Prints and printmaking, Part 1: Silver gelatin vintage, printed later and modern prints; what’s the difference?

When I first began getting involved with Harold’s work, during and after a long career of my own (completely unrelated to photography or the art world), I found myself a complete novice at the bottom end of the learning curve. Among the many things to decipher and digest was the question of what constitutes a vintage print, a modern editioned print and the in-between designation of “printed later” prints. The definitions seemed paradoxical — and still do. Could it be true that an image captured as a film negative in 1987 and printed that same year could be worth more — or priced higher — than a negative created in 1951 and printed in the early 70’s? That simply didn’t (and doesn’t) make sense! But one is considered vintage and the other isn’t — and generally speaking a “vintage” print is worth more. Thinking that others who have inherited or are managing a photographic estate might find themselves falling into the same puzzling “huh?”, I thought I’d share what I’ve learned so far. Many questions still remain!

I found a good primer for understanding the basics at this panel discussion held recently during Photo London. The event, moderated by Brandei Este, Sotheby’s head of photographs and sponsored by Citi Private Bank included Michael Benson, the co-founding Director of Photo London, Brett Rogers, Director of the Photographer’s Gallery, Giles Huxley-Parlour, Director of the Huxley-Parlour Gallery and Carrie Scott, of Carrie Scott and Partners, an independent curator and dealer who represents Harold’s work and had produced the remarkable exhibition Found during Photo London.

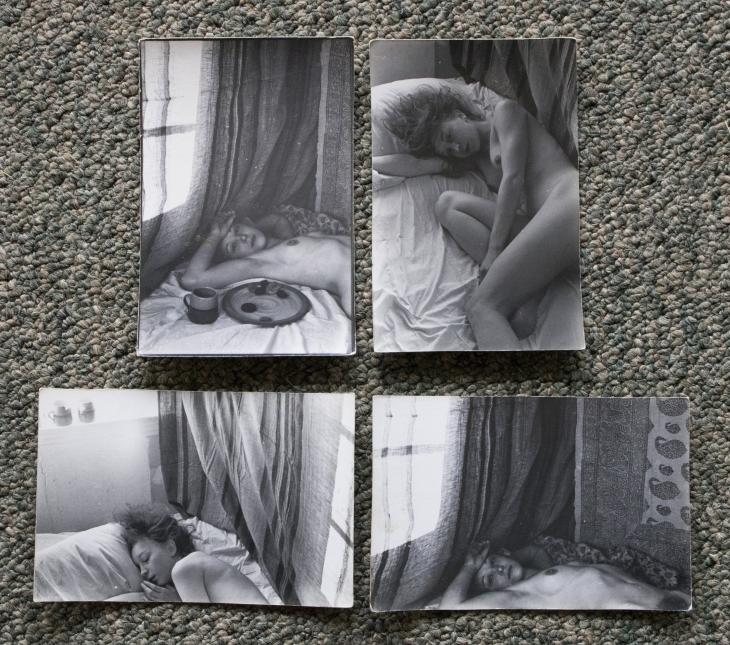

At one point in the conversation, Carrie spoke about the mix of old and new prints hanging at the show referring to the “aura” of the old prints printed by Harold. This led into a deeper exploration of the designations “vintage”, “printed later” and “modern” prints. It was Giles Huxley-Parlour who went into more detail on this and I recommend those interested to listen to the whole passage from the video inside the article mentioned above (starting at 33:13 through 40.:00) In fact the entire panel discussion is super for the collector and photographer alike. Here are a few points he makes:

- First and foremost, people collect photographs because they are art objects. That means, that while the image itself is a beautiful capture of a moment, it is the the print from the negative (or digital file) that becomes an art object. It’s age, condition and and tonality — in short, it’s “aura” is part of what the buyer is buying. For many collectors, older is more desirable, even though you and I might actually like the rendering of a “modern” print better.

- While there is no absolute consensus, a vintage silver gelatin print is one that is made within a specific narrow time frame close to when the negative was produced. Should it be printed within the first year, up to 5 years out or even more? This is where dealers seem to differ. I know one person managing an archive of a very well-known photographer from the early 20th century who considers 10 years the window of time permissible to use the term “vintage”. The further back you go in time, the more meaningful the term “vintage” becomes, since at some point, the collector is buying a true antique.

- The next tier in the hierarchy are prints designated as “printed later.” In his explanation Giles refers to Cartier-Bresson prints made in the 80’s or 9o’s from the original negatives. These are referred to as “printed later” prints and constitute the majority of older silver gelatin prints in the market today. This is certainly true for Harold who printed throughout his lifetime, but had particular periods where he took the negatives of his most iconic images and did marathon sessions in darkroom in the 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s making multiple prints from the 40’s and 50’s. These “printed later” prints are beautiful, many printed as 11×14 on Agfa’s legendary Rapid Portriga paper which produced warm, rich blacks. Many photographers were disappointed when they could no longer get this paper!

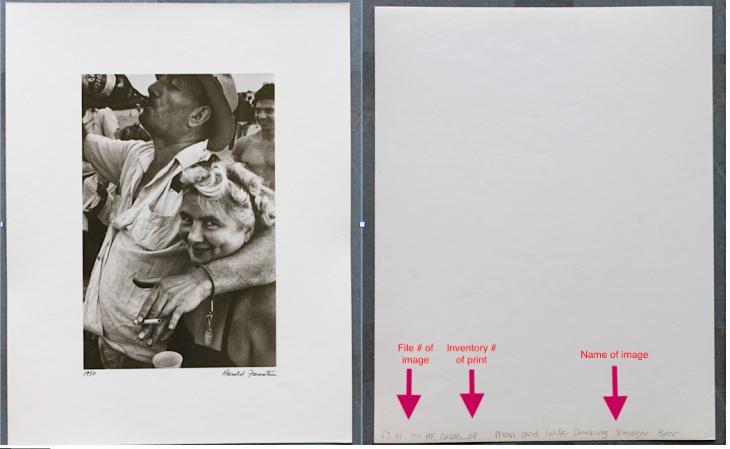

- Finally, the third category of prints are called “modern” or “contemporary” because they have been printed “recently”. Obviously recently is a relative term and today’s “modern” prints will be considered “printed later” in a decade or two. In the case of Harold’s work, only the “modern” prints were printed as editions, since the trend toward editioning work did not begin until the late 80’s, when the photography market began to seriously develop. Prior to that photographers had been printing as needed.

A closer look: The ironies and paradoxes of the print as art object

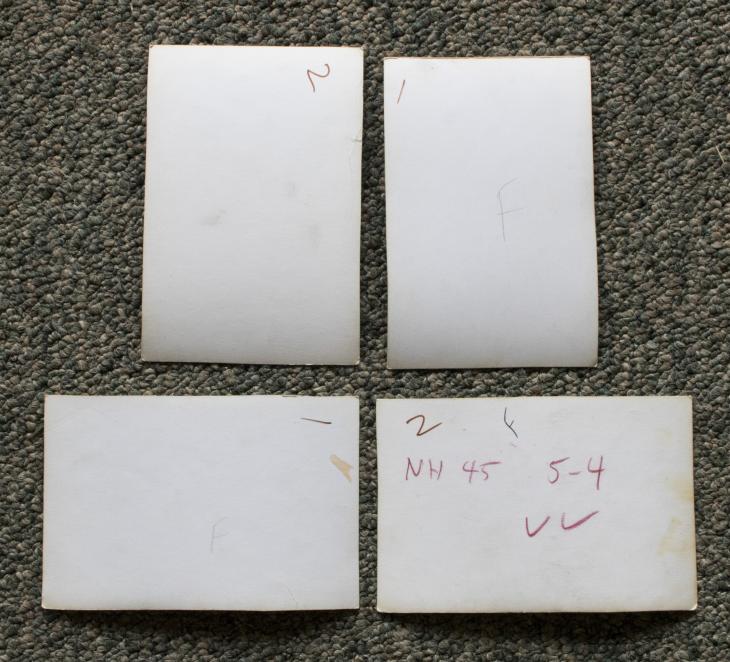

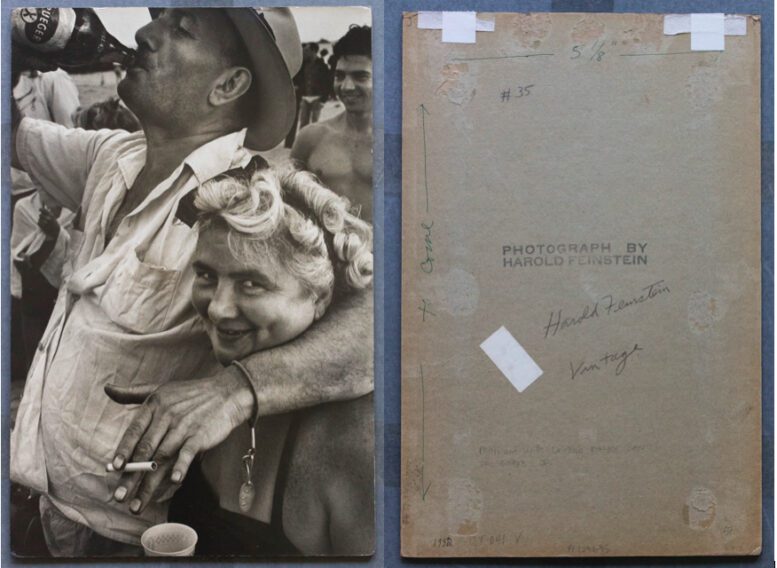

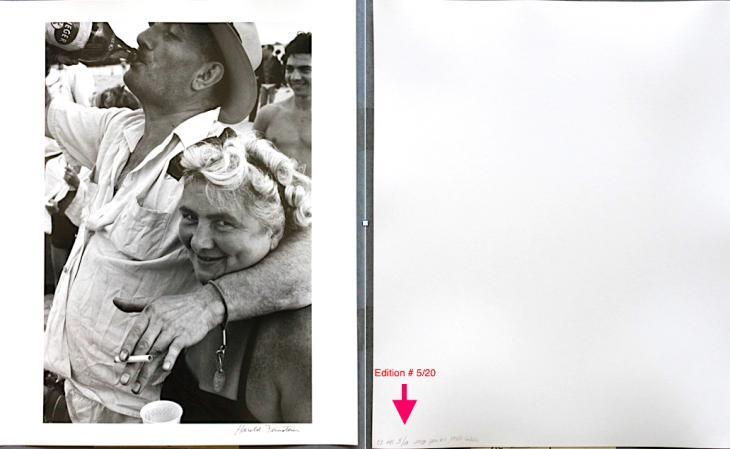

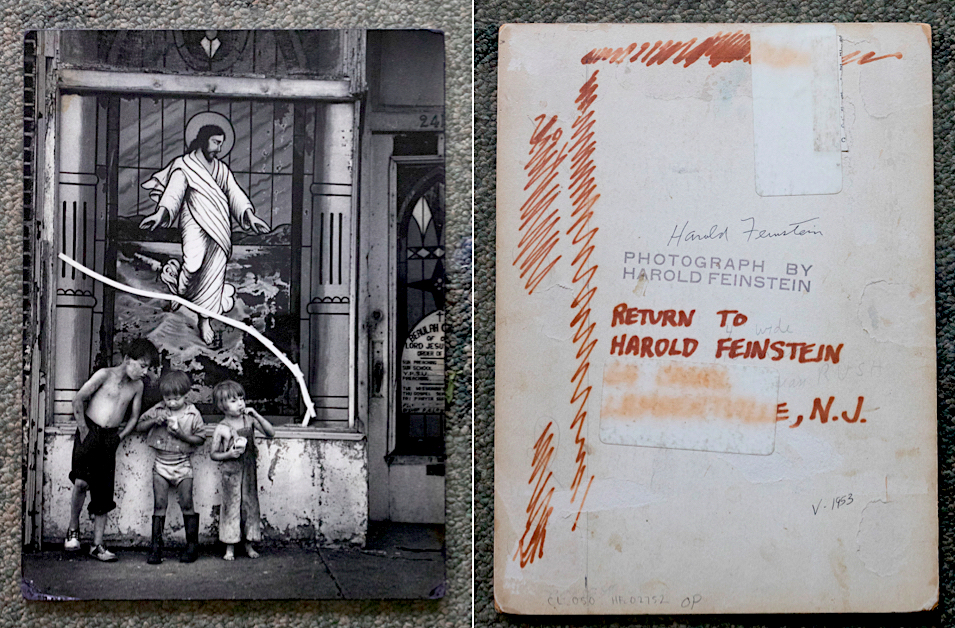

As Giles points out in his explanation, vintage prints made in Harold’s day and well before were generally never made to be exhibited. Rather they were working prints made for publication for magazines and newspapers.

“It’s a miracle really that they’re still here, because they used to be chucked away. These are working historical objects. They’ve got stamps on the back, lines on the them, all kinds of marks. As a connoisseur collector you can get really excited about them. Look at the object. You can really enjoy the thing. They have a huge premium for the right collector.” Giles Huxley-Parlour, Director Huxley-Parlour Gallery.

Furthermore, vintage prints are expected to have flaws. When Brandei Estes asked Carrie Scott about the condition of Harold’s old prints, Carrie stated that she had an expert come in to evaluate them and they were defined as “good”. And…”there are a few flaws here and there.” To which Brandei replied:

“Old prints should have flaws. Prior to being here at Sothebys, I worked for eleven years in galleries. If you saw a vintage print in perfect condition, alarm bells go off. ” Brandei Estes, Head of Photography at Sotheby’s.

These comments helped me as a manager of Harold’s archive to appreciate certain things I hadn’t understood before. Firstly, oh how I wish there were more vintage pieces! But the truth is, as stated above, Harold made working prints for magazines. When he had exhibitions in the 50’s he would create a set for the museum of gallery — some of which I have, but many I don’t! Operating in those days as the typical “starving artist” he didn’t hold on to whatever print inventory he had for “posterity”, but sold the prints as a way to put food on the table! (I hope whoever bought those back then understand their value now!)

That said, he and many of his contemporaries, saw the print as an interpretive tool and one more way to express the artist’s vision. (To be covered in the next blogpost).

Finally, when it comes to contemporary prints, as pointed out in the article A History of Limited Edition Photography by David Walker in this edition of PDN: The Business of Fine-Art Print Sales (which has an number of other worthwhile articles for photographers to consider), while the initial thrust of editoning had been to produce scarcity and drive up prices, it has often not produced that effect.

“The typical edition was 50 to 100” prints at that time, says dealer Alex Novak. Ironically, the practice of issuing limited editions increased the supply of photographic prints, notes Stephen Perloff, editor of The Photo Review. Photographers used to print as needed, usually only a few images at a time, he explains. Once they started printing entire editions, a lot of prints got made, but many never sold.”

When the trend toward creating editions began, photographers created edition sizes of 50 or 100. Nowadays the number is generally much smaller. When Harold began creating editions in the mid 2000s, the size was declared at 20, but in most cases only 10 or 5 of each image were ever printed. (In that language of editions, the terminology is “realized” – e.g. only 10 were ever “realized”). In his case, it was a good idea to create editions since it offered him the opportunity print imagery never before printed, leaving behind a broader selection of imagery and signed prints from which collectors can choose.

One last inconsistency pointed out by Giles on the Sotheby’s panel was illustrated by the story of Ansel Adam’s prints. In his case, the printed later prints actually sell for more than the vintage ones. As he put it: “Most people don’t want the little brown square — they want a great big epic. So, it’s not always the rule that vintage are more expensive.” I’m supposing this is particularly true for the kinds of huge landscapes for which Adams is known.

Finally, when I had a discussion with gallerist Howard Greenberg of the Howard Greenberg Gallery shortly after Harold died about the photography market’s fetish with vintage prints, as opposed to let’s say, “old prints” (giving my example of the 1987 negative and print made the same year versus the image captured in 1948 and printed in 1975), his comment was to forget the language of “vintage” vs. “printed later” and just ask the question: is it an old print and a beautiful print? That seems to make perfect sense to me! (Remembering that today’s contemporary print will someday be an old print!)