Long before there was Photoshop… photomontages

I met Georgina in Ibiza in 1987, but the Rodin sculpture accompanying her (entitled Last Sight) resides in the Rodin Museum in Paris (shot by me the same year). Each evoked the other for me, so I brought them together in the darkroom!

Last week I was asked to speak at the Endicott College School of Visual and Performing Arts, a great little gem of an art school overlooking the ocean in Beverly, MA. I was a special guest for the opening of an exhibition curated by Boston University’s Photographic Resource Center entitled “Unconventional Inventions: Innovative, unusual, and alternative approaches to photography”.

My friend Sandy Ferrier who chairs the Deptartment of Visual Communications suggested I feature my early street work, especially my Coney Island work, and my time with the Photo League — which I did. But I ended my presentation by sharing with the students, faculty and guests, my own journey with experimentation and “unconventional inventions.” I included three specific areas of experimentation — though there have been many more. I’ll save two of them for later blogs and focus this posting on my darkroom work creating photomontages.

I’ve been meaning to write a blog about this topic for sometime ever since I saw a Boston Globe article by Dushko Petrovich on a show at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art that opened last fall and closed in January 2013. The show was entitled: Faking It: Manipulated Photography before Photoshop. I’m sorry I never got a chance to see the show, but that review and others brought forward the time-worn debates — present since the inception of photography — as to what constitutes so-called “honest” photography. In this day of digital imaging and manipulation the question takes on new complexities. But following the thread of this in my own life has taken me on some interesting journeys with my own work.

I started taking photographs when I was 15 in 1946. I was a purist for well over a decade. I believed that what you saw through the view finder and clicked in that moment was the real and true photograph — not to be manipulated. In fact I was so purist that when Edward Steichen, who had been a great supporter of mine and purchased my work when I was 19, invited me to submit seven photographs for the Family of Man exhibition, I turned him down on the grounds that “themed shows” undermined photography by making the art subservient to a theme and not the unique artist and image. (Alas I was not alone in this opinion as it was a frequent critique by photographers of the time, but it is probably the decision I’ve most regretted vis a vis my photography! Here’s an interesting article by Bill Jay about the historic ramifications of that show.)

My purism was a reflection of the time. Mid-20th century street photography, as reflected by the inclinations of the Photo League, sought to show life “as it is.” At the time, we were reflecting a growing consciousness about the use of photography as social commentary — a way to present all aspects of the human condition by bringing the truth of people’s lives front and center. Yet, as Petrovich points out, even Paul Strand, a co-founder of the Photo League “wasn’t above painting out a figure that cluttered the composition in his 1915 photograph City Hall Park. (He later declared, ‘You can do anything in photography if you can get way with it.’)”

The f64 school on the west coast, consisting of folks like Alfred Steiglitz, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams, expressed their commitment to realism and objectivity through shooting with the camera’s aperture down to its smallest opening (f64) creating great depth of field and then printing from contact negatives so as to preserve the most integrity possible to the details. Yet, as Petrovich points out, Ansel Adam’s famous “Moonrise” (1941) was given its dramatic appeal by “aggressive darkroom chemistry six years after the fact.”

In future blogs I will dive more deeply into the creativity of the printing process, but suffice it to say that most photographers who print their own work (or printers under the supervision of the photographer) are employing interpretive means of all kinds to make the most beautiful photograph. This means dodging, burning, and in some cases cropping (which I was also very much against in my early career!).

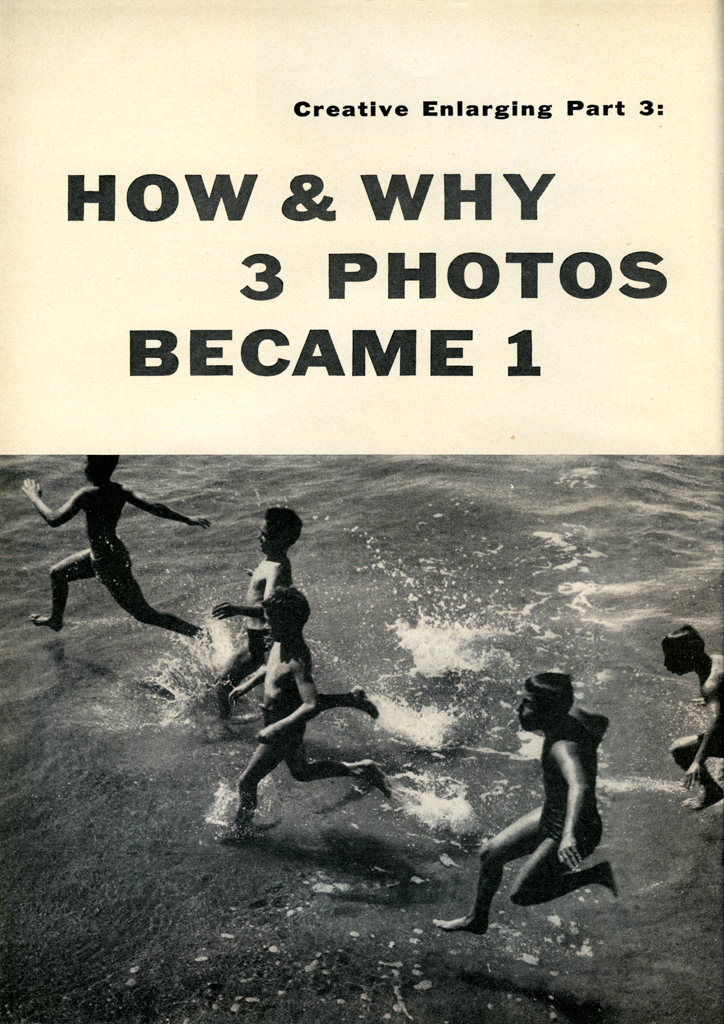

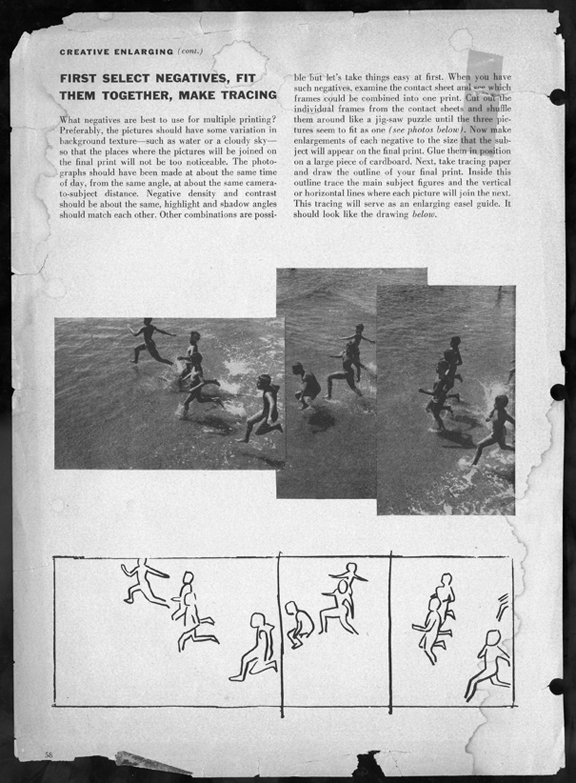

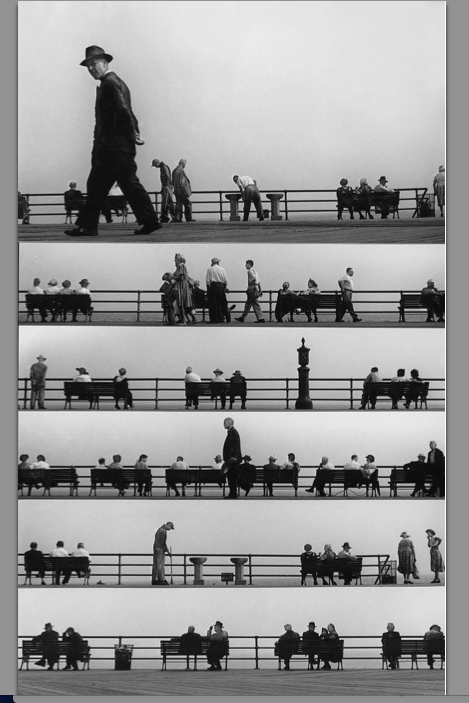

By 1957, I was into making photomontages using multiple negatives and bringing them together in the darkroom. Herbert Keppler, editor at Modern Photography and then Popular Photography was an important early supporter of my work and he often solicited me to produce articles on both composition and printing. This article scanned from an old magazine took the reader through the process I used to bring together negatives in the darkroom.

Here’s the photograph from that article:

Now they’re diving — also three negs!

On this page they ask the question:

“How far can you go with multiple printing?”

There’s a wise expression: “Hardening of the categories causes art disease” (generally attributed to my good friend W. Eugene Smith, though I actually think I said it first!) Once we think we’ve defined what art is, or what photography is, we’ve limited our artistic imagination. Now I’m not saying I like all art or all photography, but I do encourage my students to go with whatever calls them and play with it. Be true to your own form of expression, because you’re the authority of your own art.

Here are a few more photomontages birthed from my imagination!

The sheep are from Ringoes, NJ and the sky is from Coney Island!

Harold, I love the comment about “Hardening of the categories,” and heartily agree! It definitely sounds like something you would say. Allan MacGregor

In any case….I do say it a lot — regardless of who started it! Just looking to keep the hardening out of my categories (and my arteries!) Can’t wait to see you soon!

What a great article. I am so glad that your history is being shared, Harold! You have been doing magnificent work for over 65 years…don’t lose a second of this story…get it all down in print to share with the rest of us! 🙂

Luckily I have your sister, my dear wife, to help me out!

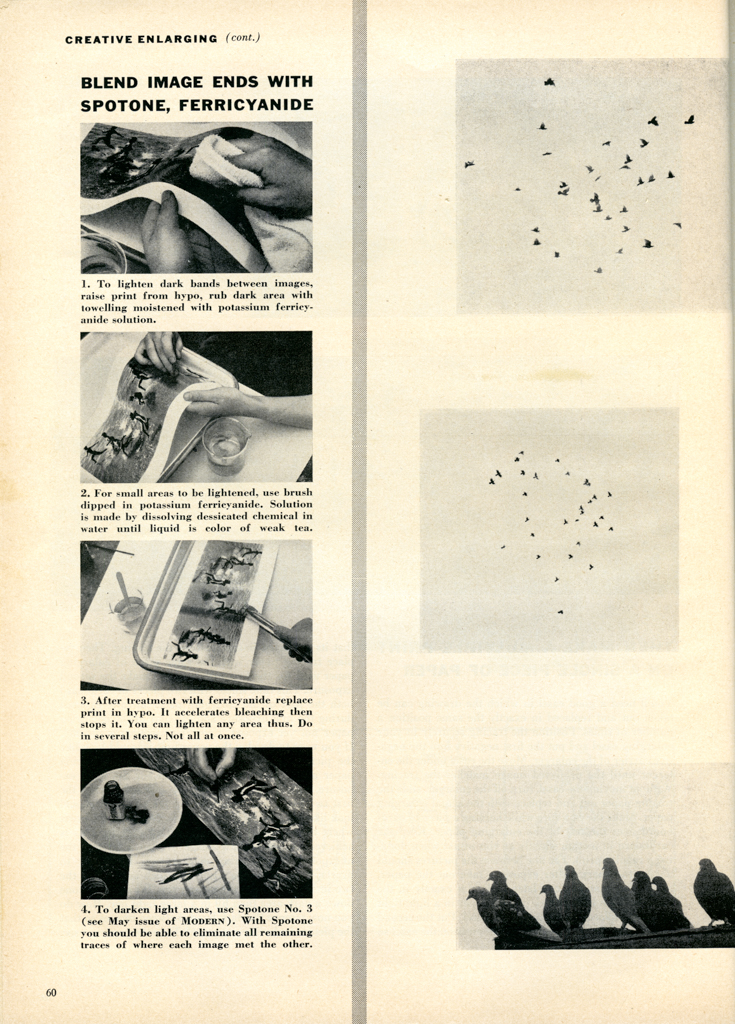

Very excited to see how the pigeons came to be since I own it!!

You are one of the truly creative beings!

Xo

JoAnn

Great seeing you at Aperture Joann. Hold onto that Pigeon photo! Might be worth a small fortune someday (wondering if I get more per neg?) Best to you

Back in the 1960’s, under the influence of Cartier-Bresson and Alvarez-Bravo, I too, believed that the camera didn’t lie. Of course another hero was W. Eugene Smith. His camera also didn’t lie. It, like those of the others, showed exactly what the photographer wanted seen: what he selected, waited for or even staged. As for Jerry Uelsmann…

Digital photography, more than ever, reveals the original image produced in the camera as the starting point for a creativity that ultimately comes from within each one of us.

Richard — from within. Yep…that’s where it all begins (and ends!) Thanks for your comments — Harold

Harold,

Keep up the enjoyable and informative blogs. Makes me want to start writing some myself, I’ll be 82 in August. We share an era.

Ronnie, Gilbert, Jodi, Atticus, and Chloe just left here after a 4day visit.

Cheers

Chuck

How nice to hear from you. I remember clearly so many moments that we shared together from the time I had just met Ronnie until the last time I came to visit you in VT. I know we both have a lot left to accomplish, but wait till we grow up!

P.S. I’ll be 82 in two weeks. So there! It would be wonderful if you and yours could come to visit us here in Massachusetts!

[…] 7. Georgina and Rodin — I often made montages from several negatives — and most of them have become favorites of mine. It comes from my own background drawing and painting prior to picking up the photograph. The sensibility of making using my imagination to create beautiful preceded it all. In this case there are two negatives. Rodin has always been a favorite of mine and I took the photograph of his sculpture in 1987 at the Rodin Museum in Paris. That same year, I was in Ibiza, and took a photograph of this lovely girl in front… Read more »

[…] I often made montages from several negatives — and most of them have become favorites of mine. It comes from my own background drawing and painting prior to picking up the photograph. The sensibility of making using my imagination to create beautiful preceded it all. In this case there are two negatives. Rodin has always been a favorite of mine and I took the photograph of his sculpture in 1987 at the Rodin Museum in Paris. That same year, I was in Ibiza, and took a photograph of this lovely girl in front of this particular Rodin sculpture. In… Read more »