Prints and printmaking, part 2: The allure of the darkroom

It seems appropriate to publish this second post in the series on Prints and Printmaking shortly after the Kodakery podcast, The Life and Work of Harold Feinstein with Andy Dunn and Carrie Scott published two weeks ago. After all, when Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012, the notion that a new film camera might enter the marketplace seven years later, was less than a distant dream. The Reflex, a Kickstarter funded camera billing itself as “the first new 35mm manual SLR camera design in 25 years”, is evidence of the interest young photographers are showing in analog. While it’s apparently having production difficulties and hasn’t yet hit the market, the fact that it was fully funded by the growing ranks of analog revivalists is a good sign. Another marker: Kodak Alaris‘ – the UK-based firm that rose from US Kodak’s ashes to continue producing film and paper – has decided to re-issue Kodak’s legendary Ektachrome color film, soon to be followed, if rumors are correct, by the even more classic Kodachrome.

Like many photographer’s of his era, Harold started with a darkroom in the family bathroom in the two story walk-up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. And from place to place, decade after decade, the “meditation chamber” as he called it would be the first place set up in a new home. During our 27 year marriage and five moves, the dark rooms found their way into basements, attics and guest rooms.

When I first met him, he was living in a tiny (we’re talking really small) walk-up in Greenwich Village. The darkroom was the larger of the two rooms (meant to be the bedroom), while sleeping was handled with a fold out coach just barely able to fit in next to the desk. It’s hard for me to imagine that he would cram 10-12 people into that 10x 10 room for his classes! Uncharacteristically, this little space had a bathroom with a full tub, making print washing a bit easier than in would’ve been with only a shower, and I’m guessing this is one of the reasons he rented the apartment.

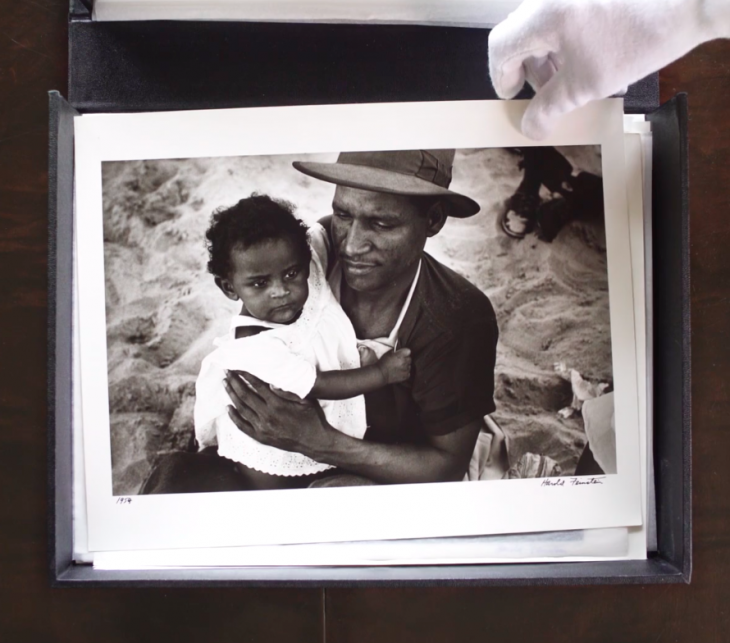

He was known as a master printer, and up until the last 10 years of his life he printed all his own work (with the exception of one friend and former student, David Caras, who had been taught by Harold and clearly had the gift.)

While he often struggled with getting into the darkroom, it was hard to get him out once he was there! “Once I got everything set up and finally got my ass in there, I would put on classical music, or jazz, explore my negatives and go into a twilight zone of timelessness. It might be 12 hours before I would re-emerge.”

“To print it is to fulfill or finish, complete the process. It was wonderful because I would see the results of what I photographed and watch the miracle of them suddenly coming up in the developer. It’s all mine…and it’s mine to do with as I please.”

“The master printer”, a clip from the documentary Last Stop Coney Island: The life and photography of Harold Feinstein. (photo above: Man smoking in diner, New York, 1974.)

“…as you’re taking the picture, there’s a certain understanding of what you can do with it when you get into the darkroom. It goes hand in hand.” Howard Greenberg

Making the link between taking the picture and what you can do with it later echoes Harold’s statement of “it’s all mine…and it’s mine to do with as I please.” The impulse of the click to capture the moment, followed by the intricacies of making the print– while different in tempo (at least for Harold who shot quickly and, by necessity, printed slowly) — were both part of one creative process. So, considering how you might be printing the photograph later was often in the back of his mind while out shooting.

For example, from an earlier blog post entitled Available Light: Coney Island at night, Harold responded to a comment from a former student who remembered Harold’s discussion of “pushing Tri-X” when photographing at night and developing it with Diafine…”graininess be damned!”

“Well yes… pushing TRI-X (from 200 to 1600) by developing with Diafine is another good way to photograph at night! But since most folks are going digital these days I don’t know how these old tricks will ever be carried on! (sigh!) The key to graininess is to print it sharply. So instead of being something you’re trying to hide it begins to define the quality of the photograph.”

According to some indications, some of those “old tricks” of shooting, developing and printing may be coming back into vogue. Some young photographers (and certainly numbers of older ones) are returning to the darkroom and reviving a real appreciation for the particular beauty of a silver gelatin print and the particular mind set required to produce one. This mini-movement includes a group of local photographers in the small city of Newburyport, MA, close to where I currently live who had their inaugural meeting a few months ago to share their common pursuit of analog photography. Luckily, there is even a darkroom in town rented out between six photographers, one of whom, Max Schenk, was in it printing for Harold at the moment of his death. (And some of the last prints Harold ever hand printed himself, in 2011, came from that darkroom managed by one of our great local photographers and teachers, Bill Franson.)

In the January 2018 article in The Guardian, “Back to the darkroom: young fans reject digital to revive classic film carema”, journalist Robin Stummer says,

“Large numbers of still photographers, professional and amateur alike, are turning their back on digital technology in favour of images with ‘soul’.”

“I enjoy working with film, looking at my negatives and taking the time to make prints”, says Mexico City photographer, Oliva Crumm, cited in the article: “The analog revival: Why photographers are returning to film”.”The labor of it is an important part of my process. When I shoot digital, sometimes it feels like my work doesn’t exist anywhere.”

Crumm’s reference to time and labor is one of the key difference between the two technologies. As Boston based photographer, Abdul Dremali, said in the same article (above), “I choose film 99 percent of the time because of the lack of instant gratification.” In a world where instant gratification has become the norm, the choice to move more slowly and deliberately may allow photographers to become more fully present to the subject they’re photographing.

Another photographer, Mico Mazzo, added: “It’s not like a memory card…You can’t shoot 2,000 photos and hope that a couple of them turn out. Because you have to think about every shot beforehand, it activates your creativity.” And, as already mentioned, it forces the photographer to think about the whole process. How will I print this particular shot? The two processes of shooting and printing become inextricably intertwined as one process.

Finally, at this panel in London, hosted by Sotheby’s during this year’s Photo London, the panelists were speaking about the “trend” in the world of collecting toward the old silver gelatin print, and how it’s appeal simply can’t be replicated in digital. In referring to the prints in her exhibition Found: A Harold Feinstein Exhibition , Carrie Scott said: “There’s something about them that’s so seductive. Just the object. You can almost read the silver on the page. There’s something about the paper, and the hands — he was in the darkroom printing this — that has an aura.”

That aura is enhanced by the fact that each print coming from a photographer’s darkroom is going to have slight variations. Consider that each individual print, run through the trays one at a time — after having already done numerous tests strips to get it just right — had to be dodged and burned by hand separately. So producing an edition of 20 prints could take the better part of a day or more, and no two will be 100% alike. (And of course in the 50’s and 60’s there was no such thing as an edition. So the photographer might print 10 shortly after printing the image and another 10 a decade later — known respectively and vintage and printed later. In that case as well, there are bound to be variations in the prints). Each print is one-of-a-kind precious artifact.

Even though Harold himself was a champion of diversity in all things, and encouraged people to experiment or choose any method for self-expression that suited them, I think he would still be secretly pleased to know that the hashtag #FilmIsNotDead has had over 10 million mentions. The beauty of analog speaks for itself!

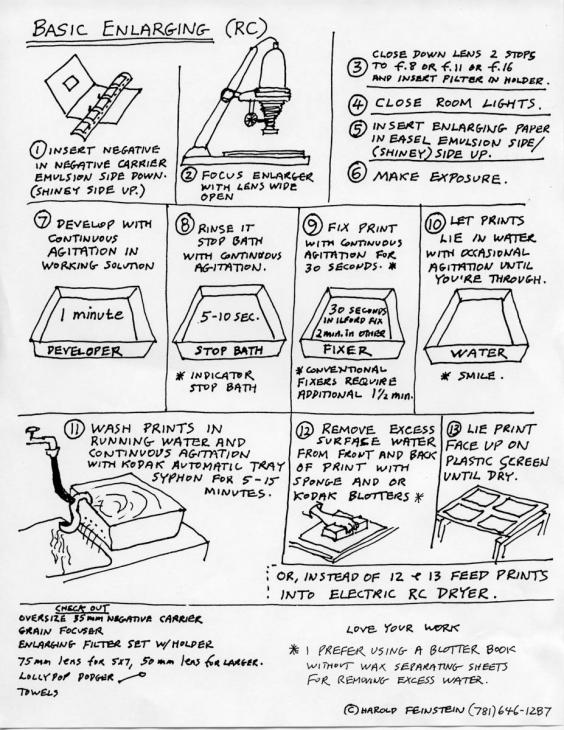

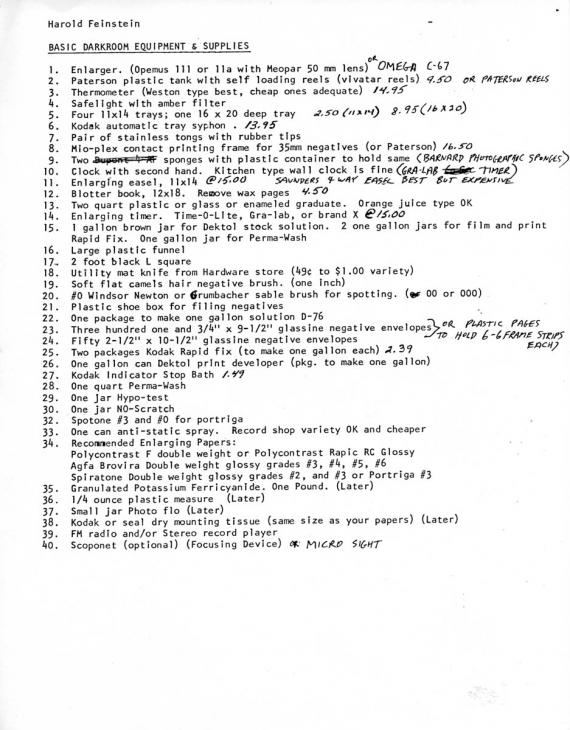

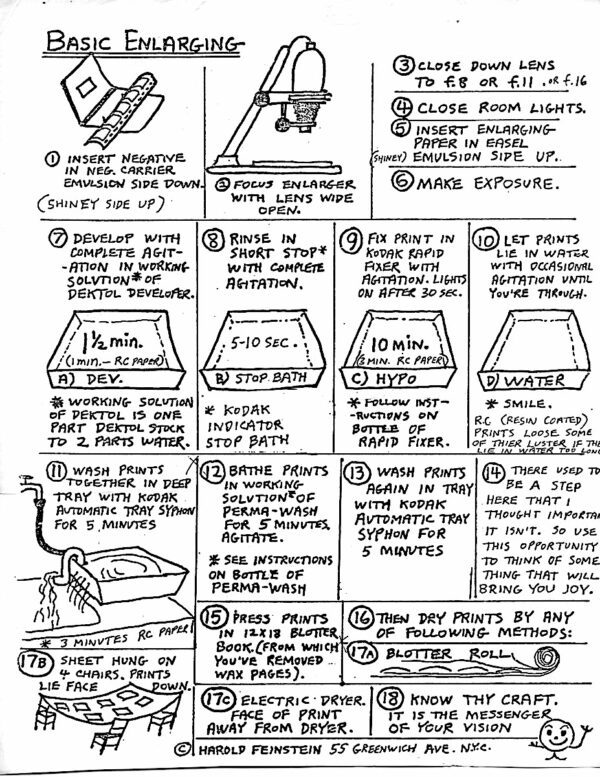

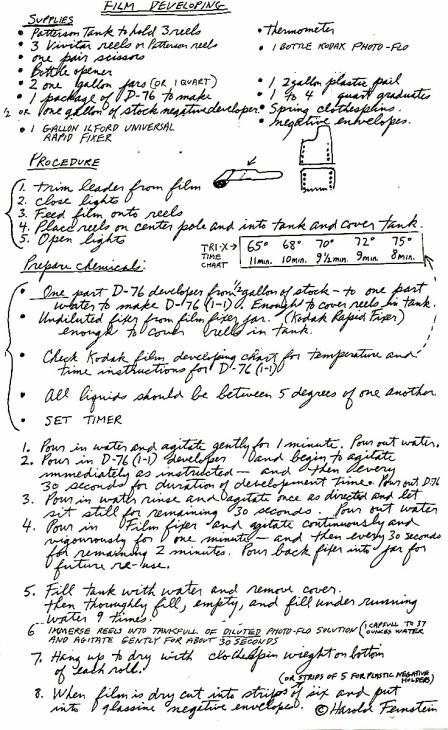

Below are a few more of Harold’s hand-outs to his students. Antiques now, but useful to those just coming back the old ways! I particularly like his little reminders (below at bottom) “Love your work”. Or this one from the hand-out at the top of this post.