W. Eugene Smith, Ed Thompson and the battle for creative control: A play in multiple acts

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances. And one man in his time plays many parts.” William Shakespeare, from “As you Like It”

Several months ago I received a few emails from friends pointing me to a highly entertaining blogpost written by Jim Hughes, author of the biography of Smith entitled W. Eugene Smith: Substance and Shadow. In it is a brief, yet important appearance of a then 28 year old Harold Feinstein in his role as Smith collaborator during the years of the now legendary Pittsburgh Project photoessay. The post, entitled “W. Eugene Smith at the 1959 Miami Photojournalism Conference: More Pages from the Cutting Room Floor“, (found in the terrific blog The Online Photographer) reads like tragicomedy, replete with colorful characters, high stakes melodrama, comic relief, and even political commentary. Yet at its core – all the histrionics notwithstanding – the key debate between creative control and commercial concerns was a serious one – and still is. Inspite of his reputation for being obsessive and unstable, Smith’s role – desired or not – as the key crusader for artistic freedom within photojournalism, did define the terrain on which this battle would unfold over time. This is why in his intro to the blogpost, Hughes describes the story he tells as” an important one, historically, that still needs to be told.”

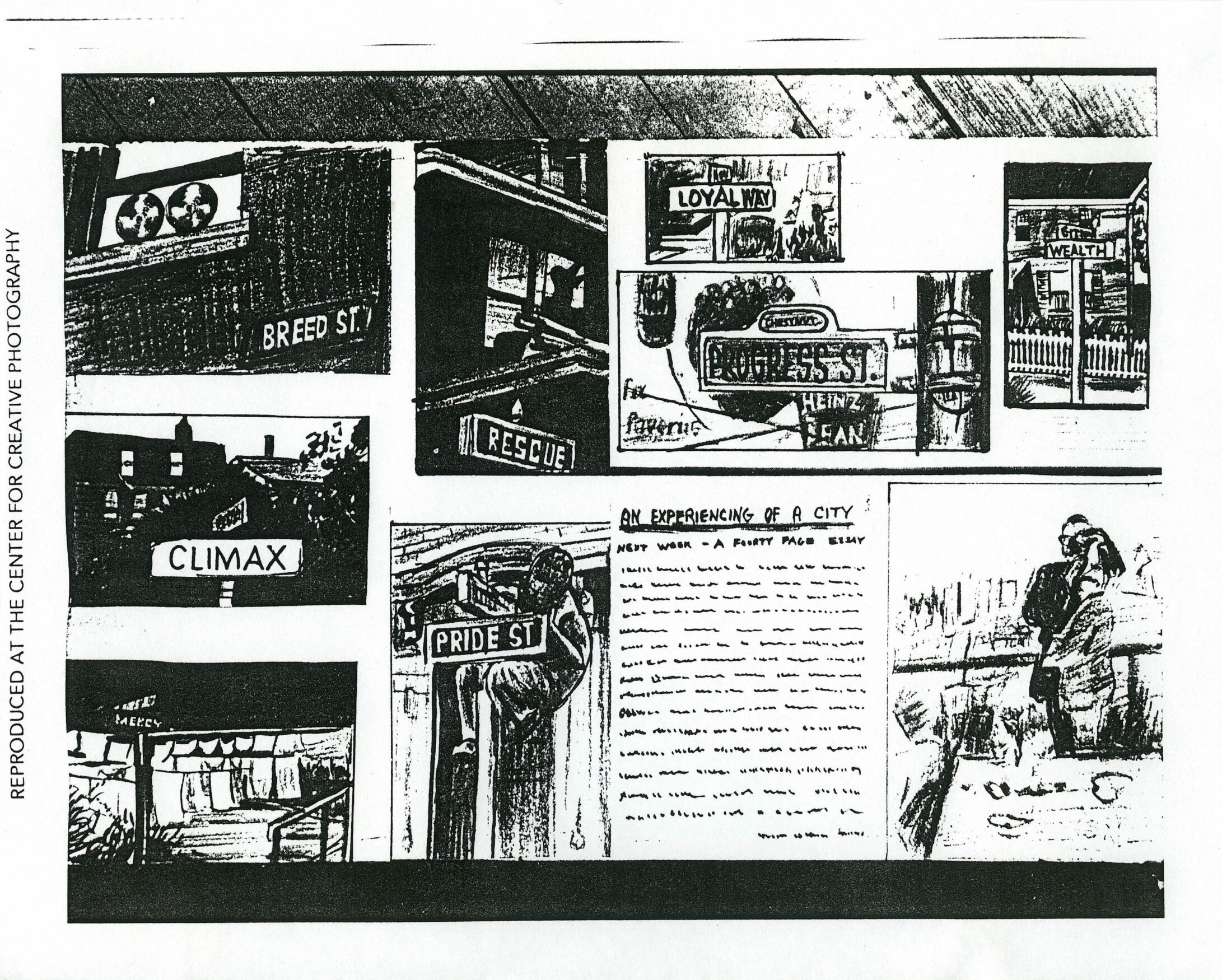

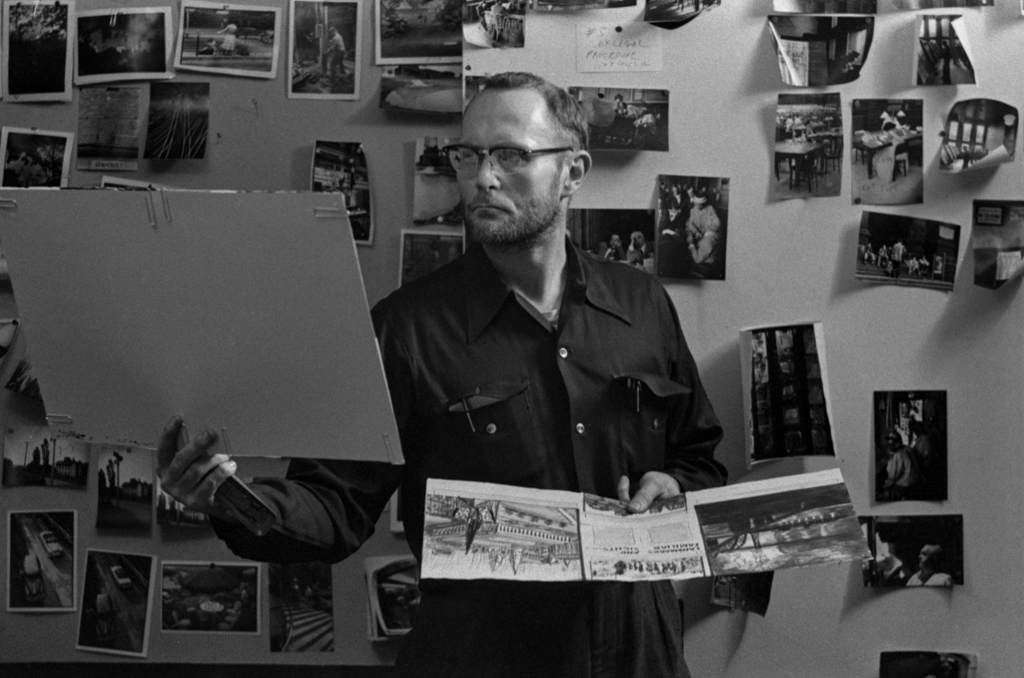

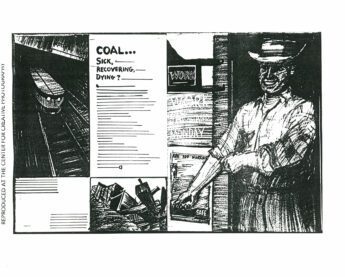

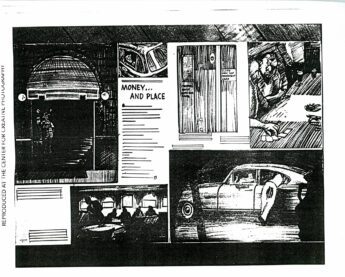

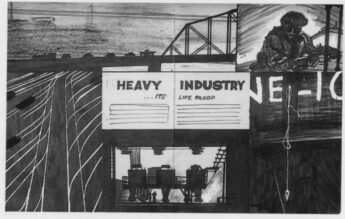

The Hughes post came to me shortly after I had come across photocopies of Harold’s original Pittsburgh Project lay-out. These drawings were renderings of Smith’s vision for what he hoped would be the published version of his mammoth photoessay on Pittsburgh. (It was, in fact, largely Smith’s commitment to the lay-out of the photoessay that put him at odds with LIFE Magazine and eventually led him to seek publication elsewhere.) Recently, in the process of editing Harold’s teaching tapes, I came across a few brief clips of Harold sharing his personal memories of Smith. These have been edited and added to our YouTube channel with links in this blogpost.

I live in a community with a wealth of local theater talent, and I couldn’t help but read Hughes’ post as theater since it has all the elements. So, inspired by Hughes’ rollicking good read (which I highly recommend you read in full), I have made an attempt to share a synopsis of his piece as it might unfold on stage. All dialogue and material in quotations is taken directly from Hughes’ post. (Apologies to serious playwrights – and to Jim Hughes – in advance for taking liberties wittingly or not!)

W. EUGENE SMITH, ED THOMPSON AND THE BATTLE FOR CREATIVE CONTROL: A PLAY IN MULTIPLE ACTS (SYNOPSIS)

The setting: The 1959 Miami Photojournalism Conference cosponsored by the University of Miami and the American Society of Magazine Photographers.

The central drama: Fresh on the heels of bitter acrimony between W. Eugene Smith and LIFE Magazine managing editor, Ed Thompson, over artistic freedom vs. the pragmatics of magazine publishing, the two enemies are mysteriously invited to be the key presenters at the Miami conference. Smith is invited to exhibit his Pittsburgh essay, which was at the crux of the above mentioned hostilities.

The relevant background: Smith wanted Thompson to publish his 32 page photoessay according to the layout he provided (illustrated by Harold Feinstein). Thompson said no and insisted that Smith cut the essay and work with the in-house deputy art director, Bernard Quint. Not satisfied, Smith took the essay to Popular Photography’s Bruce Downes who agreed to publish it to Smith’s specficiations (now increased to 38 pages), thus ending a lengthy saga meant to be a simple 3 week assignment in Pittsburgh. Smith called it “a failure that would outast it’s flaws.” (For a more in-depth understanding of the Pittsburgh Project saga see Harold’s blog post: Gene Smith, James Karales and me: Remembering the Pittsburgh Project).

The implicit but unanswered question: What was on Wilson Hicks’ mind when he brought these two adversaries together? (Perhaps he was hoping someone would write a play about it?)

The cast:

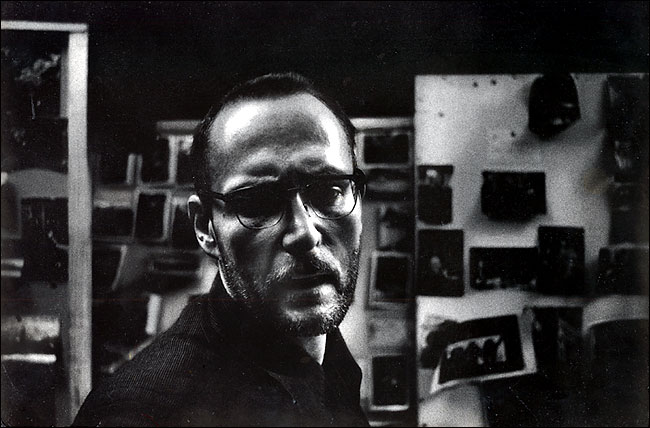

W. Eugene Smith, legendary photojournalist, perfectionist, thorn in the side of numerous magazine editors, arguably the originator and master of the photoessay.

Harold Feinstein, photographer, longtime friend of Smith’s, designer of the layout for the Pittsburgh Project.

Flip Schulke, photojournalist, then a teaching assistant, assigned to help Smith and Feinstein mount the exhibition of the Pittsburgh Project layout at the Miami conference.

Wilson Hicks, former photo editor at LIFE magazine, at the time, a lecturer in journalism at University of Miami and organizer of the Annual Photojournalism Conference.

Ed Thompson, managing editor, LIFE Magazine, W. Eugene Smith’s nemesis during the struggle to publish the Pittsburgh Project.

John Durniak, then associate editor at Popular Photography (later to become Picture Editor at the New York Times.)

Romeo Martinez, legendary editor of Swiss Camera Magazine and organizer of the Venice Biennial of International Photography.

Scene one – The All Night Drive to Miami: Gene, Harold and Smith’s wife, Carmen, load up Smith’s station wagon with Feinstein’s entire lay-out of the Pittsburgh essay and some of Smith’s choice prints from the series and a few others. They are loaded up “window to window and floorboard to roof.”

Scene two – Putting up the Pittsburgh essay: The three weary travellers arrive in Miami after driving all night with only a few hours to spare before Ed Thompson delivers the opening talk at the conference. Flip Schulke is up and waiting and they go to work mounting the exhibition. He recalls:

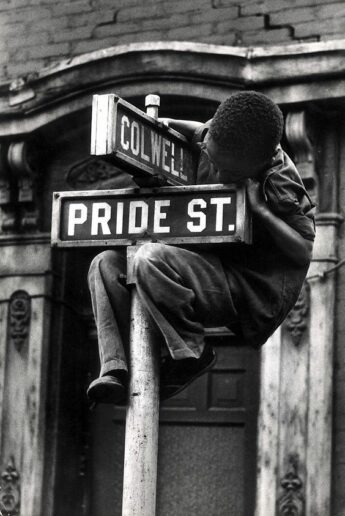

“There were just hundreds of prints, covering every inch of floor…It was like a dictionary, like an encyclopedia…Nobody had seen the entire Pittsburgh essay. He had a linear story there. He changed my life.”

Scene three – Ed Thompson speaks and the lights go out: A thunderstorm interrupts Ed Thompson’s keynote speech entitled “Who’s Looking? Who’s listening?” wherein he explains the limitations of space inside the covers of LIFE in relation to the number of stories they get every week and what collaboration should look like between photojournalists and editors. Gene Smith is in the back of the room and Thompson believes he’s gone to sleep. The storm cuts all power.

Thompson: “They gave me a flashlight with a red lens on it and I couldn’t read my notes. So I decided to take the opportunity, just to get it off my chest, to say that in Gene’s notable stories, the ‘Midwife,’ ‘Spanish Village,’ and so forth, in each case someone else had spotted the subject and gotten the factual material for backup. I didn’t think I made much of an impression.”

Narrator, Jim Hughes, speaks to the audience (in this hypothetical play): “[It should be noted here that for the two essays specifically cited by Thompson, and many others published by LIFE, my subsequent research consistently showed the opposite to be true. Gene Smith always proved to be his own best researcher. Smith surely heard Thompson’s self-serving comment; that he held his tongue is a testament to Smith’s restraint at that difficult moment, particularly in light of Thompson’s earlier reluctance to publish Pittsburgh as envisioned by Smith. But Gene’s apparent composure would be short-lived. —J.H.]”

Scene four – The storm grows: In a nearby hotel a party is winding down in the wee hours of the morning. Much alcohol has been consumed. In the room are Gene Smith, Ed Thompson, John Durniak and Romeo Martinez. Smith has still not slept.

Romeo Martinez tells us that an “epic confrontation” is brewing between the two adversaries.

Smith: “Someone asked what I thought of the Pittsburgh essay [as just published in the 1959 Popular Photograph Annual], and I said I thought it was a failure that is going to outlast its flaws. Thompson glared at me with the most diabolical look in his eye that I had ever seen.”

Thompson: (as told by Romeo Martinez): “I do my job as I intend to do it, and you think that I sacrificed you. All right, you can think that. I had to protect what I am doing, and not what you are doing.”

What happens next is told in two versions. According to Thompson, Gene breaks down and cries and Thompson carries him to his room. According to Martinez, around 6AM Thompson announces that he has to catch his plane and leaves.

Martinez: “They looked at each other, and it was a moment when I suspected the two men would come, finally, one toward the other. From Gene it was very clear. Fortunately for the sake of Gene’s pride, Thompson just turned and went out.”

Scene five – The debate gets unpacked: Martinez delivers his talk and declares:

“Creative photographers are rule breakers, while editors tend to be conformists.”

An in-depth discussion ensues with Smith joining Martinez on stage. The young Harold Feinstein making an impassioned statement described by John Durniak as “one of the finest arguments for the rights of a photographer this writer has heard.”

Harold Feinstein: It’s not a matter of communication, it’s a matter of what you have to say. It’s the man, and what the man has to say…The greatest problem seems to be to move the photojournalist into being himself, into revealing himself. You are seeing the revolution (pointing to the wall) Here it is.

An unknown editor jumps to his feet in opposition:

This business of aesthetics in photojournalism—it is a thing that we can handle [only] occasionally, mainly because people read magazines, they don’t look at them. You cannot assume—any more than a Van Gogh or a Hemingway can assume—that you have communication through being an artist. You can express yourself, but you can’t assume you have communication. Communication is a thing that people get through understanding, let’s face up to it, through mediocrity.”

Smith responds:

“I don’t think that, necessarily, mediocrity will communicate best… I think that there has to be such a superb clarity, at times, that there may be many levels, which can be interpreted, and I do believe that in such instances there has to be a very direct, straightforward level. But I also think that there should be quality in the photography, or the story, or the layout, or the writing, which can build for those who are usually insulted by picture magazines.”

Scene six – “W. Eugenius Smith”: The conference is almost over and Smith gives the final talk. He and Feinstein have again stayed up all night to take down the Pittsburgh layout and put up a small retrospective of Smith’s most notable photographs, including those from the essays Thompson had referred to so disparagingly in his opening talk. Wilson Hicks introduces Smith offering high praise for his art: “Here’s perfection!”

Smith speaks on “The dream of photography” saying:

“It has been my own great adventure. It was always something that had an automatic goal which moved on and on and on. Wherever I reached, it reached even further. I never dreamed that I could never see the horizon of it, where its limitations rested. I have limitations. I don’t know where the limitations of photography are. I have never seen them.”

Then he extols his listeners:

“There is a way to reach the average reader and not alienate the un-average reader…I believe the future is where it is possible, and must be possible, to take this profession from however far it has come and to see and to grow with it…. We have a great many problems of understanding in the world today, and they are grave…. I have both dread and excitement in this age that we are being born into. I don’t know where it will go. I am not sure I can keep up with it. But it is tremendous with danger and potential of greatness. And I think one of the things we must try to do is to find a way within that to preserve a measure of the greatness of past cultures, and the dignities that have been possible.”

The scene closes with Hick giving Smith the A.S.M.P.’s Photographer of the Year plaque for his “inspirational force” as for past accomplishments. He calls him: “W. Eugenius Smith”.

Scene seven – From the frying pan into the fire: Smith and Feinstein pack up the station wagon again to return back to New York and somewhere in North Carolina they pass a black sharecropper’s cabin on fire.

Feinstein: “We pulled off and went to help this guy who was running in and out of the house with his meager belongings. Both Gene and I began running in and out, too, carrying out what we could. But at one point, it became an inferno. I stopped, and the man whose house it was stopped. But Gene kept going in. Finally I grabbed my camera and photographed Gene carrying out some sort of picture in a frame. That photograph says a lot about Gene. It also wasn’t lost on me that I was the one standing there with a camera, and not the other way around.”

Smith: “I kept trying to find whatever legal papers the man had. Keeping an eye on the ceiling which was about to cave in, I made another trip and when I came out, all these whites were lined up on the road, just kind of enjoying the scene. I was furious.”

The curtain falls, but the play goes on…..