Harold’s students: Louis Draper, Herbert Randall and the Kamoinge Workshop

In 1963 a group of African American photographers, mostly based in Harlem, came together to form the Kamoinge Workshop. The name comes from a word in the Kikuyu language of Kenya meaning “a group of people acting together”. It’s purpose was to reflect the truth about the world and themselves and to provide a supportive and nurturing forum for their exploration of photography as a means of expression. Now, a new book has come out,Timeless:Photographs by Kamoinge, (Schiffer, 2015) and at last some shows of Kamoinge members — past and present — are beginning to bring the contributions of the group to the public.

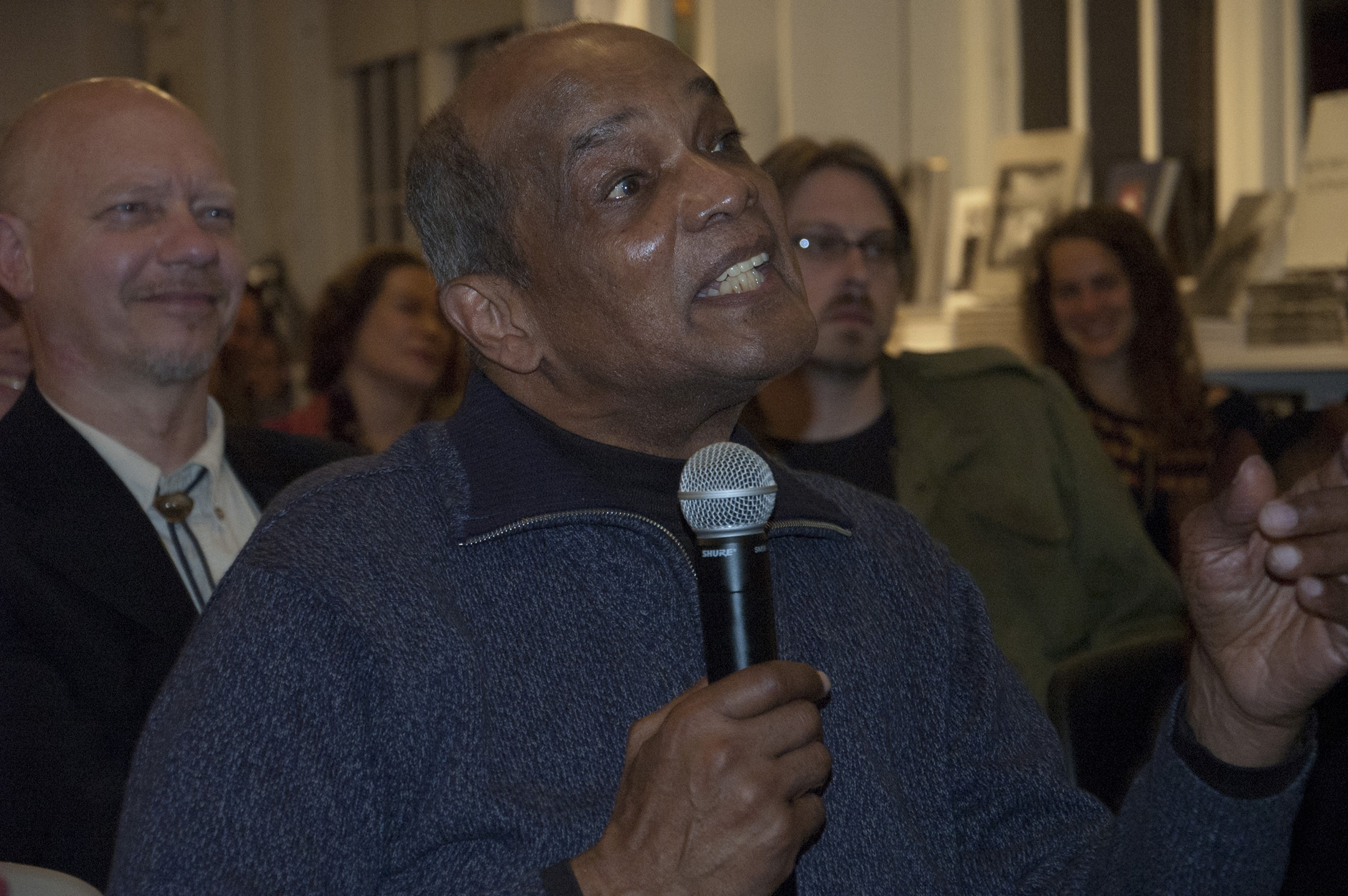

I had never heard of Kamoinge until several years ago when a friend of mine sent me a few scanned pages from a book entitled The Self in Black and White: Race and Subjectivity in Postwar American Photography by art historian Erina Duganne. The passages she sent highlighted Harold’s role as a teacher of Louis Draper, one of the founding members of Kamoinge. I later purchased the book, which I recommend to anyone interested in race and visual culture, particularly during the Civil Rights era. Another one of the original founders, Herbert Randall, was also a student of Harold’s. He came to see him in New York in 2012 at the Aperture book signing party. The two hadn’t seen each other in over 50 years and it was a moving reunion.

In the spring of 2014 Harold launched “Spotlight on my students” — a new category of posts for his blog. It is a way to showcase his student’s work, share their words and his own. Due to his failing health only the first post in that series got completed (see: The empathic eye of Mariette Pathy Allen). However, a number of others have remained in a draft file for future completion including some of his recollections of Louis Draper and Herbert Randall. When I got the recent New York Times Lens Blog “Half Century of African American Photography” in my in-box last week announcing the release of the book, it seemed like the right time to complete what Harold had started. I was fortunately able to get Herbert Randall, now 79, on the phone for a brief interview as well. Lou Draper passed away in 2002.

To begin my interview of Harold I read him the scanned pages I’d been sent and asked him to comment. I’ve included here a brief excerpt of the quotes from the book.

Louis Draper had been taking courses at the New York Institute of Photography and was dissatisfied with the guidance he was receiving there.

“Draper quickly switched into an independent photography workshop by Harold Feinstein. As part of this workshop Feinstein encouraged students to photograph subjects with whom they felt a deep emotional affinity. [Feinstein] explains,

‘Where do I go to photograph? This important question is asked me by And I tell them, you must photograph where you are involved; where you are overwhelmed by what you see before you; where you hold your breath while releasing the shutter, not because you are afraid of jarring the camera, but because you are seeing with your guts wide open to the sweet pain of an image that is part of your life.’

The emphasis that Feinstein placed on ‘photographing where you are involved’ as well as the prominence he gave to technical skills became foundational in Draper’s development as a photographer.” (p. 41)

Harold also brought W. Eugene Smith in as a guest teacher and Lou later studied with him as well.

“To their credit, both Gene and Harold were very sympathetic. I did not shy away from bringing black work to either of them because they both believed that one should photograph where your emotions are and that is something I know about. I didn’t know about Wall Street.” (p. 42)

From my interview with Harold August 5, 2014.

Judith: What do you remember about Louis Draper and Herb Randall, who were both founders of the Kamoinge Workshop? And what is your thought about the quote I just read?

Harold: Well, I would stand by that quote today. I always encourage students to photograph from their own lives; to respond to where the emotion is. What grabs you? What calls you? Bearing witness to our lives is what it’s all about as far as I’m concerned. Or just bearing witness period. But whatever makes your drop mouth open is going to be informed by your own background, your emotions, and sensibilities, not the dictates of the art world or any other “shoulds.” I don’t think I ever thought of Lou or Herb’s work as “black” work. I can’t imagine thinking that. For me, it was always are you bringing in work? Are you photographing a lot? I’m glad I could be supportive in turning anyone on to their vision and helping them to move toward it. The key is taking a lot of pictures! Not talking about technique or starting in any real linear fashion around technical stuff, but getting out there and taking lots and lots of pictures.

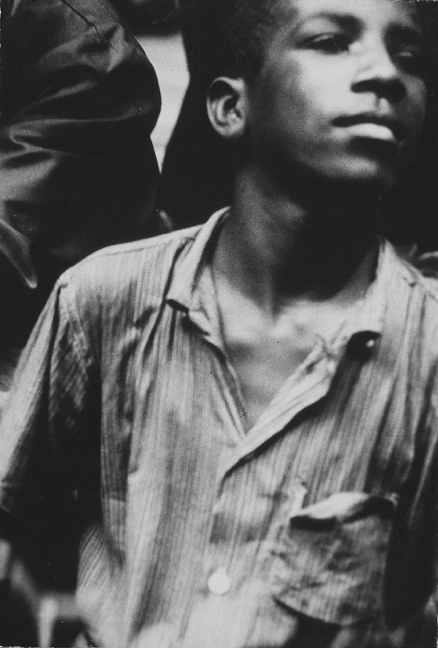

Title of photo: John Henry, Lower East Side, New York, 1960, Photo by Louis Draper, 1960.

I remember Lou and Herb clearly. They came to me in the early years of my teaching in New York. I think it was probably around 1957 or ’58. Lou was passionate and on fire. He brought in a lot of work, probably more than the other students at the time. It was as if he was a man on a mission with his work. He moved right into street photography — portraits, his neighborhood, etc. And his work really evolved quickly.

Herb was quieter, but also quite clear on what he wanted to do. He had a kind of quiet passion and I seem to recall a kind of lyrical quality to his work, pensive and beautiful. More poetry. Both of them were really friendly and open people and it was a pleasure to know them. Seeing Herb again at the Aperture event really brought me back.

Judith: What did you know about the Kamoinge Workshop back in the 60’s when it was formed?

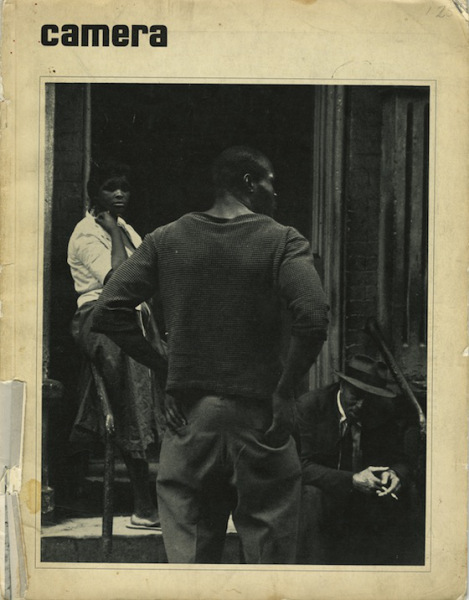

Harold: I didn’t know about it at the time. I moved to Philadelphia to teach in the early 60’s, which is when they formed the group. But I remember seeing a spread in Camera Magazine sometimes in the 60’s highlighting the work of some of the members. It was great to see that and I remember feeling happy for Lou. I think his photo was on the front cover.

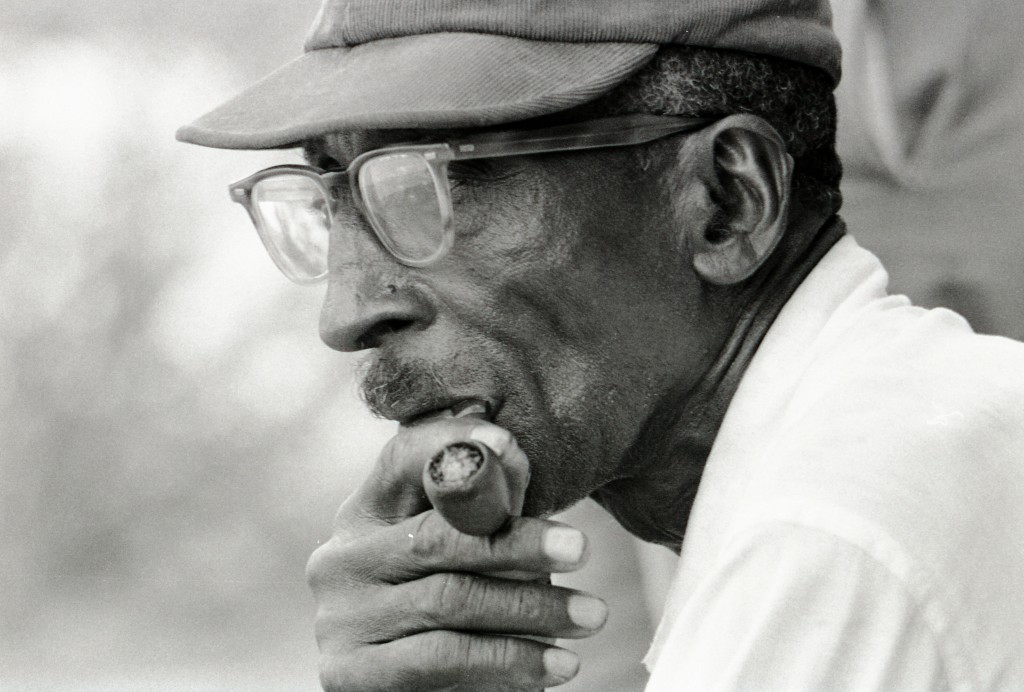

But, seeing these photos that you’re sharing with me [now from Freedom Summer] makes me appreciate where Herb took his photography. Bearing witness to history. I particularly like the portraits, but also these showing the people together making history. It’s almost hard to imagine how bad it was for so many people, but here you get to see them in the process of empowerment. That’s quite wonderful!

From my January 10th interview with Herbert Randall:

His memories of the formation of Kamoinge:

I got out of Army in 1961 and had a job at a photo lab in Manhattan in 1962. I became friendly with Albert Fennar and Jimmie Mannas who were both working there also and happened to be African American. I introduced them to Lou Draper. I had met him through Al Simon who had taken Harold’s class the year before I did. So, we were a kind of loose knit group. It was like a loose knit group. We played basketball, watched football. There were a couple of smaller groups and we called our group Kamoinge. I think the other was called Camera 35. But eventually we all got together including Lou Draper, Albert Fennar, Ray Francis, Herman Howard, Earl James, Jimmie Mannas, Calvin Mercer, Larry Stewart, Shawn Walker, Calvin Wilson and myself. Roy DeCarava, who helped shape the group and give it direction, was voted its first director. He had been lobbying ASMP to be more responsive to African American photographers and his connection to them was a good bridge for us.

Memories of Freedom Summer:

I was 28 years old and had won a John Hay Whitney Fellowship for a photographic project. I had a friend in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) office in New York who suggested that I join him for a SNCC project scheduled down south later in the summer. I thought it sounded good, but when she told me it was going to be in Mississippi, I remember saying “No way in hell I’m going to Mississippi!” But later she introduced me to Sandy Leigh, who was coordinating the project for the Hattiesburg, MS SNCC office. He came to New York to recruit volunteers and I guess he recruited me!

First we went to Oxford, Ohio, for a training session. It was there that we heard about about the disappearance of Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman. So it was a scary time.

I drove down to Hattiesburg in a car with one white guy with three white women. I had to lay down in the back seat on the floor, because the car was already targeted because it was a foreign make with Pennsylvania plates. We were followed by the police and other unmarked cars a couple of times and I was fearful for my life. One time I was being driven home to where I was staying with a local guy and his family. We were being followed and so when they got close to the house, they opened the door and I rolled out of the car while it was still moving, ran through the back door and there was John [the owner of the house] standing at the front door open and his rifle. He simply said: “Anybody bothering you Herb?” I don’t know what he knew about that car, but he was ready for them. That was one of the scarier moments in my life.

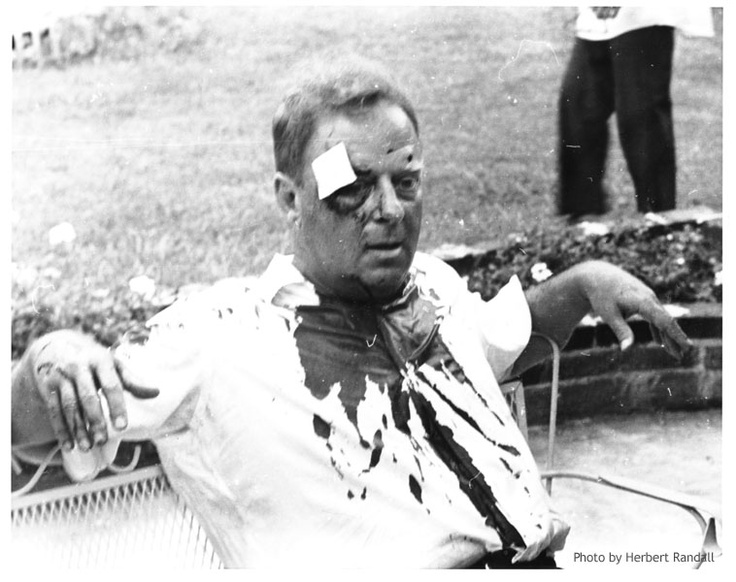

About the Rabbi Lelyveld photos

Rabbi Lelyveld had come down from Cleveland, OH to help with voter registration. He was taking his vacation time to do this. The Cleveland Plain Dealer wanted photos and let me know that. I met the rabbi and told him that the newspaper wanted the photographs. We had a long discussion and he asked me at one point: “Tell me honestly. There are a number of people coming down to Mississippi.Are they very helpful?” We had a kind of jocular relationship and I said: “Well, I tell you what would really be helpful for you and for us is that you go down and get your ass kicked. And I will come down there and photograph it and get some kind of PR from that!”

So the next day I went down to where he was doing voter registration. He and others had just been beaten and he was in shock. He was really bleeding heavily. We set him down and I knew I had to take pictures of this. So, I didn’t know what to do. Stop the bleeding? Get him to the hospital? He’s in shock and sitting there. So, he looked up at me and said “Photographer, take the picture!” And there is was sort of like a premonition.

Memories of Harold as a teacher:

Studying with Harold was the foundation for me. Everything grew from that. He encouraged me to find my own voice in photography. I put people in certain categories. In my humble opinion, I’ve met a lot of people and I thought I knew a lot of stuff. But Harold was from somewhere else. If anybody asked me if I ever meet anyone who I didn’t believe to be human — my first thought would be of Harold. I mean that in a positive sense — a very wonderful way. In fact, he may have been the only human and the rest of us weren’t. But he was from somewhere else.

A number of exhibitions highlighting Kamoinge artists from the past and present are currently up in New York. Links to them are below.