Gene Smith, James Karales and me: Remembering the Pittsburgh Project

I want to recommend to my readers a terrific blog post recently published in The Paris Review written by Sam Stephenson. Entitled In the Darkroom with W. Eugene Smith, the blog shares some of the history of Gene’s passionate, and some would say obsessed, absorption in The Pittsburgh Project — an undertaking that Stephenson aptly calls “one of the most ambitious projects in the history of photography”. The post also shares the reminiscences of James Karales, who, fresh out of Ohio University and still wet behind the ears, landed a job as Gene’s darkroom assistant at a time when Gene was probably at his most manic and creative. I had to laugh at Sam’s commentary:

It was like asking a new film-school graduate to help Francis Ford Coppola complete Apocalypse Now, a project that almost killed the director and alienated everybody around him.

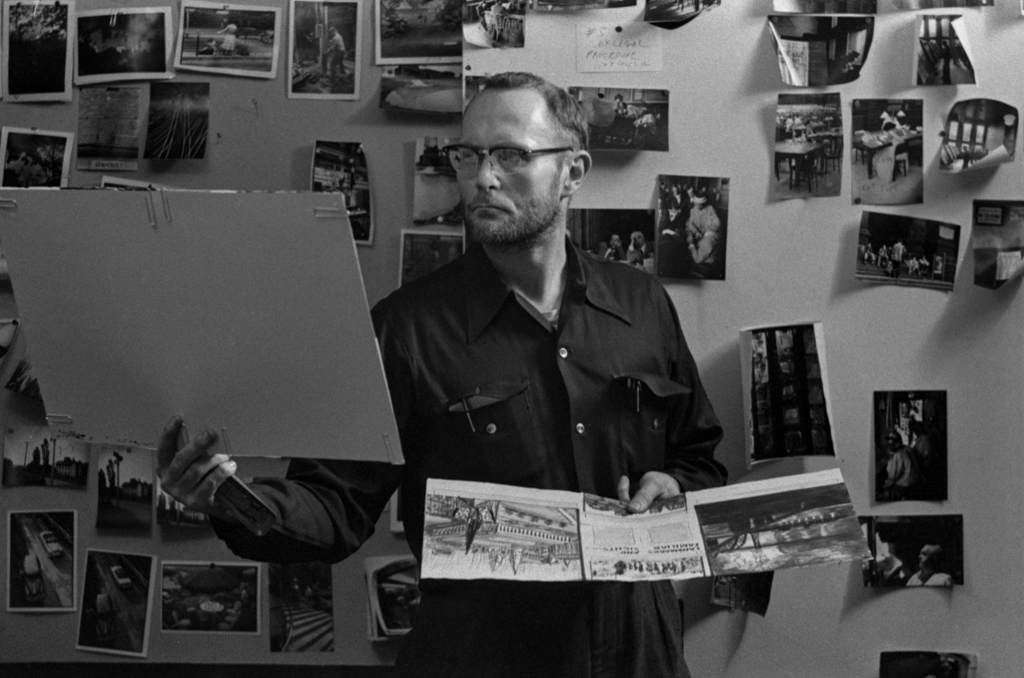

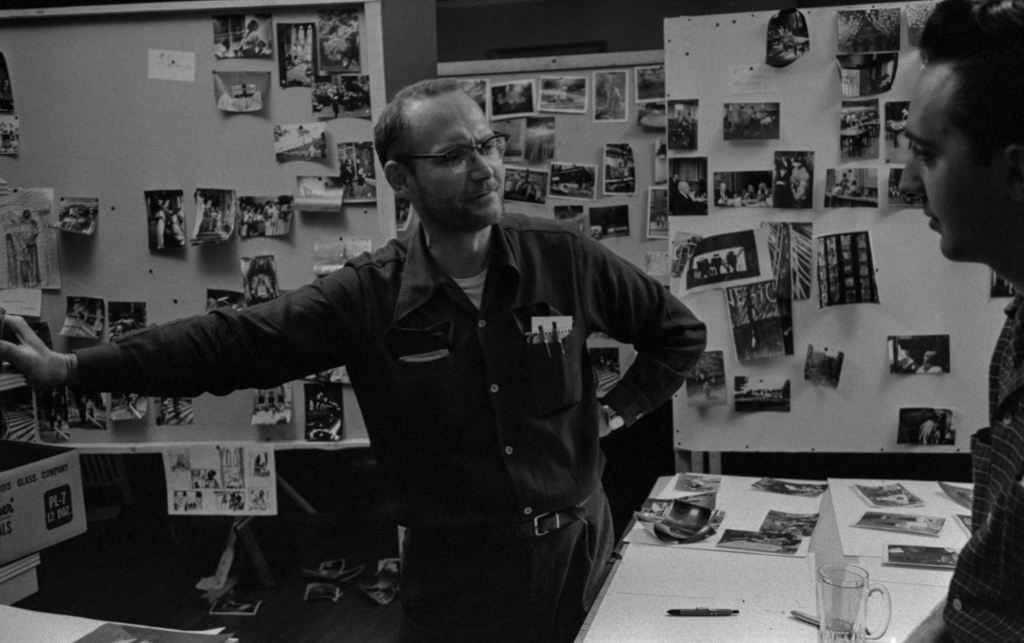

Sam’s blog inspired me to add my own recollections of working side by side with Gene and James at the time putting together the lay-out for the essay. Serendipitously, I just came across some old negatives from that period, which I forgot I had! They aren’t all great photographs, but worth sharing for historical purposes. (Yet another group of “lost and found” negatives! See my blog post on the negatives I recently found from a Photo League meeting).

Gene was one of the most important people in my life, and I’ve already written a number of blogs about our friendship and his influence on me (see below). I truly loved him and still miss him. By the time he was thick into the Pittsburgh Project, I was 26 and we had known each other for seven years. He asked me to come to Croton-on-Hudson and put together the lay-out for the Pittsburgh Project. Several years later, after the strain of the project had irrevocably broken his marriage, he left his wife, Carmen, and their four children to take over my space in 821 Sixth Avenue, now known as The Jazz Loft.

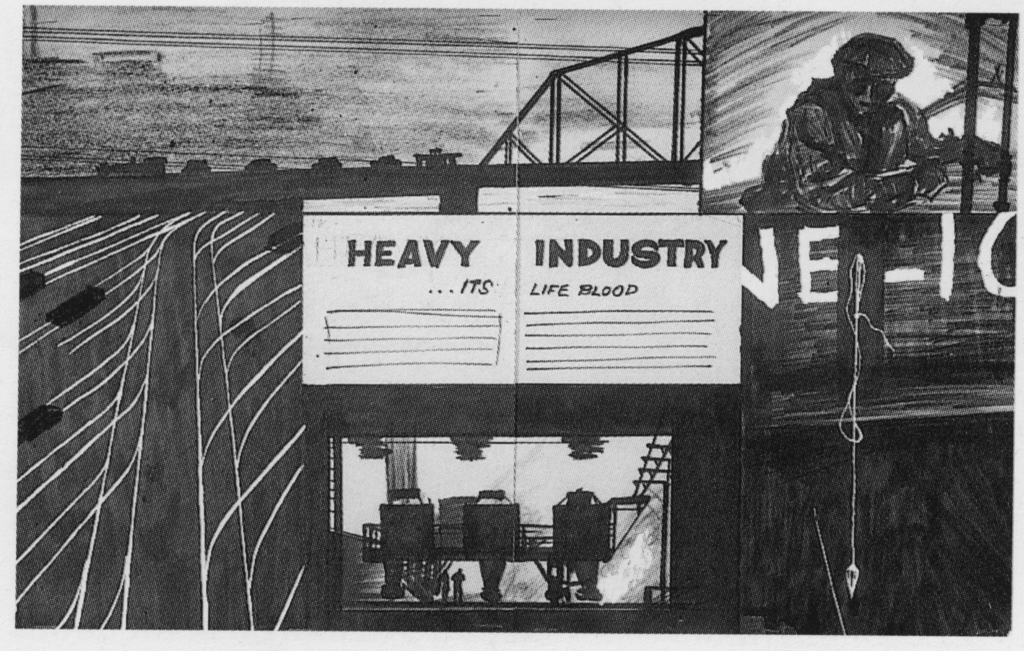

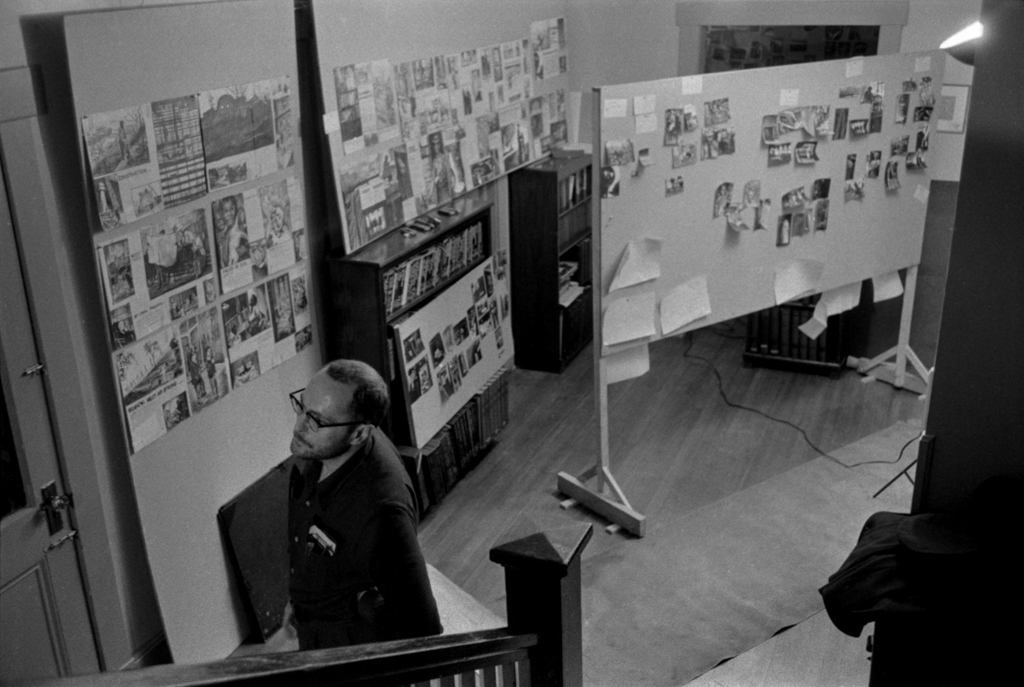

Sam’s blog describes beautifully the kind of creative chaos that surrounded the Pittsburgh Project, so I won’t go into too much detail here. Suffice it to say that in 1955, Gene had left a twelve year uneasy relationship with LIFE magazine and had joined Magnum. He received a commission from filmmaker Stefan Lorant, to take some photographs in Pittsburgh for a book celebrating the city’s bicentennial. The project was expected to take three weeks and result in 100 “scripted” photographs that could easily be dropped into a pre-packaged lay-out for the book. Three years and 21,000 negatives later Gene was deep in the throes of his own vision for this magnum opus, and had long since lost Lorant’s good will and trust. He was hoping for a large spread in LIFE instead. I came in to work with him on the lay-out in 1956, drawing mock-ups of an evolving spread meant to cover dozens of pages.

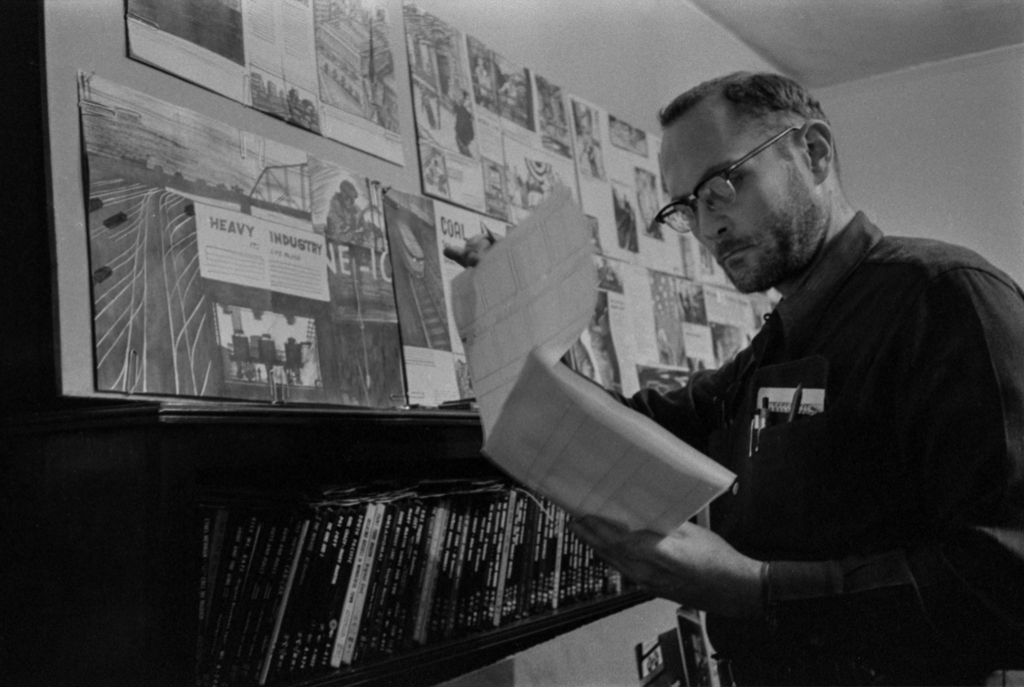

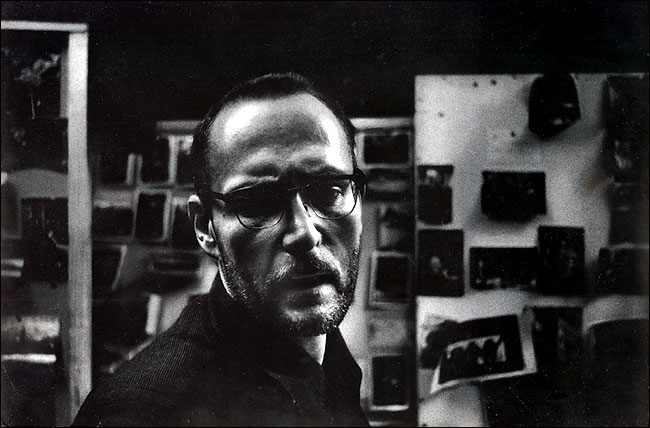

Using the old large format LIFE as a guide, Gene and I would discuss the choice of photographs, editing from hundreds of 5 x 7 proof prints he had pinned up all over his house on 4 x 8 mounted bulletin boards. Then we would put them in a potential sequence and I would go to work with pen and paper to produce the mock-ups.

Below is one of my drawings taken from Stephenson’s book Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project (Norton, 2001). The photograph beneath it shows the same piece on the wall among the array of other drawings from the lay-out.

As James worked in the darkroom producing proofs, I produced revisions of the lay-out and Gene scrutinized both. Lots of words describe this time — crazy, absorbed, chaotic, dark, manic, humorous. But, for me, the overall experience was one of joy. Regardless of Gene’s reputation among editors, and even some photographers, for being obsessive (which he was), and perfectionistic (which he was), he was a man of extraordinary genius and it was impossible to resist getting caught up in the creative excitement of working with him.

Alas, LIFE never did publish the work, which finally came out in Photography Annual 1959 in a much smaller format. Gene had been offered up to $20,000 for the essay by numerous publications, but his refusal to give up control of the edit and lay-out foreclosed those deals. Ultimately he got paid $1900 for a 38 page smaller format essay. He had complete control of both the edit and the lay-out, but at that point his vision for a larger, longer spread was impossible. He ended up calling the project a failure.

Sam’s blog mentions a few aspects of Gene’s approach to his work I’d like to underscore. Most photojournalists of that time were asked to do a shoot and provide a given number of photos, which would then be edited and layer-out by the editors. For Gene, control of the edit and lay-out were crucial parts of the creative process. He always looked at the whole picture, not the parts. As James explained it:

Gene believed you can have a picture that’s really powerful, but if it didn’t fit within the lay-out, in the storytelling situation, then you don’t use that picture.

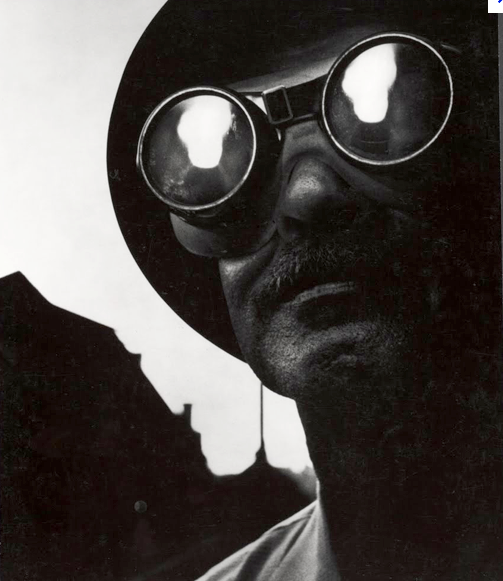

Secondly, Gene’s printmaking was legendary. As James pointed out, even Gene’s proof prints had to be perfectly printed, making the huge number of them he amassed over the years valuable works of art in themselves. Recently my wife, Judith, came across some interviews of me from many decades ago, and found this piece where I speak about Gene’s approach to life — and to the printmaking process. I couldn’t say it any better now:

Interestingly, the one photograph I took of him that became quite well-known, and was purchased by The Museum of Modern Art, is one that I printed very darkly — perhaps as a way to express who he was. Both of us were into using potassium ferricyanide liberally and in this print I printed it very deep and brought out the highlights with potassium ferricyanide. It seems to express the heroic qualities I saw in him!

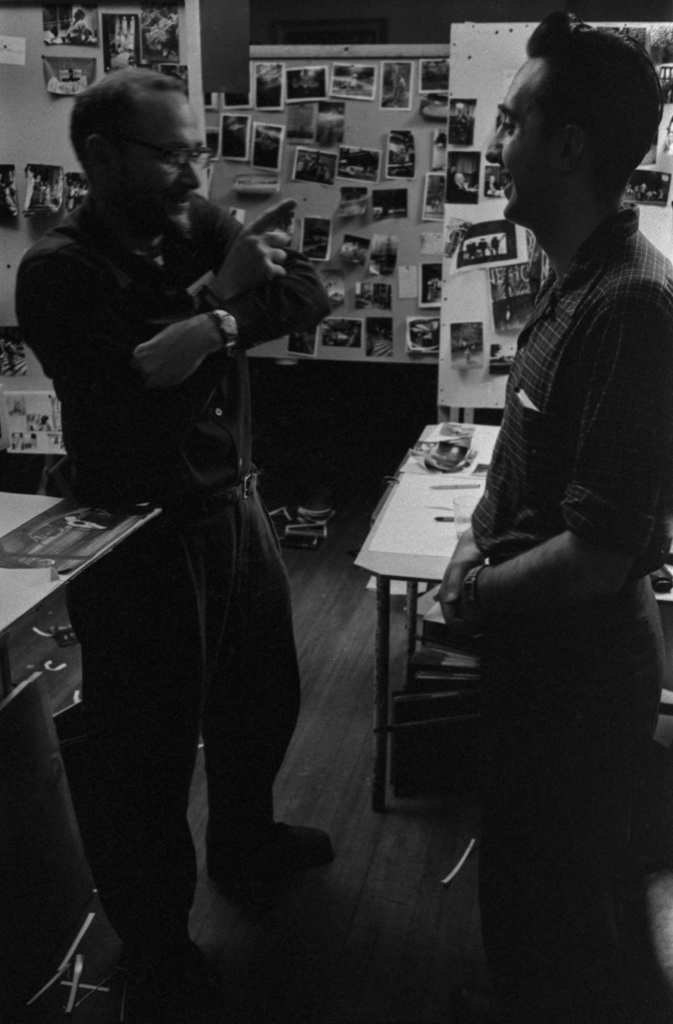

All was not dark and earnest during this time, and my own memories of this period of work are primarily about the many laughs we all had. James was a very sweet guy, light-hearted, patient and willing to put up with Gene’s demands. And Gene was extraordinarily generous to those he cared about. Below are a few photos of the lighter side of our time together.

The last time I saw James was in 2001 when the Carnegie Museum flew us both out to speak at the opening of the exhibition Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project, curated by Sam Stephenson. Sadly, he died in 2002. After the Pittsburgh Project he went on to become a brilliant photographer in his own right. Some of his work is now being exhibited at the Howard Greenberg Gallery until January 4th. If you’re in the neighborhood, you should definitely see it.

This is a great piece. Thank you for sharing.

Harold – Both your piece and the essay by Sam Stephenson provide a fascinating glimpse into the life and work of a key figure in the history of photography. Thank you for remembering and sharing!

Gene Smith has always been an inspiration, even if my work is in another direction.

Wonderful reflections. It reminds me of the realization, sometime in high school, when I was first starting to work in the darkroom, that Gene Smith had influenced my photography before I even really knew who he was. I had recollections of a couple of the Life essays from the time that I was in junior high [the 50’s] and still remembered the images what must have been [now that I was 14] half a lifetime later. I can still remember them now…Your essay helps add another dimension for me.

Thanks, so much.

Great read. I stumbled upon this because I blogged about the upcoming NYC show at PDNB in Dallas that you’re in and got a pingback comment from your website. I’d already linked to your PDNB bio but of course found so much more here. I love the information age we’re in where something about everything is accessible with minimal effort and much of it is pure happenstance. It’s killing my industry rapidly but there’ll always be a need for strong photojournalism regardless of how it’s disseminated. I have the Pittsburgh Project book and have marveled at it and the extraordinary… Read more »