What to remember: Reflections on Memorial Day 2021

Unquestionably war has touched us all. Every single person, no matter who they are or where they live, has been touched by war. Scars from the traumas of war are passed down throughout generations and layered with new scars as the self-perpetuating cycles of war and violence continue to be fueled partly by the unhealed wounds from former wars. War is one of the great fulcrums that shape civilization’s evolution, together, thank goodness, with all the better angels of our nature that valiantly aim their gaze at the higher ground of a future beyond war. May it be so.

Today is a day to remember veterans and I want to begin this post with a tribute to those within my own family who went to war, either by choice or draft, then turn to Harold’s war photography, and finally end with a short reflection on selective remembering and forgetting, and the consequences of both.

I want to remember and celebrate my beloved uncle, Edward P. Thompson, my father’s brother and a true war hero. He was a rifleman in the infantry in WWII, which, as my cousin Marty Arnold explained to me, means he really was on the front lines. Unlike machine guns, rifles have a much shorter range, so in order to target and shoot you needed to be in very close proximity to the enemy.

Not long after arriving in Belgium, he and another buddy were engaged in a skirmish in a recently plowed field. His best friend, Herb Rosier, was pinned down, shot in the stomach, and crying for help. Ed crawled on his hands and knees to retrieve his friend, pulling him “inch by inch” back toward their platoon, until finally he could pull no more. At this point, Herb had sustained several more bullet wounds, and Ed could feel bullets hitting his own backpack. At one point when he no longer had the strength to pull his buddy he stopped, exhausted, and called out for more help. Just as he had given up hope, another guy from the platoon ran out and rescued them. This man was someone Ed was convinced would never risk his life for another, and from that moment forward he became much more mindful about judging others. Several days later Herb died. Later Ed would be engaged in some of the fiercest fighting of the war including the Battle of Bulge (northern perimeter).

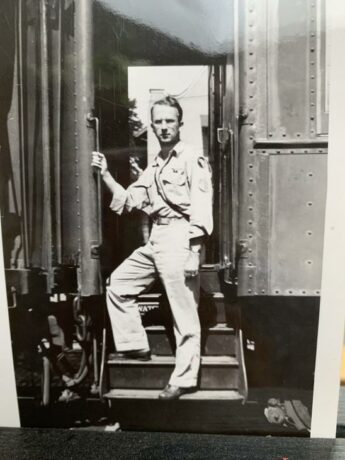

After the war ended in Europe, he returned home, but was quickly shipped off to California to be deployed to Japan — a campaign he knew would be a suicide mission. He recounts it as the only time he ever considered suicide. On the train headed west a couple of girls, noticing how subdued the soldiers were, announced: “Hey, haven’t you heard?! Japan surrendered. The war’s over!” He was saved.

We are blessed that his life was spared. He went on to be one of the pillars of his community of Kalamazoo, Michigan; an attorney, a leader in the “battle” to desegregate the local school system (and it was a battle), a loving husband, father, brother, uncle, and grandfather.

While he received a Bronze Star in the war, and later a purple heart for an injury, he carried trauma with him for the rest of his life. His PTSD wasn’t obvious to most people, but later in life, his memories haunted him. My last time seeing him, in the mid-stages of Alzheimer’s, his war experiences were alive and kicking to get out from within his psyche and one could only bear witness to the memories — like still photographs — surfacing at last from the now-unlocked box in his mind, where they had been stored until the end. I pay tribute to this incredible man, a true hero and inspiration. (Thank you to cousins, Shirley Thompson and Marty Arnold for helping me with the details of this story.)

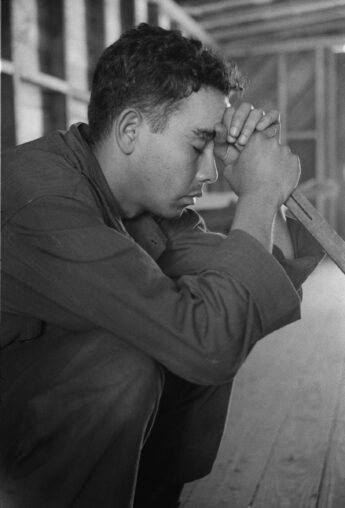

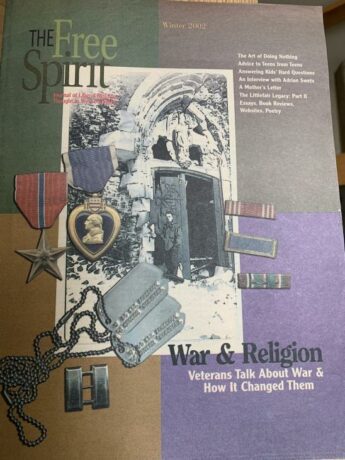

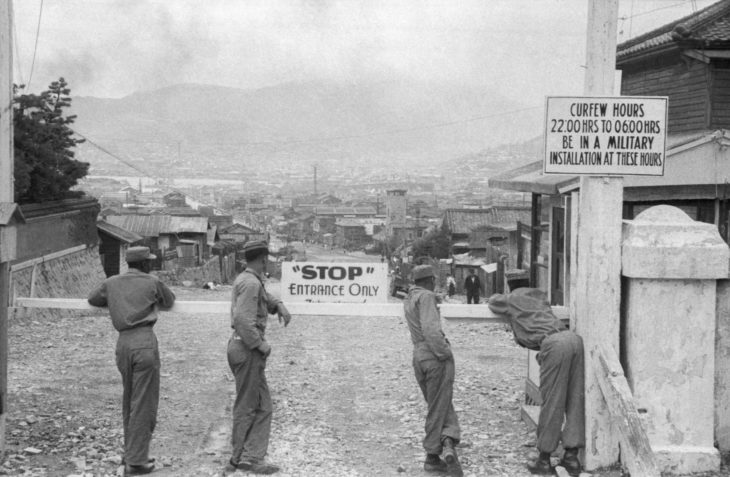

Harold had hoped to be assigned as a photographer, but was put in the infantry instead. This ended up being a blessing in disguise as he was able to carry his camera with him wherever he went. His Army Draftee series shows the everyday experiences of draftees as they prepared to go to war — from the draft board meetings to basic training, to being shipped out, disembarking in Pusan and preparing to head to the front. Due to a non-combat related injury Harold was fortunate to be spared the worst of the horrors and was sent back from the front to headquarters to paint signs and serve at the pleasure of his commanding officers. But it was during this time that he turned his attention to documenting village life in are around Pusan even though his commanding officers asked the GIs not to fraternize with the locals. Harold was always a rule-breaker. Eventually he lived with a Korean woman and became a friendly face among the populace.

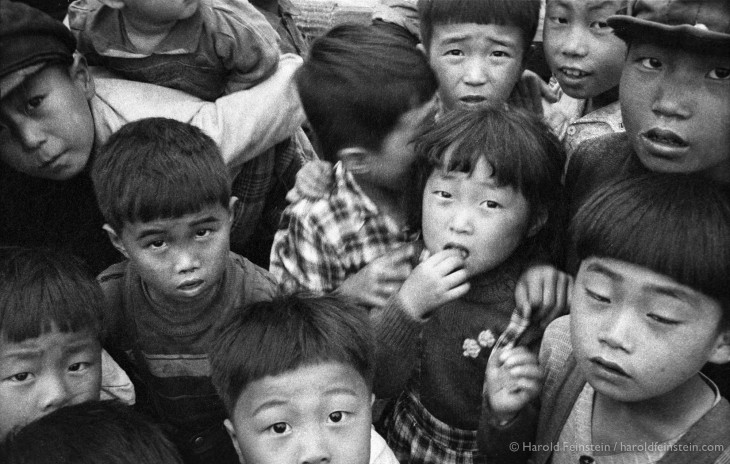

His photographs of Korean men, women and children remind us to remember the civilians, especially children, from all sides of conflict who are caught in the net of warfare. Civilian casualties in modern warfare outnumber military deaths.

The past few months we’ve been doing a good bit of scanning in the studio, particularly negs from the Army series. In most cases they were already marked by Harold, but had never made it to the front of the line for scanning and printing before he died. It’s been an exciting process, and I’m going to share more of these never-seen photographs soon in a future post. Among the really interesting, and I think historic, discoveries are a series of photographs of the civilian demonstrations that took place in Pusan as the July 1953 Armistice Agreement approached. Much of the population opposed the separation and occupation of the country and hoped to battle on to reunite their country. The brief slide show below shares some of these historic photos. Others are still being scanned.

A final reflection on this Memorial Day. I ponder the narratives carried in our collective psyches about war, glory, sacrifice, national pride, and the selectivity of memory. Who is remembered and who is not? And why?

To this last point, today, May 31st, is also the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre — the day a white mob began a two day rampage through Tulsa’s Greenwood district, also known as Black Wall Street — a 35 block area, burning every home, and destroying the neighborhood’s vital businesses. Historians estimate that up to 300 people were brutally murdered by the mob, who had been coached by local police. Over 10,000 were left homeless. And now, with 100 years behind us, and six days from the one year anniversary of George Floyd’s murder the question comes to my mind, how do we decide which “wars” to commemorate… and why?

Consider that one definition of “war” from the Oxford dictionary: a sustained effort to deal with or end a particular unpleasant or undesirable situation or condition.

Stunningly, this excerpt from the prose poem “Recipe for a Massacre: Tulsa, 1921” by Quraysh Ali Lansana sounds like it could be from the battlefields of Korea, or Afghanistan.

“…. a deputizing of hundreds. a machine gun on standpipe hill. a dropping of bombs from chartered planes. a burning. little africa on fire. a marching at gunpoint. three internment camps. three-hundred dead in the ruins of their own prosperity.”

Machine guns, bombs, burned homes, internment camps? Some wars aren’t called war. After almost a century of non-acknowledgement (did you ever read about it in your history books?), a new museum, Greenwood Rising, will open this summer. It bears the words of James Baldwin:

“Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

For more of Harold’s Army Draftee series, this clip from the film Last Stop Coney Island shares more great photography. Wishing you all a close and memorable time with your family today.