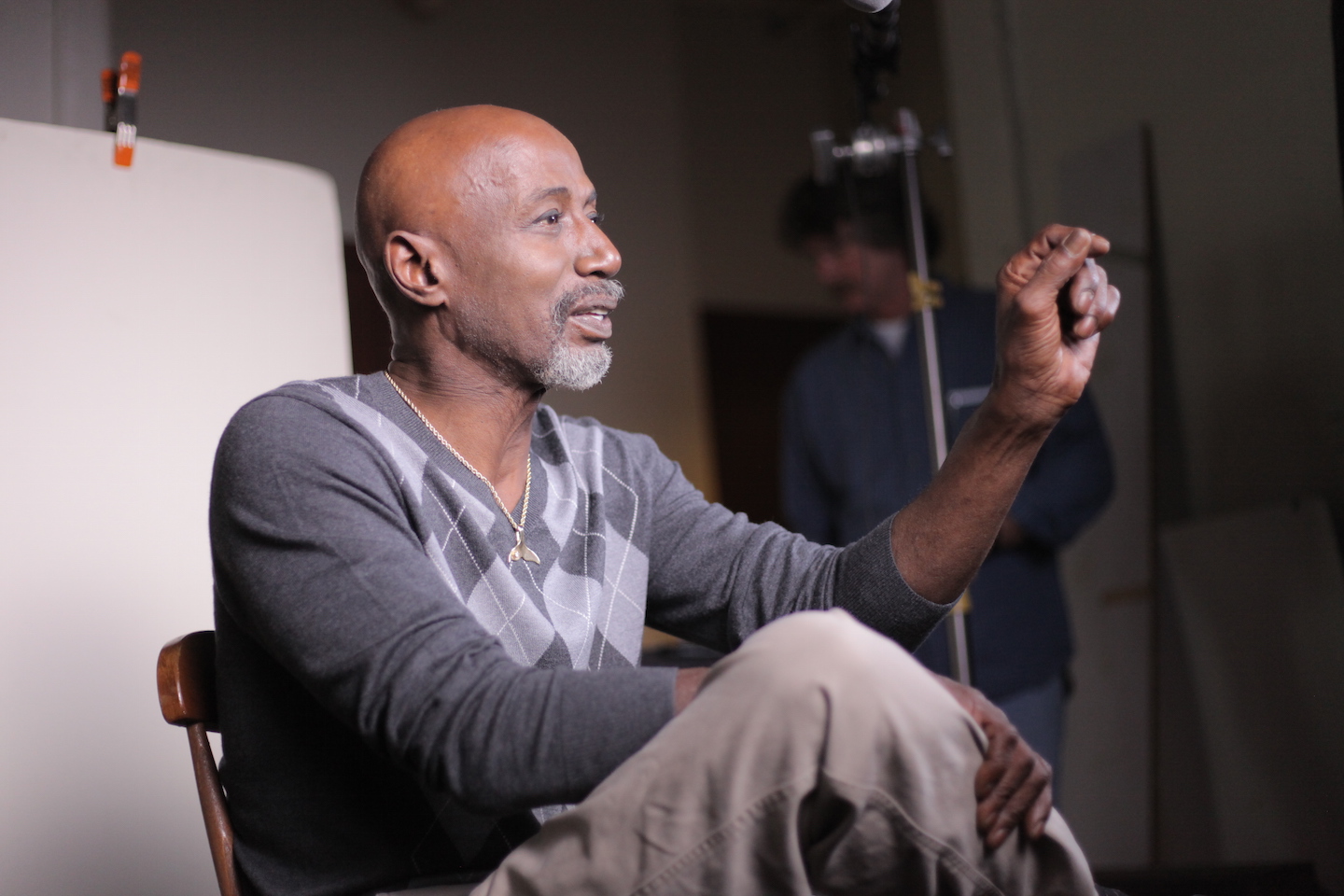

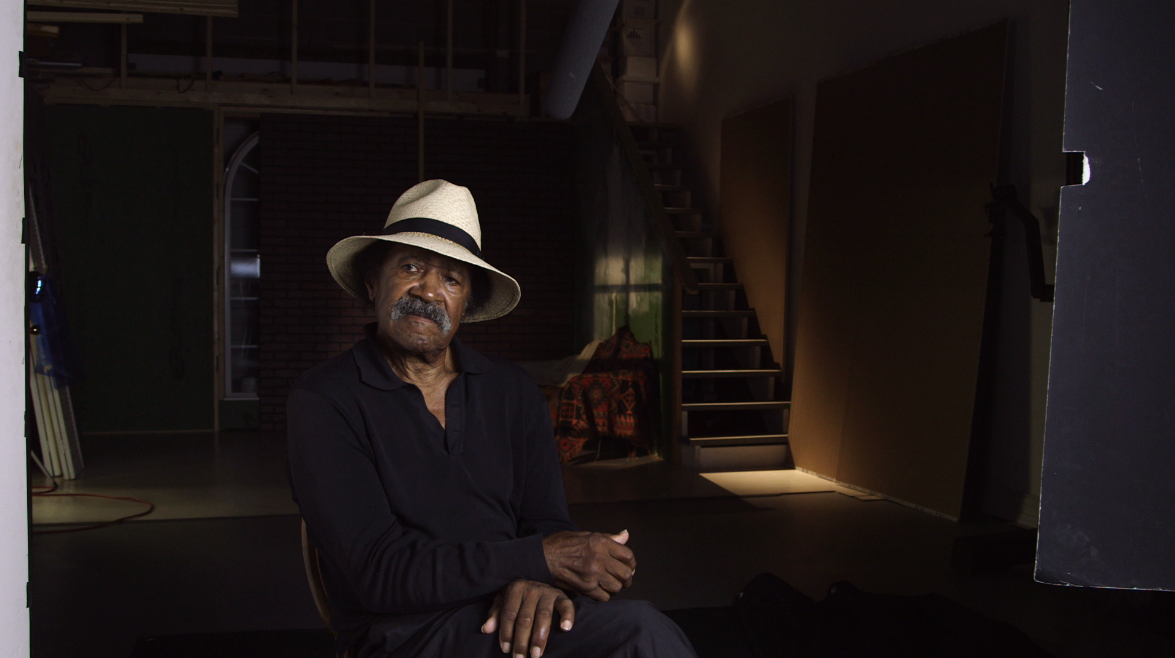

Note: Tom Hurwitz’s photographs are screen captures from the documentary and can be seen at Stephenson’s website Rockfish Stew.