“Make Freedom Real”: James Baldwin on art, truth and change in America

The sea change we’re seeing in this country and the world is unlike anything we’ve ever known. I am reminded of the the lines from Christopher Fry’s play The Sleep of Prisoners:

The human heart can go the lengths of God…

Dark and cold we may be, but this

Is no winter now. The frozen misery

Of centuries breaks, cracks, begins to move;

The thunder is the thunder of the floes,

The thaw, the flood, the upstart Spring.

Thank God our time is now when wrong

Comes up to face us everywhere,

Never to leave us till we take

The longest stride of soul we ever took.

Affairs are now soul size.

The enterprise

Is exploration into God.

Where are you making for? It takes

So many thousand years to wake,

But will you wake for pity’s sake!

Writing this blog post now, in a time when “the frozen misery of centuries” seems to be breaking open; when “affairs are soul size”; when we contemplate Covid-19 and #BlackLivesMatter, and when we celebrate Gay Pride as well, it is the words and moral magnitude of James Baldwin who comes to mind. As an African American man, a gay man, a writer and social critic, a stinging and loving voice of truth during the Civil Rights movement of the 60’s, an intellectual giant with an unwavering moral compass, Baldwin, in my thinking is someone whose integrity and breadth extends across time, generations, and social issues. Always relevant, always revealing, always riveting.

“I think that the inability to love is the central problem, because that inability masks a certain terror, and that terror is the terror of being touched. And if you can’t be touched, you can’t be changed. And if you can’t be changed, you can’t be alive.”

When Harold and I first met in the late 80’s we were both reading James Baldwin. I was absorbed in Baldwin’s Letter to my Nephew, the first of two essays in his classic, The Fire Next Time. Harold was reading the essay The Creative Process (Creative America, Ridge Press, 1962) and was appreciating Baldwin’s articulation of the artist’s role within society as “the incorrigible disturber of the peace ” — a mantle not taken on in some deliberate sense, but more by the fact that artists derive their creative fuel from probing their interior and following it’s dictates, which often leads them into territory at odds with social norms. While Baldwin’s words have obvious resonance with this moment in history, they have always been relevant to the American experience in particular, and human experience in general.

“The dangers of being an American artist are not greater than those of being an artist anywhere else in the world, but they are very particular. These dangers are produced by our history… This continent now is conquered, but our habits and our fears remain…And, in the same way that to become a social human being one modifies and suppresses and, ultimately, without great courage, lies to oneself about all one’s interior, uncharted chaos, so have we, as a nation, modified or suppressed and lied about all the darker forces in our history. We know, in the case of the person, that whoever cannot tell himself [sic] the truth about his past is trapped in it, is immobilized in the prison of his undiscovered self… We are the strongest nation in the Western world, but this is not for the reasons that we think. It is because we have an opportunity that no other nation has in moving beyond the Old World concepts of race and class and caste, to create, finally, what we must have had in mind when we first began speaking of the New World. But the price of this is a long look backward whence we came and an unflinching assessment of the record. For an artist, the record of that journey is most clearly revealed in the personalities of the people the journey produced.

Societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real.”

“The terrors homosexuals go through in this society would not be so great if the society itself did not go through so many terrors which it doesn’t want to admit. The discovery of one’s sexual preference doesn’t have to be a trauma. It’s a trauma because it’s such a traumatized society.”

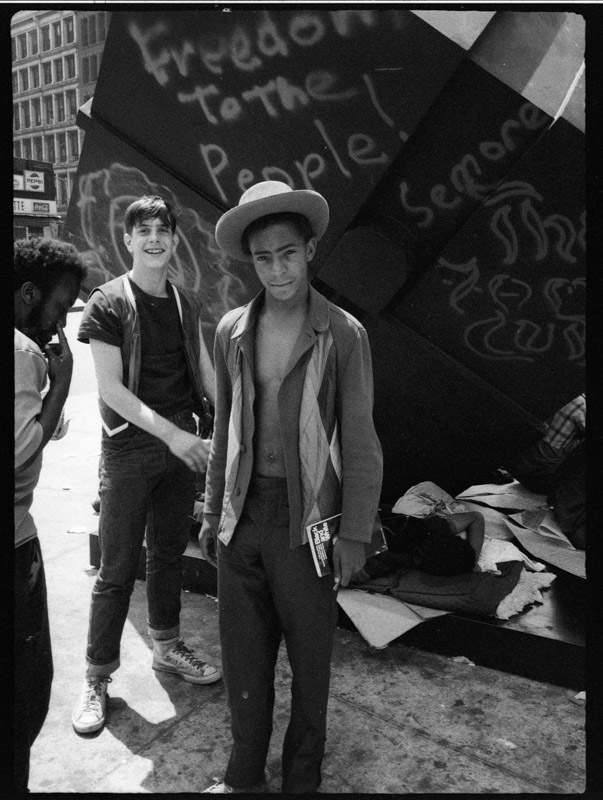

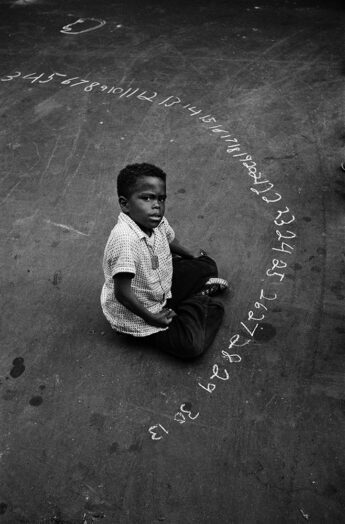

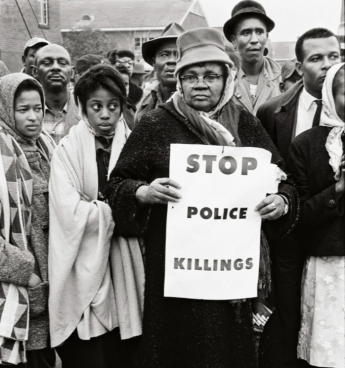

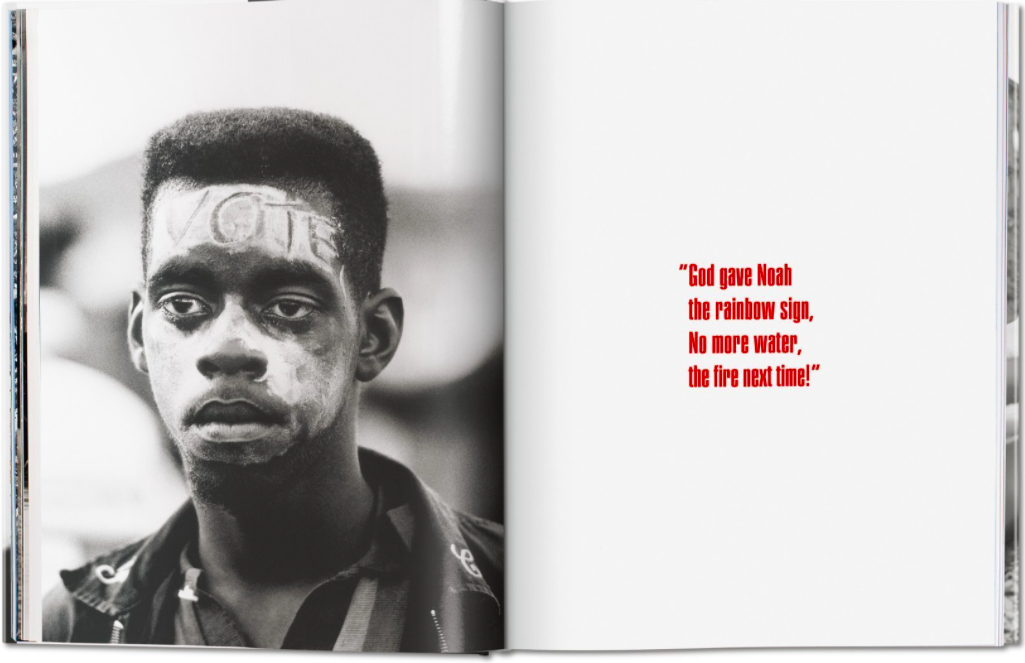

Baldwin is often referred to as “the scribe” of the Civil Rights movement. Photojournalist Steve Schapiro convinced LIFE magazine to let him travel with Baldwin through the South, where he captured pivotal actions unfolding in the movement. Baldwin’s incisive words and Schapiro’s magnificent black and white photographs were brought together in a new release of The Fire Next Time (Taschen, 2017). The partnership of these two artists amplified the message with renewed force. Viewed anew through the filter of 2020 and the sea change sparked by the death of George Floyd, these two artists’ partnership is a compelling testament in a long lineage of artistic expressions exposing the realities of the African American struggle for freedom.

“God gave Noah the rainbow sign. No more water, the fire next time!”

A new generation of inspired young women and men are now growing a new movement; seeded by those before them, who, like Baldwin, have left their mark on the consciousness of individuals and the collective. Baldwin — the consummate artist, intellectual and moral genius — “did war” with his beloved society because he longed for what he hoped it could become. Martin Luther King, Jr. reminded us: “The arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice.” It does seem like that arc is bending now, pulled by the groundswell awakened at last by the undeniable truths of our history that simply cannot be hidden anymore. Perhaps this is the moment Baldwin urged his nephew to believe in when he said:

“The very time I thought I was lost, my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.”

May it be so.

Relevant Links

- The Creative Process, by James Baldwin

- A Letter to My Nephew, reprinted in The Progressive,

- How James Baldwin's The Fire Next Time still ilghts the way to equality, The Guardian, April 4, 2017an,

- The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin and Steve Schapiro (Taschen)

- Cornel West on Why James Baldwin matters more than ever

- The photography of Steve Schapiro

- Go the way your Blood Beats: James Baldwin on same-sex love

PREVIOUS