Making contacts! Old, new and in-between

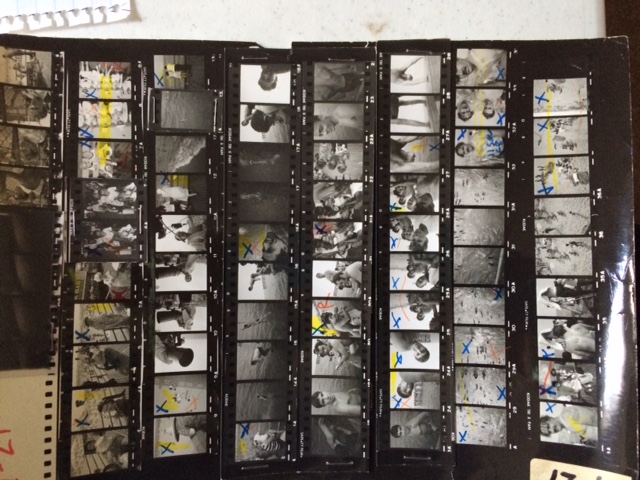

I can’t speak with a photographer’s authority about the value of a contact sheet for photographers shooting with film. But I do know from living with Harold that the film contact sheet was his primary tool for editing. And he was editing until the final days of his life! He relished finding images he had previously overlooked and having other people he trusted take part in the editing process as well. The process was made infinitely easier through digitization.

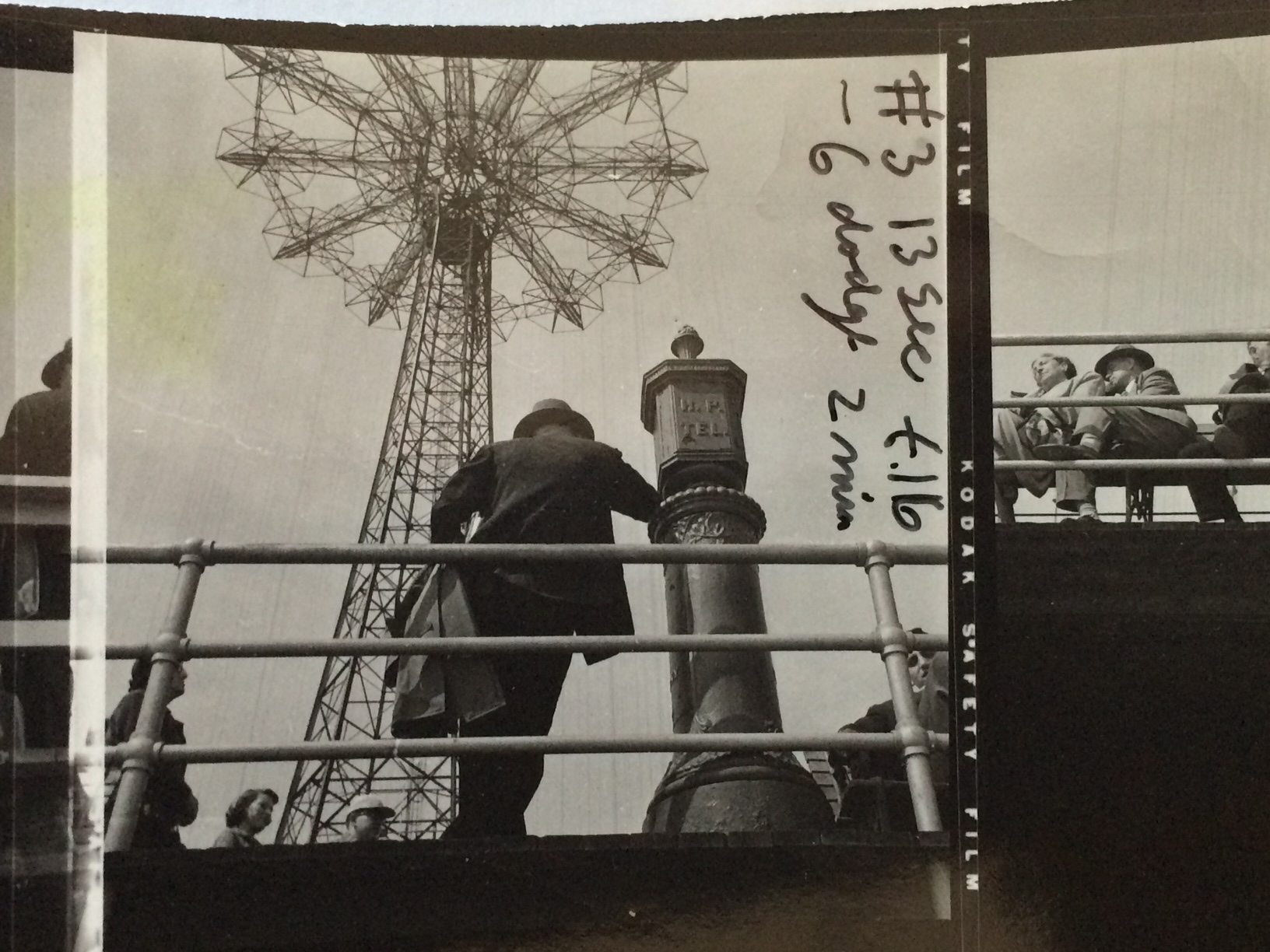

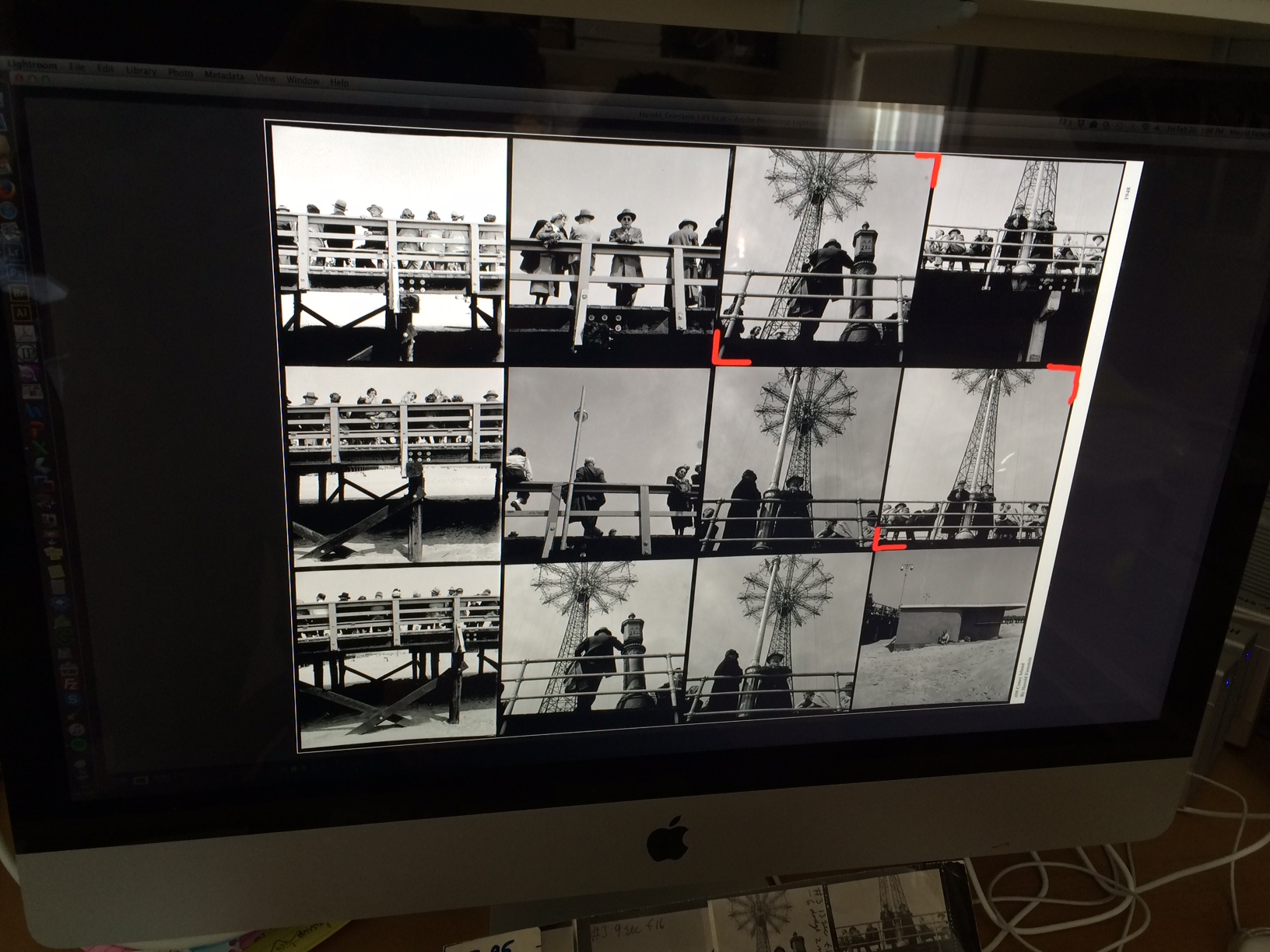

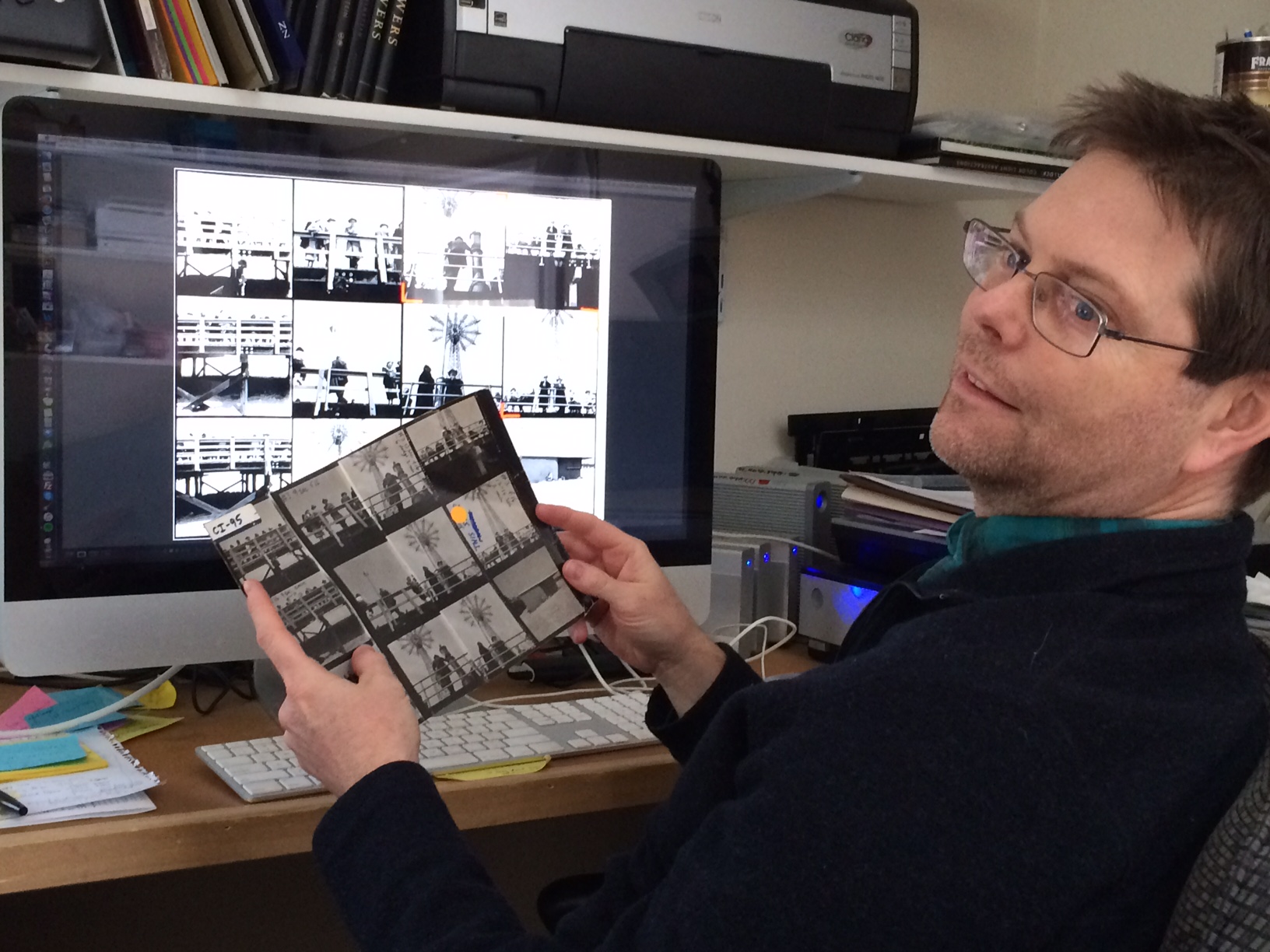

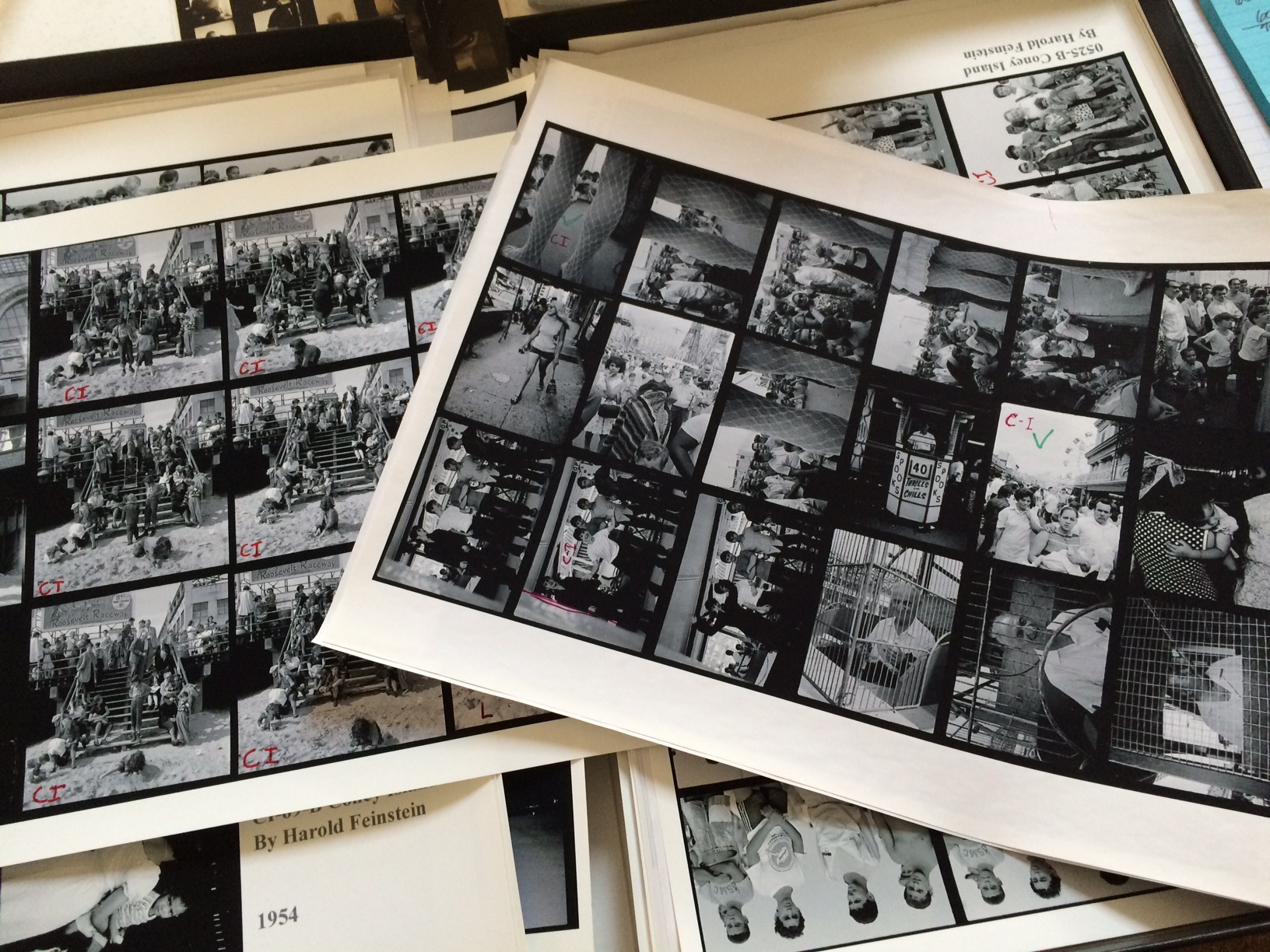

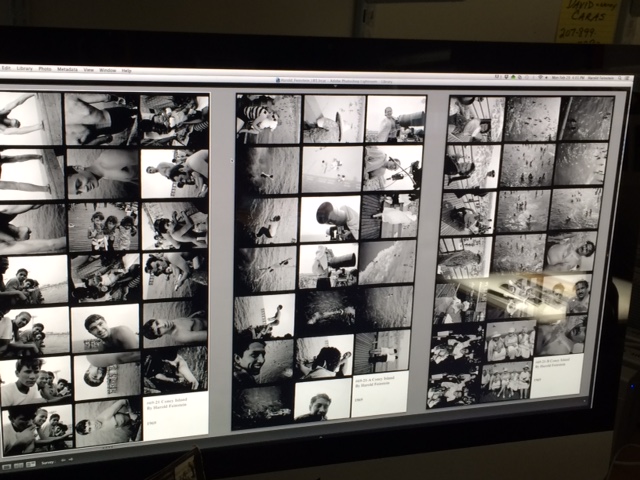

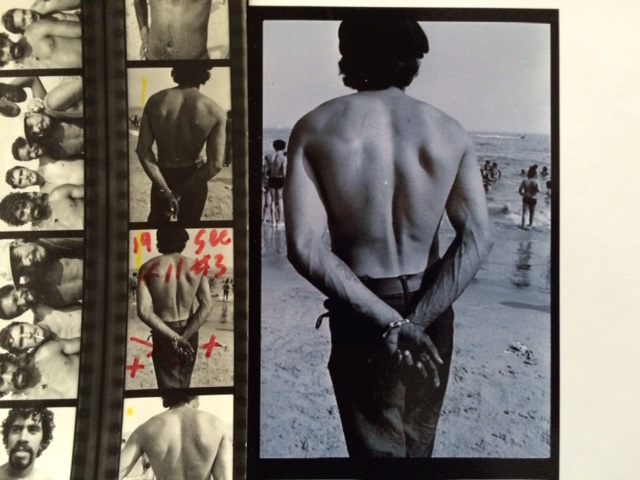

For example, looking with a loupe at an 8×10 contact sheet with either 12 (2 ¼ x 2 ¼), 18 (Widelux), 36 (35mm) or 72 (½ frame) images on it — particularly the older, fading sheets from the 50’s and 60’s — was not only tedious, but imprecise. So, digital versions of the original silver gelatin contact sheets were made by Harold’s studio manager, Cherie Burton, from 2005-2012. She scanned in each film strip and re-formed the contact sheets to match the originals. They were then available to view digitally or printed on 13×19 paper, from which they could continue to be edited. When John Benford, the current studio manager, joined the team in 2013, everything was put into Lightroom for easy retrieval. While the digital versions offer the largest view, Harold’s preference was to sit at the dining room table and handle the 13×19 inkjet contacts, and mark them for editing and scanning rather than view them on the computer.

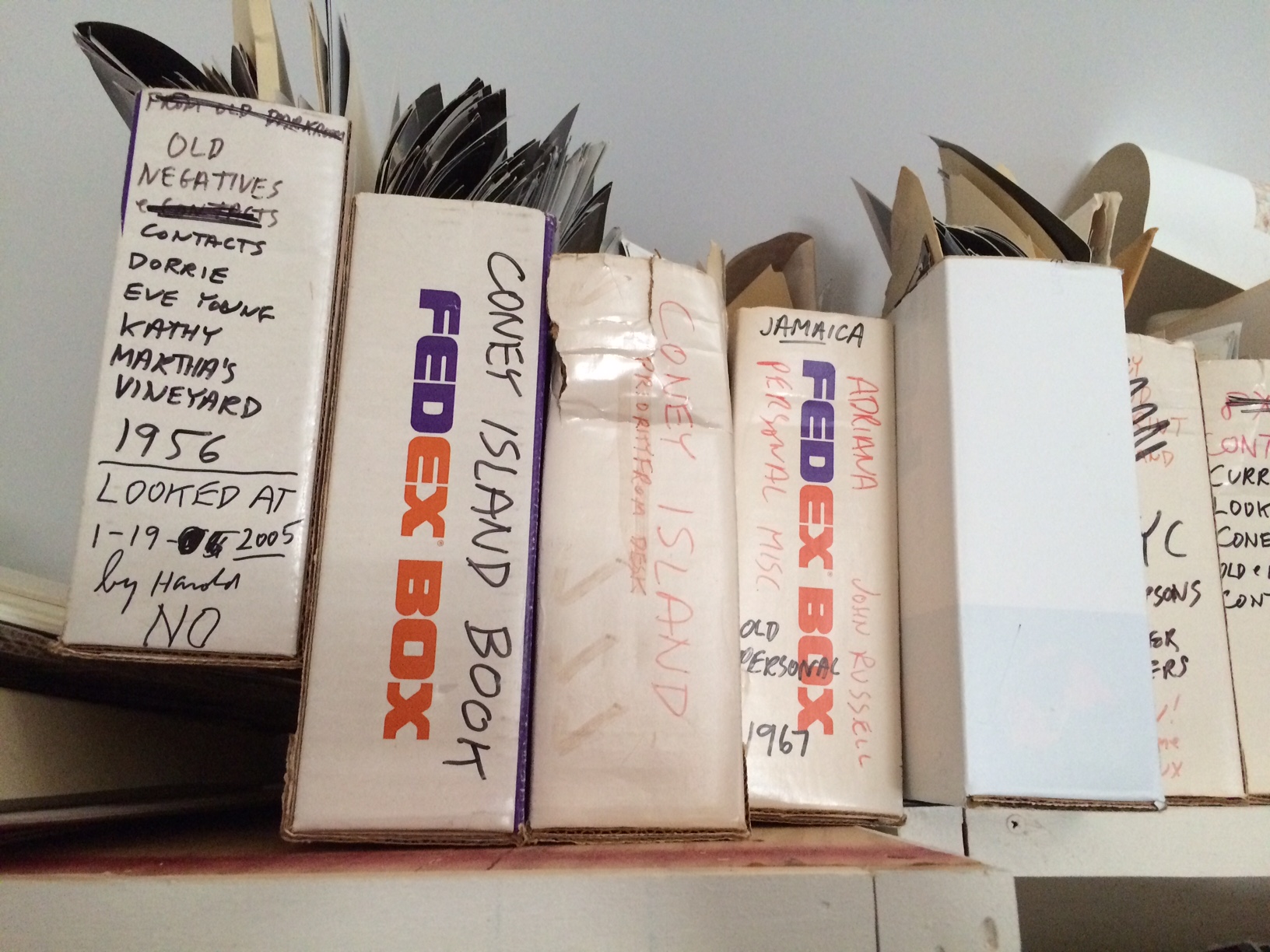

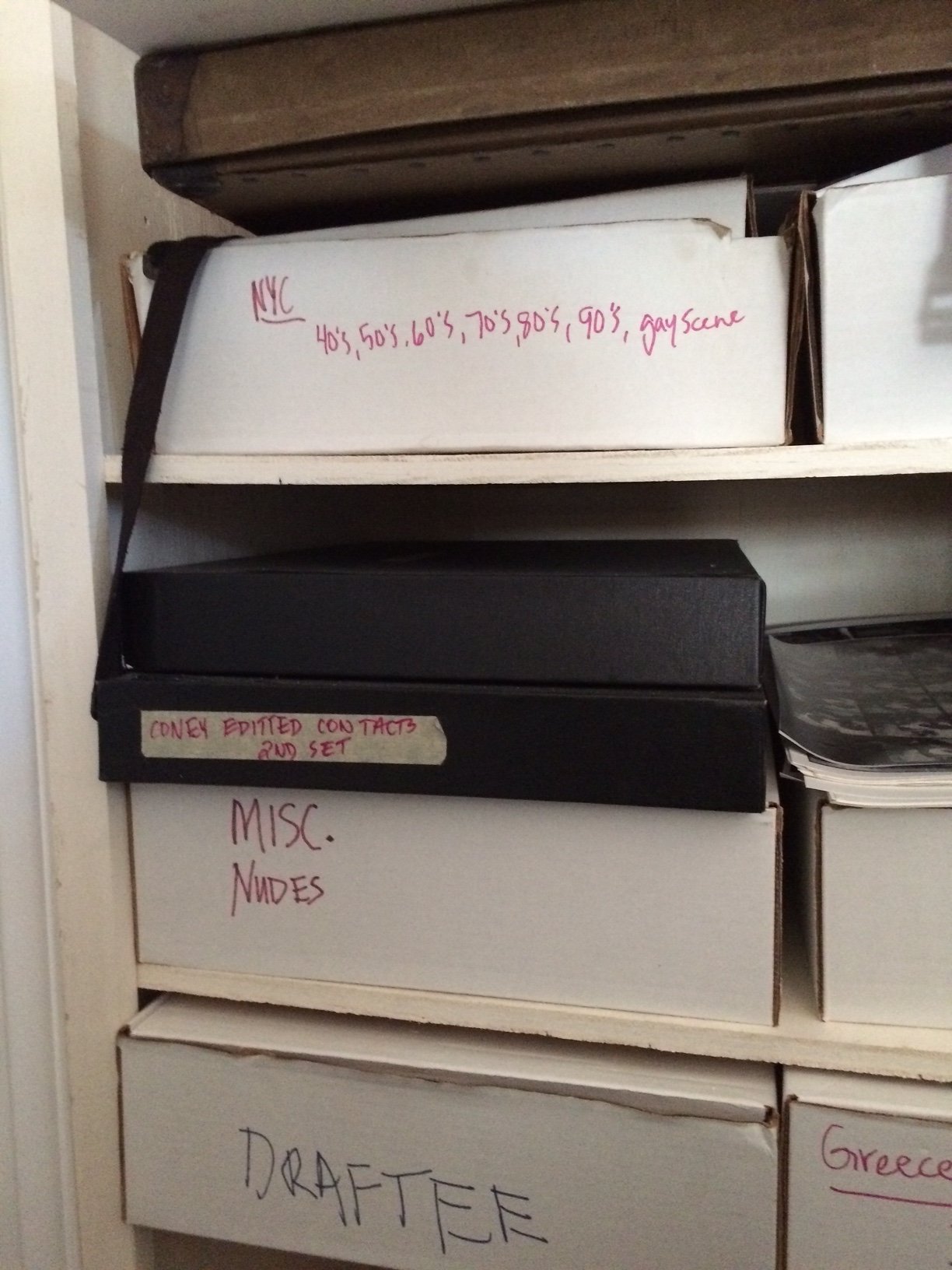

As vintage artifacts, the silver gelatin contact sheets, complete with markings and printing instructions constitute a piece of history and are still in need of some serious preservation attention since they continue to live in the old recycled Fed-Ex boxes Harold used for storing and organizing! On the other end of the spectrum, the digitized view has allowed us to see a ½ frame film negative, within a contact sheet at up to 3 x 4″ on the 27″ computer screen as opposed to the ¾”x 1″ image on the old 8×10 contact. And, in-between, the 13×19 printed contact sheets allow for easy editing for those of us who still like to handle paper and spread it out over large surfaces.

About 1350 negative strips have been scanned and made into 2350 contact sheets that match the originals by Harold’s file system (but often printed as 2-3 pages instead of one), filed in Lightroom and printed and stored in large boxes. 1300 high res scans of single frames and 1000 color slides. And on it goes! It’s hard to imagine the labors required for cataloguing before the digital age!

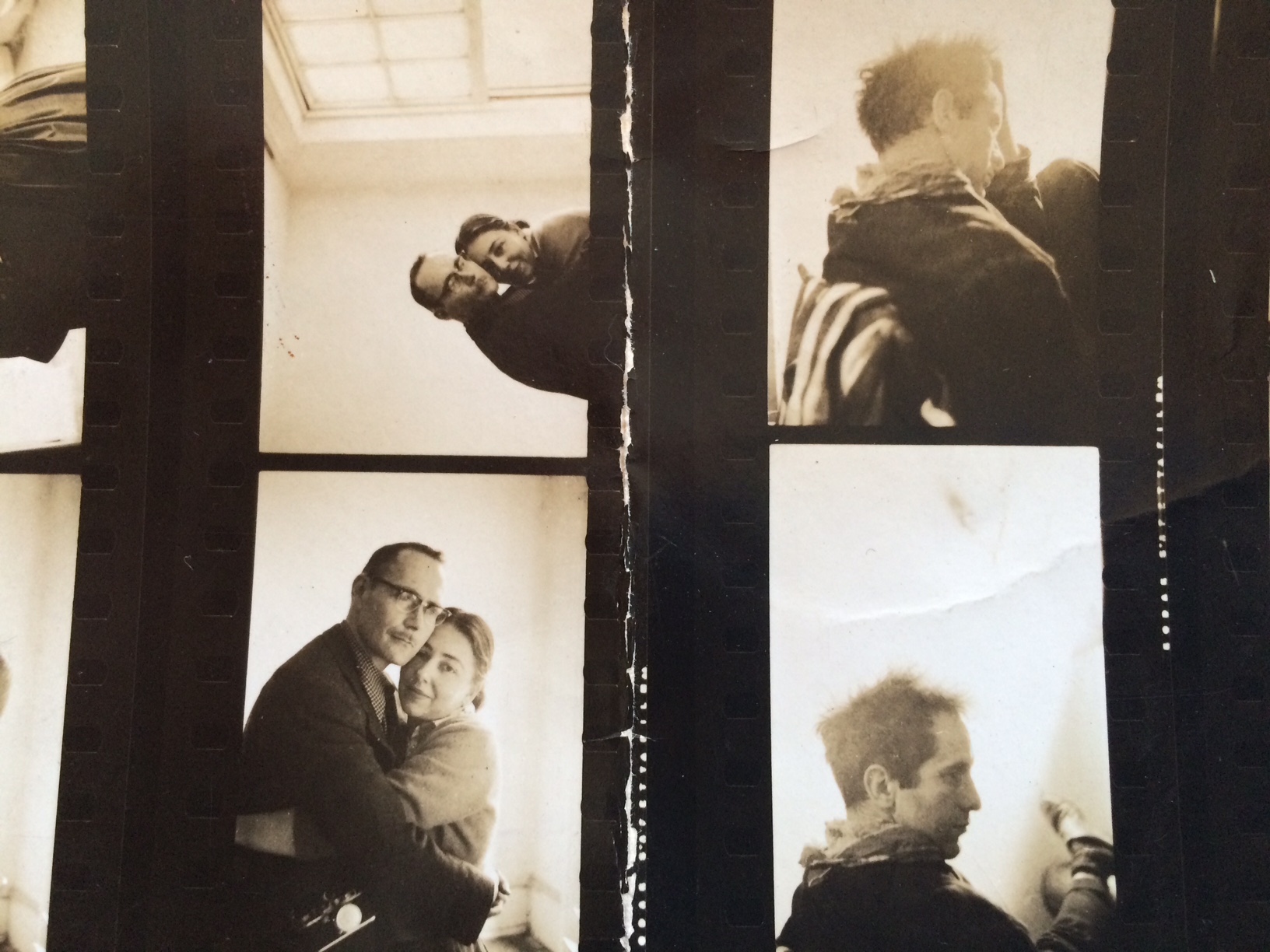

Then there are those negatives still waiting to be scanned, made into new contacts and hi-res images and catalogued — like these from the Jazz Loft years (1954-57) with W.Eugene Smith, Carol Thomas, and Robert Frank! More to do!

Curious. As you scan and digitize negatives, what allowances are you making for final prints that Harold made and in that process dodged, burned and cropped those images. In that process, it was his eye that created the final print. Have you been able to scan and digitize final prints at all?

I discovered that while having my negatives scanned and digitized. When the were returned I realize that I would have to revisit the darkroom or some contemporary image enhancement program in order to replicate the print I made some 50 years ago.

Sorry, I meant to add that along with the possibility of contemporary image enhancement, if I had final prints, I could scan those as well. However, in many cases those prints had been sold.

[…] or on paper makes the job of reviewing lots of images much easier and quicker. (See the post: Making contacts: New, old and in-between for more on this). The same is true for […]