Thoughts of war on Veteran’s Day

If some things don’t make you crazy, then you aren’t very sane to begin with”

Today is Veteran’s Day and I salute all those men and women who have risked their lives in the various military pursuits throughout our country’s history. I am one of them. I was drafted into the Army during the Korean War and came home with Bronze star. I had a minor non-combat-related health issue that took me off the front lines and back to Pusan to work as an artist at headquarters. I was one of the lucky ones.

I watched CBS Sixty Minutes a few nights ago about the new Secretary for Veteran’s Affairs, Robert McDonald. He was brought in to clean up the Veteran’s Administration system, especially after the scandal in the VA hospital in Phoenix, which revealed that the inordinate delay times for veterans to receive appointments (sometimes up to 482 days) was being covered up. McDonald seems to be shaking things up in a good way. After a massive firing, he’s put out a call for 28,000 nurses and doctors to help fix the broken system. Among them will be at least 2500 mental health workers to address the growing ranks of veterans suffering from PTSD.

In WWI, it was called “shell shock”, in WWII “combat stress reaction”. The Vietnam War saw “stress response syndrome”. Ultimately the terminology became post-traumatic stress disorder. But “disorder” seems a poor choice of words, implying that “normal” might mean immunity to the horrific experiences of killing, maiming and de-humanizing.

In a 2005 article entitled A Short History of PTSD, appearing in the VVA Veteran (The Official Voice of Vietnam Veterans of America, Inc.) the author, Steven Bentley, goes through a litany of examples of PTSD and wars throughout the history. As a Vietnam vet he concludes that the tremendous incident of diagnosed PTSD in those who fought in Vietnam was ultimately a sign of the sanity of those who fought. He notes that the psychiatrist Victor Frankl who wrote the inspiring book Man’s Search for Meaning and survived internment in four Nazi concentration camps during WWII shared this reflection:

“An abnormal response to an abnormal situation is normal behavior.”

The author goes on to conclude:

In other words, if some things don’t make you crazy, then you aren’t very sane to begin with. Unfortunately, it’s an idea whose time has not yet come.

My wife, Judith, who spent many decades devoting her life to assisting people from all sides of conflict to heal the wounds of war shared with me another term that is entering into the vocabulary of veteran’s lives and experiences — “moral injury.” In an excellent three-part series written by David Wood for the Huffington Post, he writes:

“Moral injury is a relatively new concept that seems to describe what many feel: a sense that their fundamental understanding of right and wrong has been violated, and the grief, numbness or guilt that often ensues… Military services, not surprisingly, are reluctant to discuss moral injury, as it goes to the heart of military operations and the nature of war.”

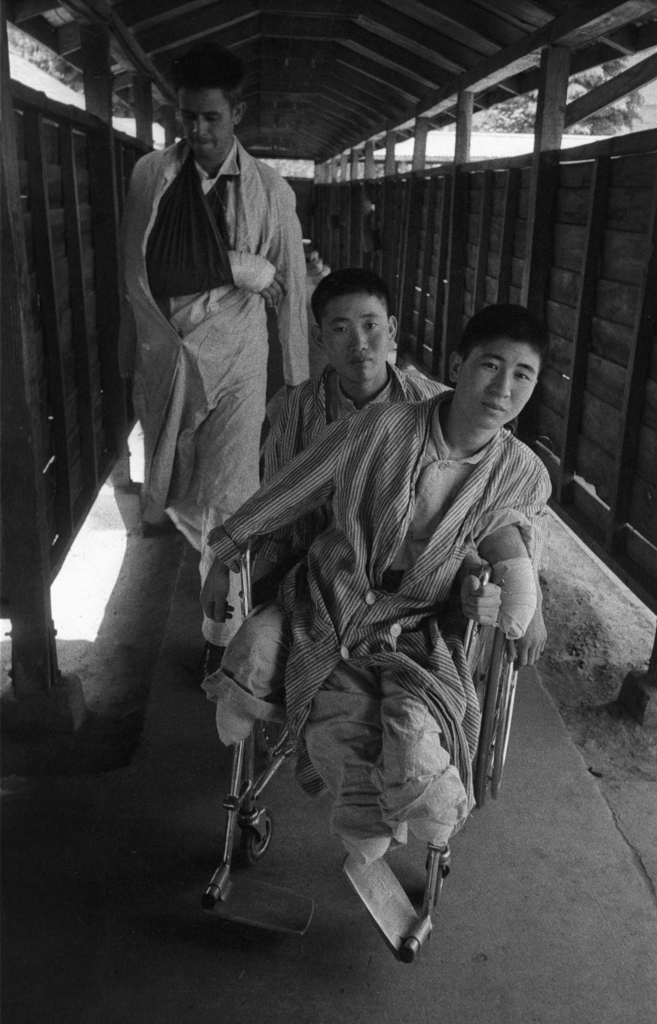

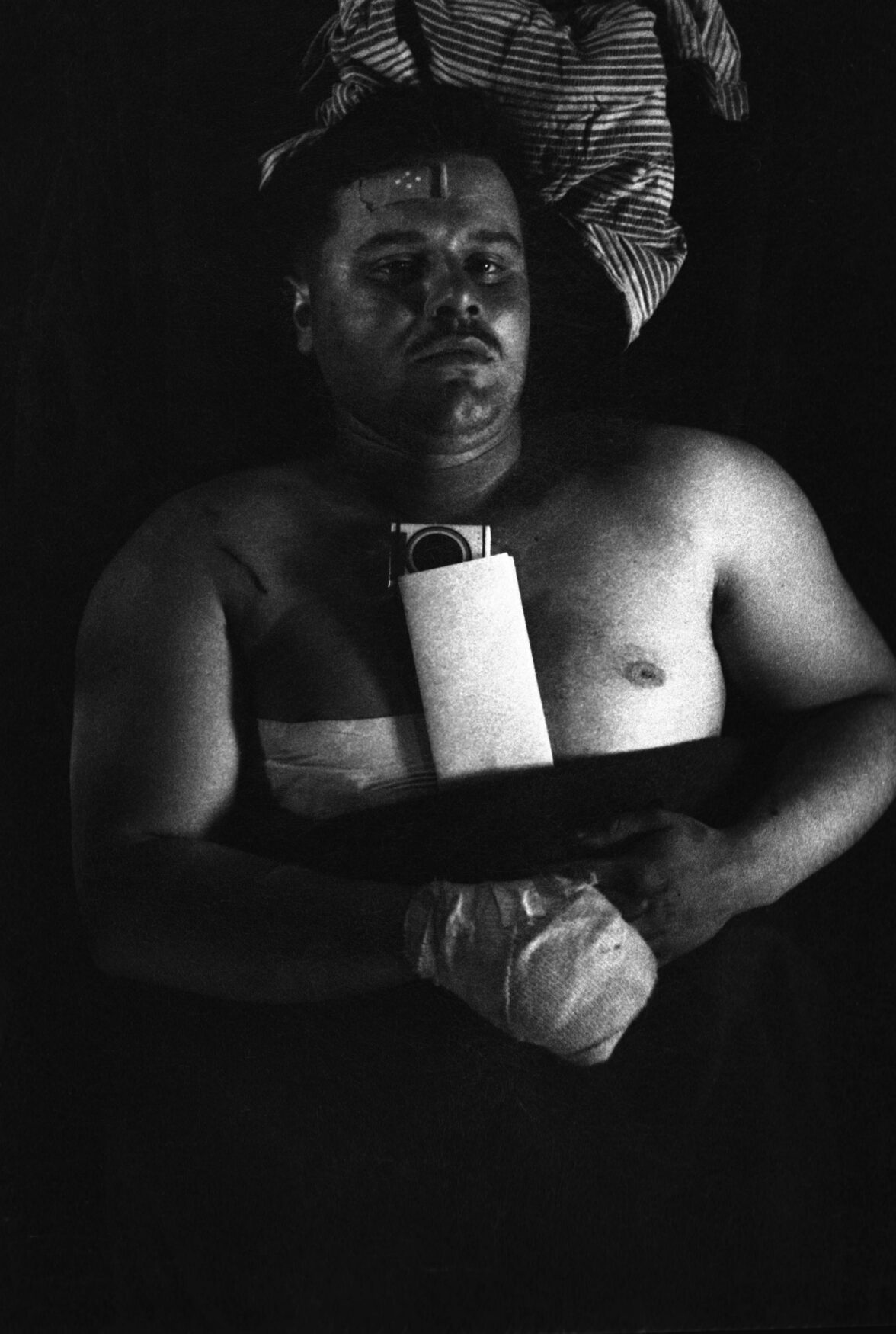

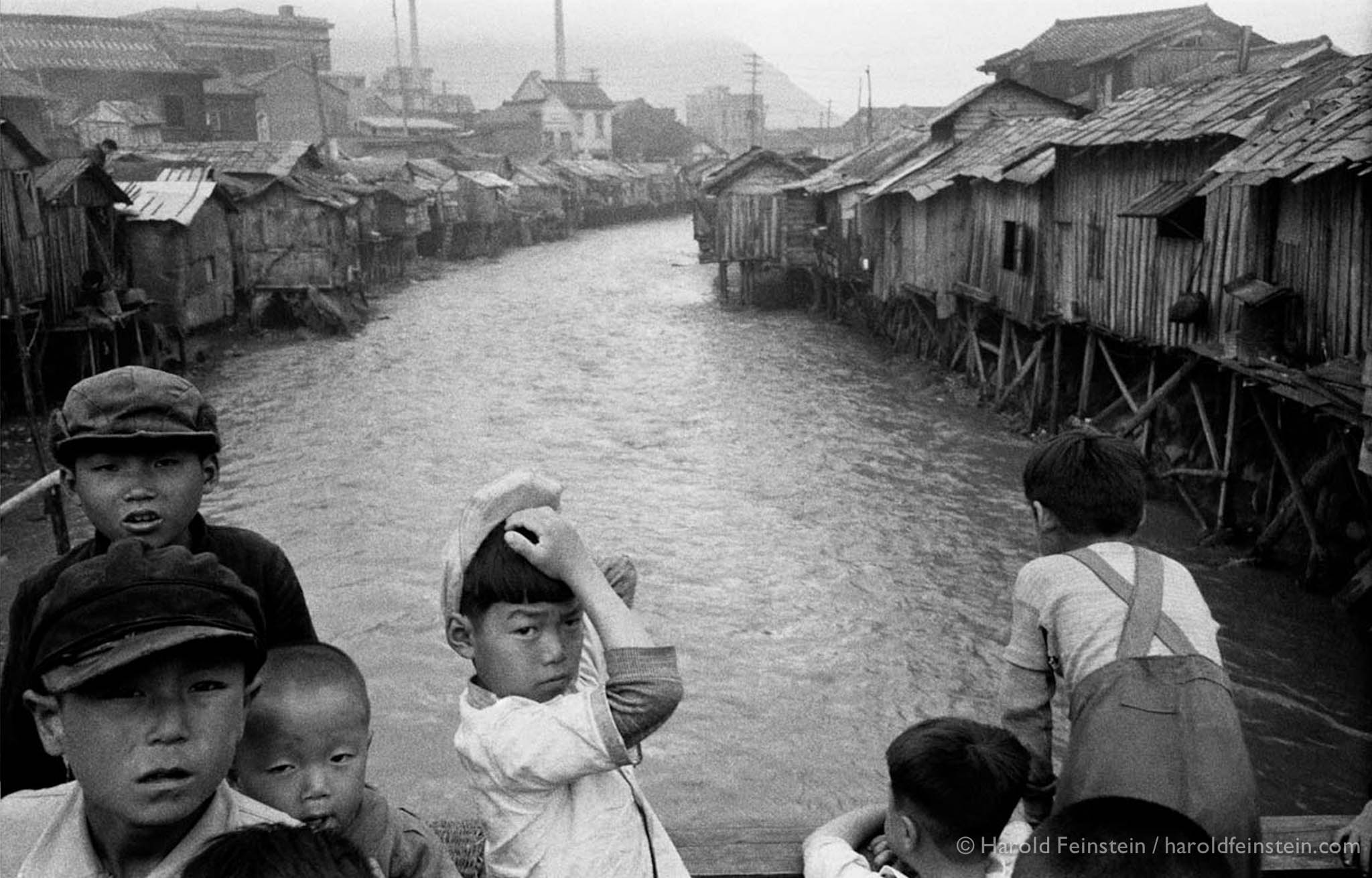

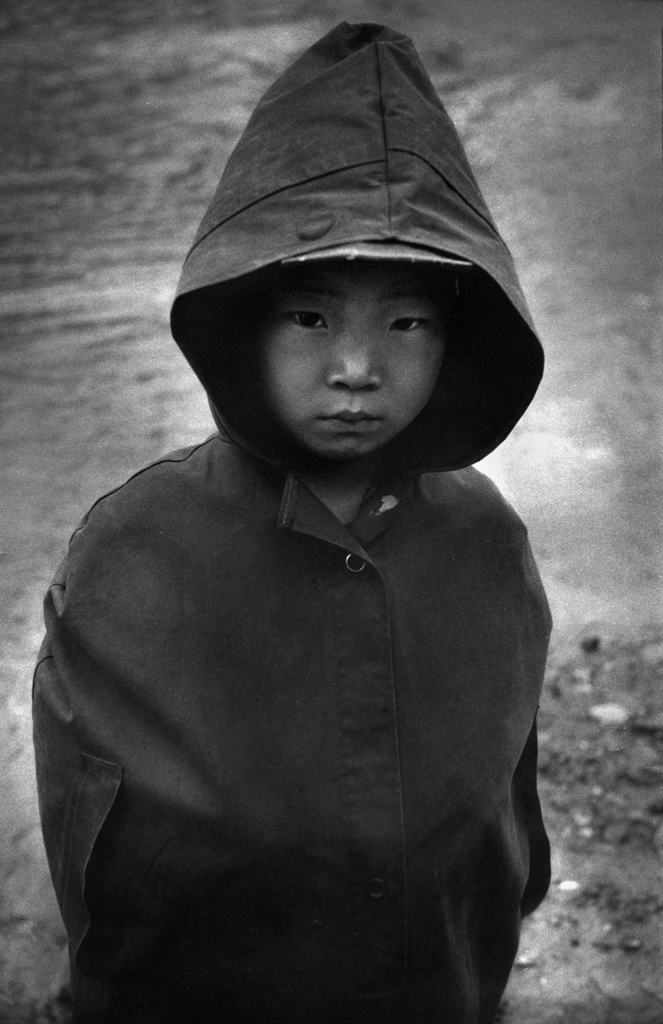

As a GI, I remember arriving in Pusan and receiving instructions not to “fraternize” with the local people. But, I confess that I broke that rule. I lived for awhile with a Korean woman in a small shack and got to know the local children. I also witnessed their sacrifices and suffering.

When the U.S. Congress created Veteran’s Day in 1926, it was resolved that this day would be commemorated “with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations…”

I don’t see much of that, but it is in that spirit that I have shared a few of my photos from my Korean War experience and remember, with great fondness and sympathies, those GIs who were conscripted with me and those civilians who I came to know. I respect them now as I did then.

One of your most moving blogs – respectful and loving toward all those whose lives have been touched by war while also being clear in understanding the personal and communal costs of that involvement. Both you images and words shine light on a dark and difficult subject. Thank you.

I agree with Barbara and wish this post could have appeared in the New York Times and be read into the Comgressional Record. The words and images are powerful complements.

I send thanks, too, Harold, especially for bringing the moral injury article to my attention.

Best,

Allan

Harold,

Lovely and insightful thoughts and images, as always. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” (William Faulkner). PTS (I agree about the “D”) manifests itself in as many ways as their are individuals. For each and every one it does demonstrate their sanity and their humanity.