Bio

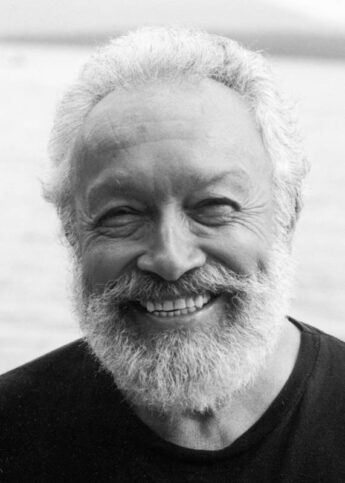

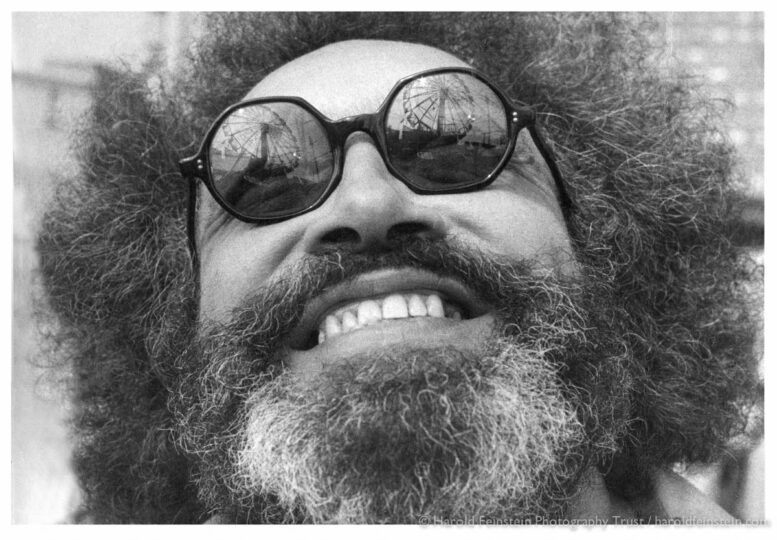

Harold Feinstein was born in Coney Island, New York, in 1931 to Jewish immigrant parents. When he was 15, he borrowed a Rolleiflex from a neighbor and began photographing Coney Island and the streets of Brooklyn. He never stopped.

By 16 he had dropped out of school, got a room at the YMCA and began to devote himself full-time to photography. In 1948, at the age of 17, he became the youngest member of the historic Photo League and by the age of 19, Edward Steichen, director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, had become an early supporter and purchased Harold’s work for the museum’s permanent collection. According to photography critic, A.D. Coleman, Feinstein “was considered by the photo world as something of a child prodigy.” When he died in June 2015, the New York Times declared him “one of the most accomplished recorders of the American experience.”

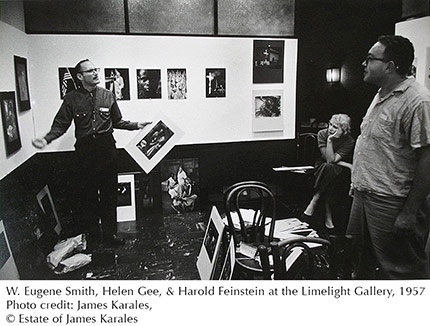

In 1952, Feinstein was drafted to serve in the Korean war as an army infantryman and continued to document daily life with his fellow GIs. Upon returning to New York he had his first exhibit in 1954 as part of a group show at The Whitney Museum, followed by a group show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and later solo shows at the George Eastman House (1957) and Helen Gee’s Limelight gallery (1958). In reviewing the Limelight Gallery show, New York Times photo writer, Jacob Deschin, called his work “the new pictorialism, the refinement of the craft as technically perfected language.” In 1958, H.M. Kinzer, editor of Photography Annual, declared a Feinstein print sale and show

“the most remarkable sale in the history of contemporary photography… [A]t the age of 26, Harold Feinstein has reached the point in his photographic career when the word ‘master’ is being applied to his prints by some ordinarily cautious critics.”

Throughout the 50s, Feinstein was a part of the bohemian ferment in the New York City art scene. After returning from the Korean War in 1954, he became one of the first inhabitants of New York’s legendary Jazz Loft. During that time he designed covers for the jazz label Blue Note records along with Andy Warhol and Reid Miles. In 1957 he was invited to join Jean Paul Satre and Samuel Beckett in launching the first issue of the controversial literary journal, Evergreen Review.

Feinstein was introduced to W. Eugene Smith in the early 50s and the two became close friends and collaborators. Smith asked him to create the layout for his monumental Pittsburgh Project, and in 1957 he took over Harold’s spot in the Jazz Loft when Harold moved out in order to make space for the birth of his first child. He said of Feinstein:

“He is one of the few photographers I have known, or been influenced by, with the ability to reveal the familiar to me in a beautifully new, in a strong and honest way.”

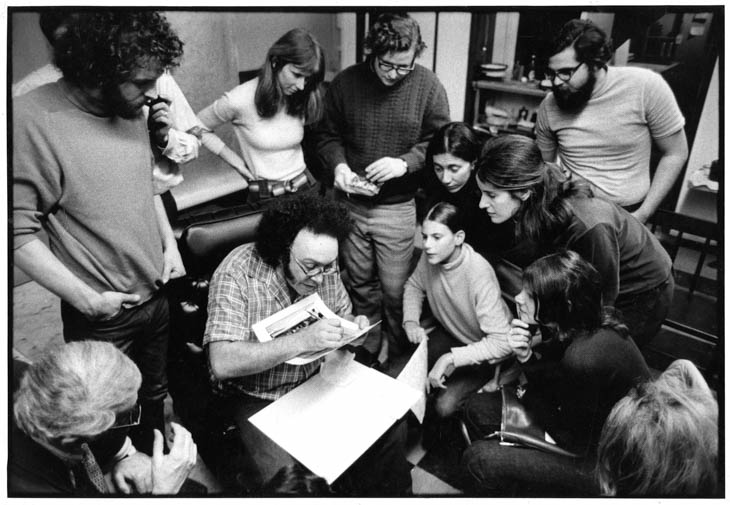

“a true teaching artist…one of a small handful of master teachers whose legendary private workshops proved instrumental in shaping the vision of hundreds of aspiring photographers.”

Among his students were Mary Ellen Mark, Ken Heyman, Louis Draper, Herb Randall, Mariette Pathy Allen, Lori Grinker, Wendy Watriss, and many others.

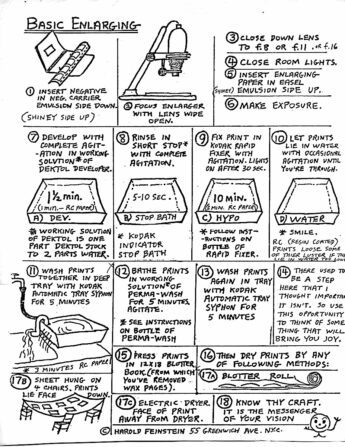

Throughout his life he was an iconoclast, experimenter and innovator, often breaking prevailing rules and forging new ground. Photography magazines frequently called upon him to write articles about his methods of printing, composition and shooting. As a master printer, he sometimes took liberties to get the image he wanted by using the bleaching agent potassium ferricyanide for dramatic effect, or by creating photomontages – practices that were frowned upon at the time. In the words of curator Phillip Prodger,

Feinstein was “part artist, part guru, part force of nature…His iconoclasm, individuality, and creative mischief meant that his most original contributions occurred outside easily defined circles of influence.”

Rarely did Feinstein regret his iconoclastic tendencies, with one exception. In 1955, Edward Steichen asked him to contribute seven photographs to The Family of Man, undoubtedly the most famous and successful photography exhibition in history. Feinstein declined the invitation, believing then that the photograph ought to be valued on its own as art and not because it fit into a theme. According to some photo historians, his decision, which he later regretted, may be one reason he was not better known later in his life.

Feinstein amassed a huge body of work over his nearly 70-year career. He is best known for his six-decade love affair with his home turf Coney Island. A review of his exhibition, A Coney Island of the Heart, at the International Center for Photography in 1990, said:

“Here is New York small camera school at its best; humanistic, engaging, almost intrusive… [T]his is the work of a man who loves people, takes unalloyed pleasure in seeing them enjoy themselves, likes to get close to them – and, by rendering their physicality in tactile, nuanced prints, enmeshes the viewer in the sensual, material world his ‘subjects’ occupy.”

While his Coney Island work has been much celebrated, his breadth is far greater. His oeuvre includes a large collection of classic street photography, nudes, portraits, nature and still life. His photographs from the Korean War offer an intimate look at the daily life of draftees from basic training to the front lines.

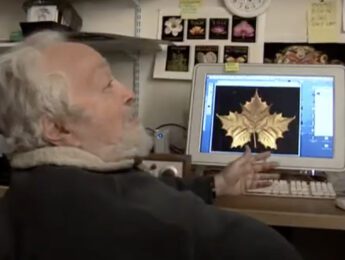

In addition to his classic black and white work, he devoted nearly two decades to color photography, both film and digital. In 2000, he received the Computer World Smithsonian Award for his breakthrough work in scanography, utilizing the scanner as a camera to produce breath-taking, highly detailed photographs of botanicals, seashells and butterflies. This resulted in seven books published by Little Brown Inc., and a sudden influx of licensing opportunities.

In nominating Feintstein for the award, the folks at the Epson Corporation described his book One Hundred Flowers, now in it’s third printing, as “an Audobon-like volume of flower images produced exclusively with digital techniques demonstrating a degree of artistic control over the color process that is revolutionizing the possibilities of color photography.”

The worldwide popularity of this new series prompted Britain’s newpaper, The Independent, to declare:

“In the realm of photography, Feinstein is what Beckham is to football or J.K. Rowling is to books.

His color work also includes 35mm street photography from the 1980s and a series he called Metropolis — New York architecture shot with a prismatic lens. New York Magazine called it “cubism verité” reminiscent of Georgia O’Keefe sculptures.

After the enormous success of his scanography series, which introduced him to a whole new audience of people unfamiliar with his earlier work, Feinstein was gratified to witness a renaissance of his early black and white work during the last decade of his life. In 2011, the Griffin Museum of Photography presented him with the Living Legend award. His first black and white monograph, Harold Feinstein: A Retrospective (Nazraeli, 2012) won a PDN (Photo District News) Annual Award in 2013 in the Best Photo Book category. In the past decade, exhibitions in the U.S., Europe, the Middle East, Russia and China have continued to stimulate new interest in his long career, and an international touring museum retrospective is now in the planning stages.

A documentary about his life and work, Last Stop Coney Island: The Life and Photography of Harold Feinstein premiered at DOC NYC in 2018 to a sold out crowd and a great review in the Hollywood Reporter. It has been garnering critical acclaim at film festivals in Europe, Australia, Canada and the U.S. and now streams on the Sundance Channel in North America.

After his death in 2015, his wife, Judith Thompson, took over the daily activities of the Trust and the management of the Harold Feinstein Archive, continuing to work with collaborators on exhibitions, publications and consolidation of the archive. Recent support from the Leonian Foundation coupled with funding from a Contribute.to campaign, is providing the resources to digitize, edit and package his hundreds of hours of audio, video and written materials from his teaching archive.

Feinstein’s work is represented internationally and collections are owned by The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The International Center for Photography, The George Eastman House, The Museum of the City of New York, The Jewish Museum in New York, and over two dozen other museums and corporate collections.